Previous state

The Charleroi Canal marks the western side of Pentagone, the formerly walled historic centre of Brussels. For all the centrality of the site, few bridges cross the canal and are located more than seven hundred metres apart. Hence the watercourse of about fifty metres across has become a socio-spatial barrier between two very different cities. A district rich in tourist attractions, monuments, expensive boutiques, pedestrian zones and impressive real estate extends from the south-eastern bank, while the opposite bank marks the municipal boundaries of Sint-Jans-Molenbeek and Laeken, an amalgam of poor, stigmatised neighbourhoods with large immigrant populations and not exempt of social conflict.

For decades, the industries located on this bank have been moving to the larger and distant spaces of the periphery, leaving behind run-down, abandoned factories. In recent years this industrial landscape has been undergoing a process of transformation in which many of the old factory sites have been renovated as venues for new activities. The “Tour & Taxis” complex, which now houses book and antique fairs, a design market and big music festivals, is one example. The regeneration of the sector is encouraging the spread of the cultural and third-sector activities of the old centre across the canal and into spaces of the opposite bank. Nevertheless, the apparent improvement also runs the risk of initiating a process of gentrification. As has happened in other European cities since the 1980s, the increasing number of attractive features in the zone could bring about higher rents and the expulsion of lower-income residents and small-scale businesses.

Aim of the intervention

Given this danger, the “Platform Kanal” was founded in 2008 as a citizens’ non-profit initiative concerned with encouraging reflection and debate about the challenges and opportunities entailed in the transformation of this sector. Starting in 2012, the Platform decided to hold the “Festival Kanal” every two years, in the summer, with a view to filling the area with temporary activities in order to call for a strategy of urban improvement which, apart from forestalling gentrification, would be truly inclusive.

In 2014, the organisers commissioned the architect Gijs Van Vaerenbergh to design the main stage for the second “Festival Kanal”. However, Van Vaerenbergh made a counterproposal which, while it may have been less practical, was certainly highly symbolic and in tune with the basic aims of the Festival. His idea was to use the budget set aside for the stage—approximately €50,000—to build a different kind of temporary structure that could connect, even if only for a short time, the two banks of the canal.

Description

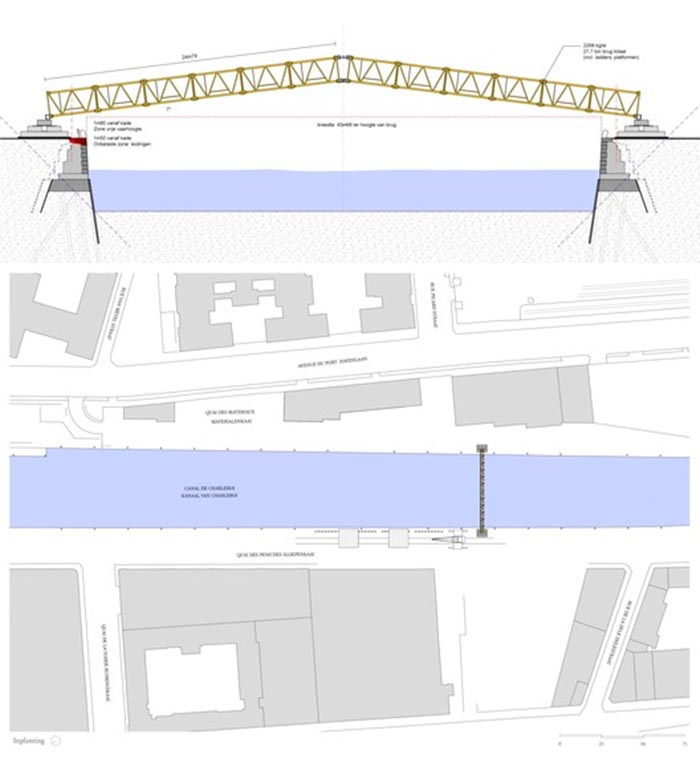

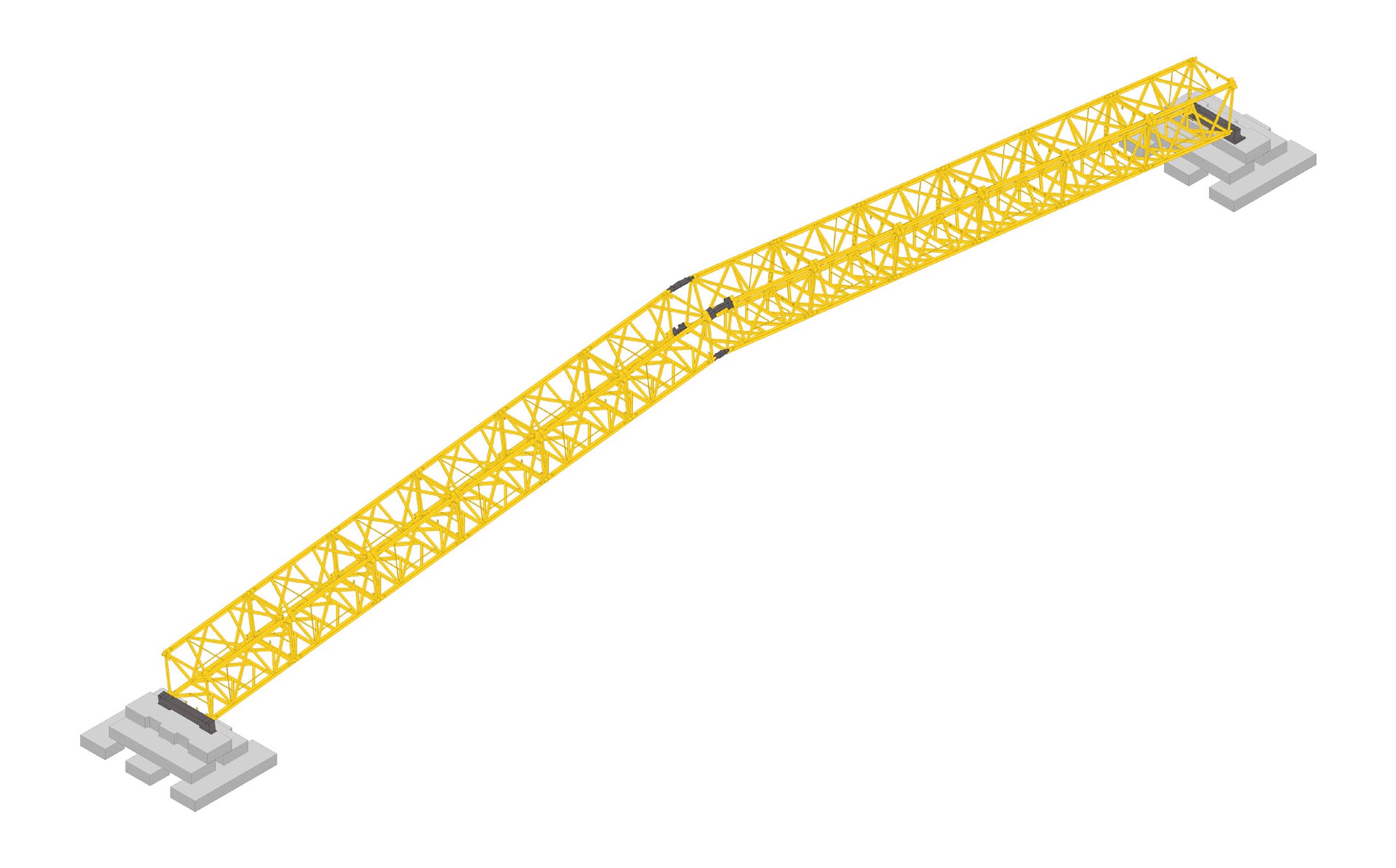

For four days, the transitory footbridge provided pedestrians with an unprecedented connection between the two banks of the Charleroi Canal. Spanning a distance of fifty metres, it consisted of two symmetrical slightly angled sections converging at an obtuse angle with the vertex over the centre of the canal. Apart from making a more resistant structure, this double slope produced sufficient clearance to ensure that the bridge would not obstruct the usual boat traffic along the canal. The middle point also became a lookout with hitherto unseen views along the course of the canal. Moreover, the slope concealed the pedestrians on the other side of the bridge in such a way that it appeared shorter, a visual effect akin to that of the bridges of Venice.

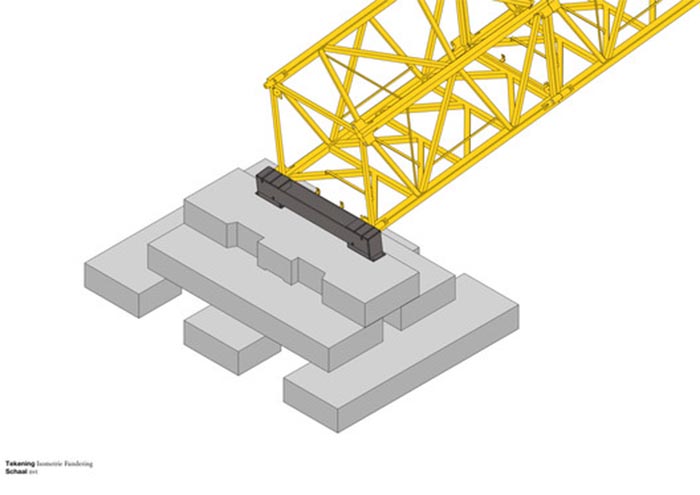

The two identical sections were recycled, reusable elements consisting of rented components of the main tower mast of a typical building-site crane. Framed by lattices of yellow metal bars, the vacant square section of this prismatic tower gave the footbridge resistance, transparency and sufficient width for the movement of people inside the structure. Of the four sides, the two vertical edges served as balustrades, the upper side as an open ceiling and the lower side, covered with a wooden platform, provided the flooring.

Of the whole structure, the only components especially designed for the occasion were the joining pieces. On each side of the canal, a metal structure anchored the two sections to foundations made of piles of prefabricated concrete blocks. In the centre of the bridge, four identical metal pieces fixed the two prismatic sections at an angle. The day the bridge was put in place, a large crane truck on one of the banks lifted the two sections, once joined in the middle, and set the structure in place so that it crossed the canal. At the end of the “Festival Kanal”, the bridge was removed as easily as it had been installed, leaving no trace of its existence on the canal-side wharves.

Assessment

Where the bridge did leave an imprint which lasted much longer than four days, was in the collective consciousness. In fact, the “Festival Kanal” footbridge gave rise to discussion about the need to connect the two banksindefinitely. However, this raised more questions. Would such a connection remedy the marginal status of Sint-Jans-Molenbeek and bring the outsider municipality closer to the centre of Brussels? Or, rather, would gentrification cross the bridge in the other direction? It would not be the first time that the result of a well-intentioned project to improve an urban area was heightening its appeal as real estate, only to end up expelling the residents with lower acquisitive power. Raising these kinds of contradictions is very much in keeping with the theme of gentrification which dominated the “Festival Kanal” debates.

Also in tune with this discussion is the provisional nature of the bridge, which recalls structures deployed by the military in emergencies. The fact is that, in the Old Continent, there is an increasingly alarming phenomenon of historic city centres which are now losing one of their most singular and authentic characteristics, namely the profusion of local residents and small businesses. All around Europe, the tourist industry and the real-estate market are driving the gentrification of urban areas to the point of destroying the social fabric. It is more and more evident that, rather than revamped public space, these neighbourhoods require public policy to produce emergency solutions. Yet this could give rise to a final paradox: in order to deal with the gentrification of a neighbourhood, would it not be better to provide it with a good stock of public housing before dissipating energy and effort on festivals and temporary structures? The answer is no. Culture, as a tool for social transformation, is absolutely essential for consciousness-raising among citizens. And all too often citizens, even when they risk being expelled themselves, oppose the idea of having public housing in their neighbourhoods. Hence the need for symbols denoting emergency.

David Bravo │ Translation by Julie Wark

[Last update: 09/03/2022]