Previous state

In European towns and cities more than half the public space is taken over by private vehicles. As is well known, the result of this privatisation of streets is a threat to the health of both humans and the planet. Moreover, it is a flagrant example of spatial injustice. The automobile, which moves less than a quarter of the population, marginalises children, old people and everyone lacking the physical or economic resources to drive.

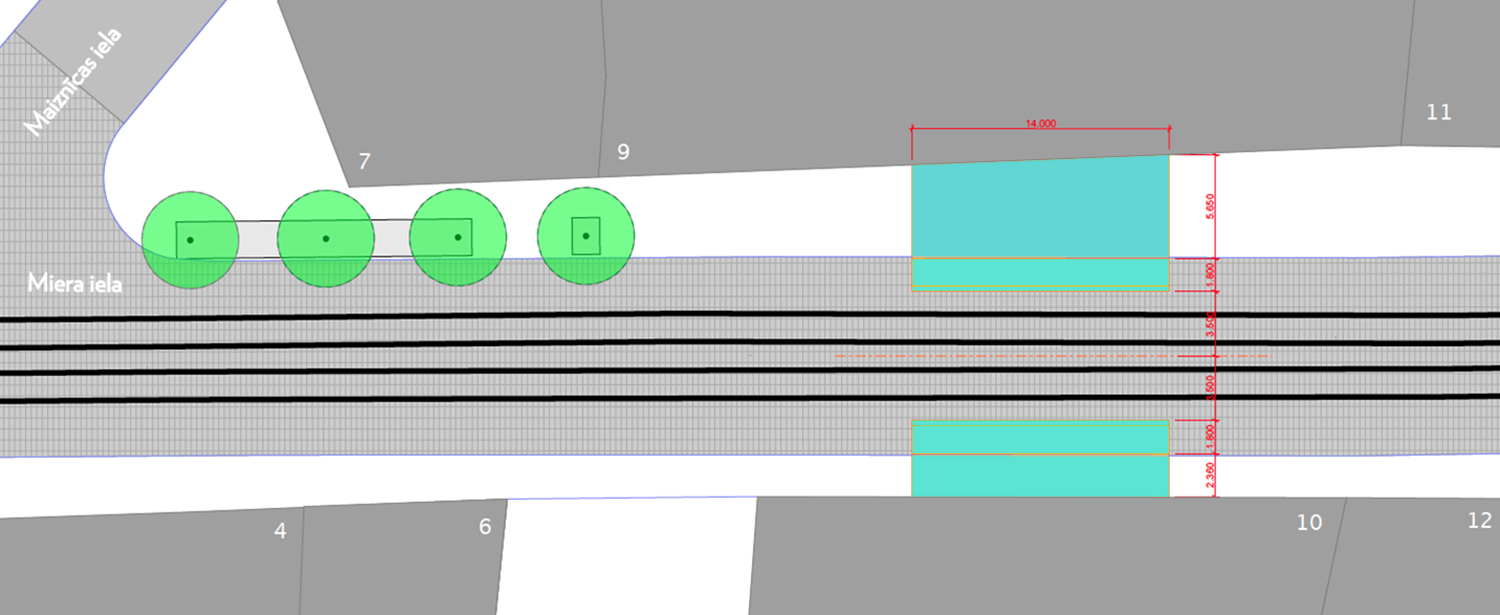

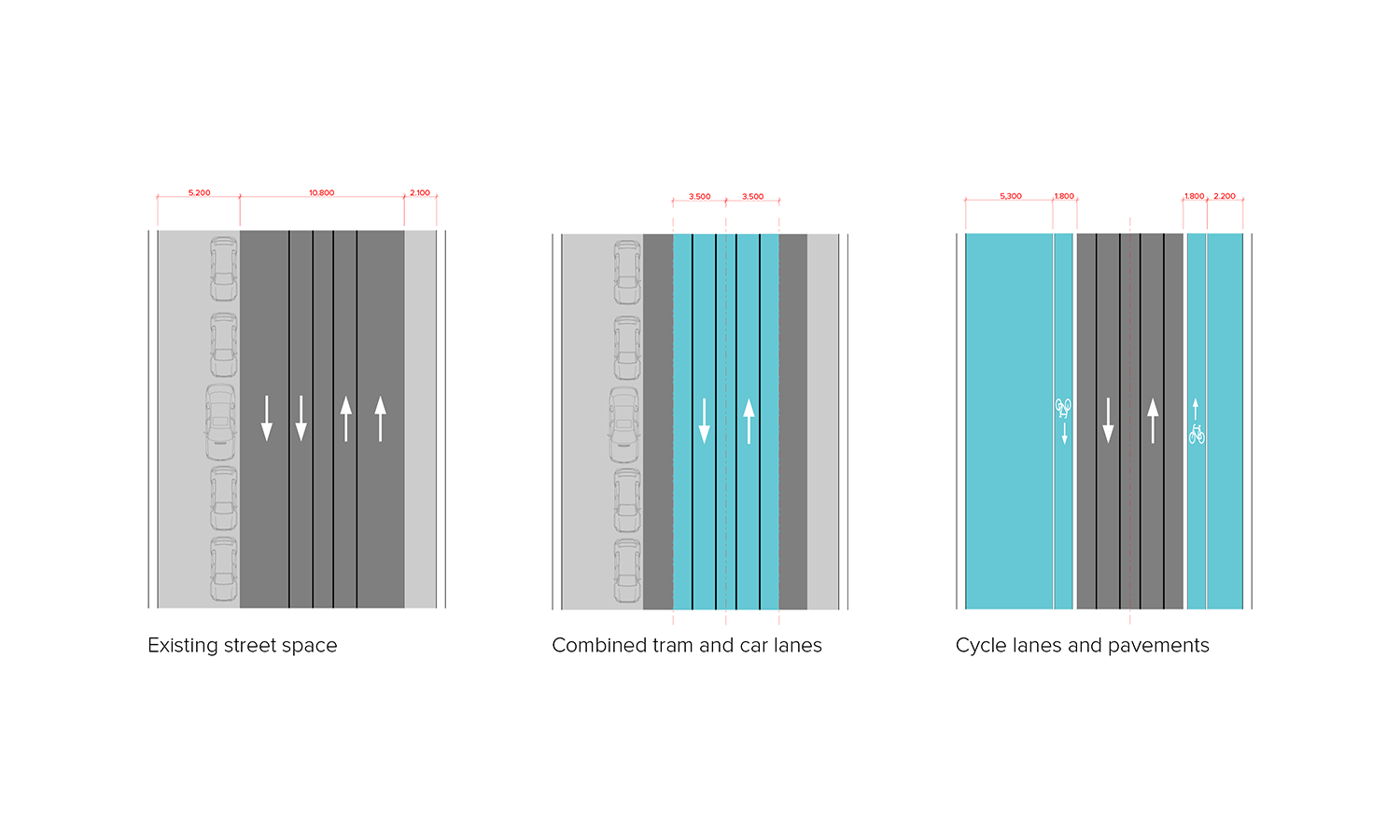

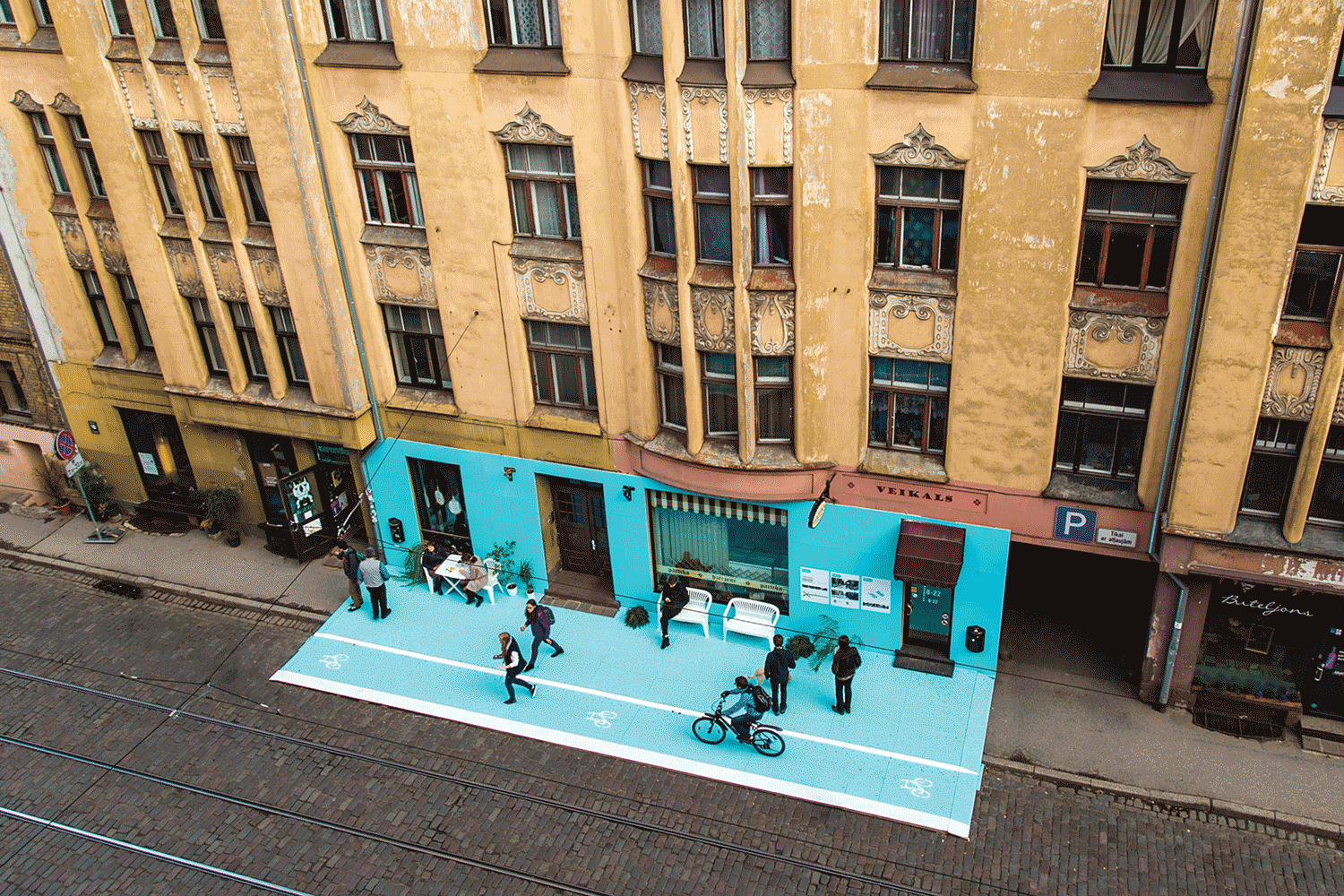

Miera Street is no exception to the general rule. Nine of the about seventeen metres of its width are given to traffic circulating in both directions. Part of the roadway is taken up with two tramlines which are not segregated, which means that they are constantly occupied by cars and, in particular, because the two lateral lanes are normally used for parking. Pedestrians, shopkeepers and cyclists are obliged to share the sidewalk which is some four metres wide at the northern side of the street and less thanthree at the southern side. Hence, anyone using the footpath is constantly dodging people, doors being opened, and signposts.

Aim of the intervention

Fortunately, Miera Street has a long-established and very active local community. Aware of this, a group of young urbanists selected the street in 2014 in order to carry out an experiment. The aim was to make the vexed users of the street aware that the limited existing space could be distributed more equitably. The initiative, part of a bigger strategy of reclaiming more space for bicycles in the city of Riga, also sought to explore the relationship between urban planners who design public space and the community that regularly uses it. The former group may be the ones who know how streets are made but the latter are the experts in using them. In a meeting of both worlds, planners can learn to respond better to people’s real needs, and people can obtain better responses to their needs.

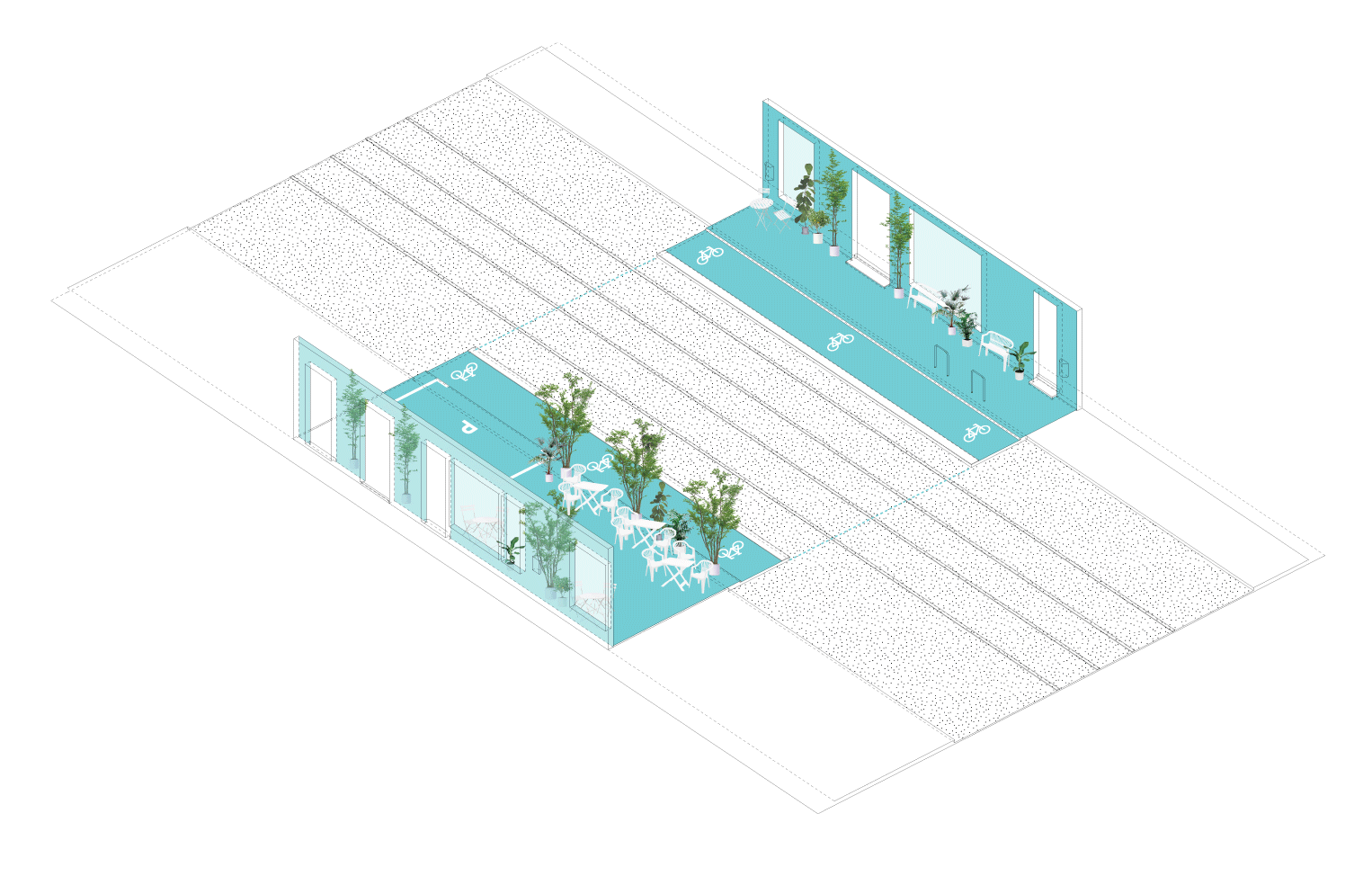

The young urban planners began by drawing up some plans with a view to reducing the space given to cars and then set about illustrating their ideas with perspectives and photomontages since they wanted to involve residents and shopkeepers in their project to improve the situation. The response was positive, although it was not entirely clear whether the people had wholly understood the proposal. And, even when they did understand it, they were not totally sure whether it would work.

Description

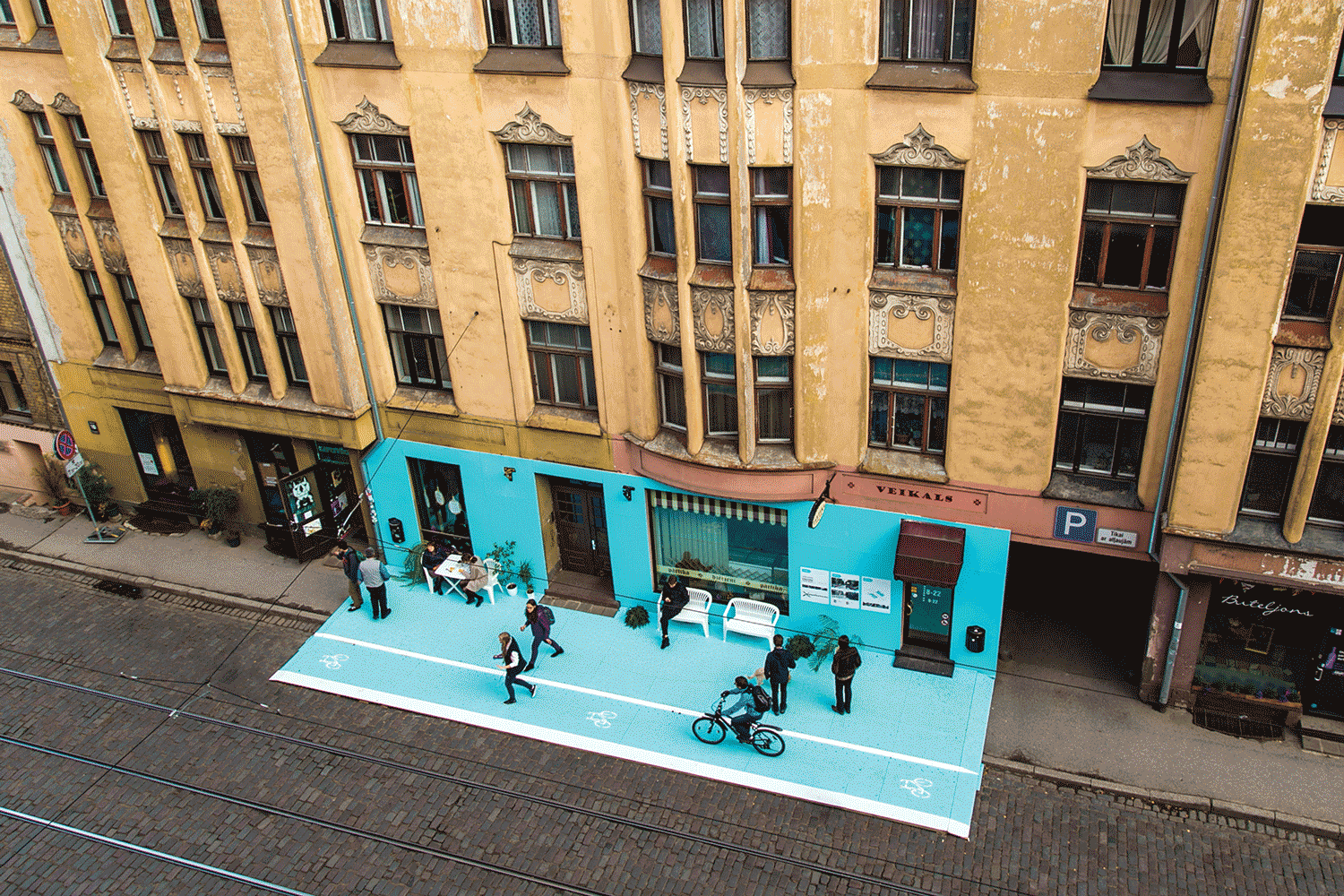

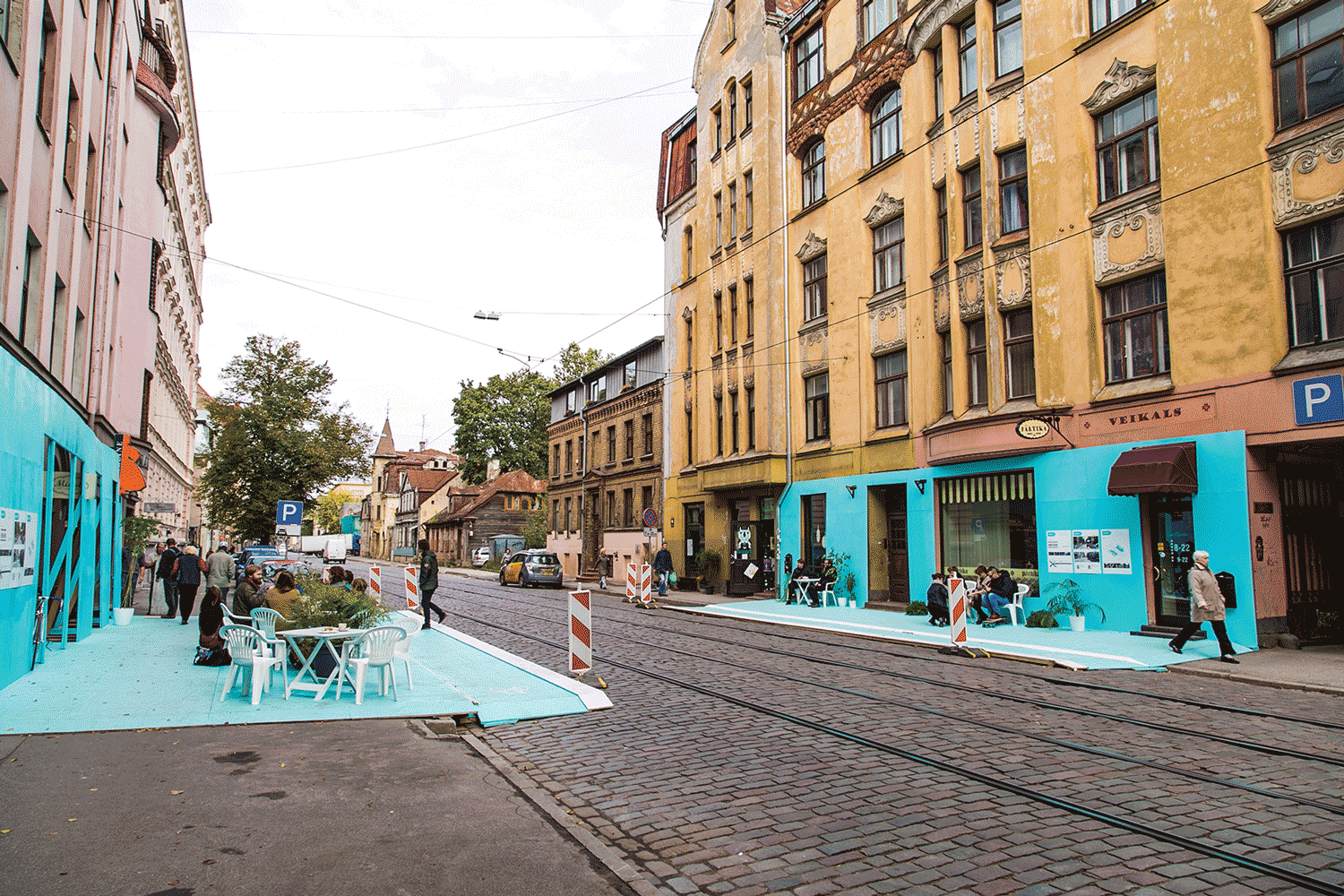

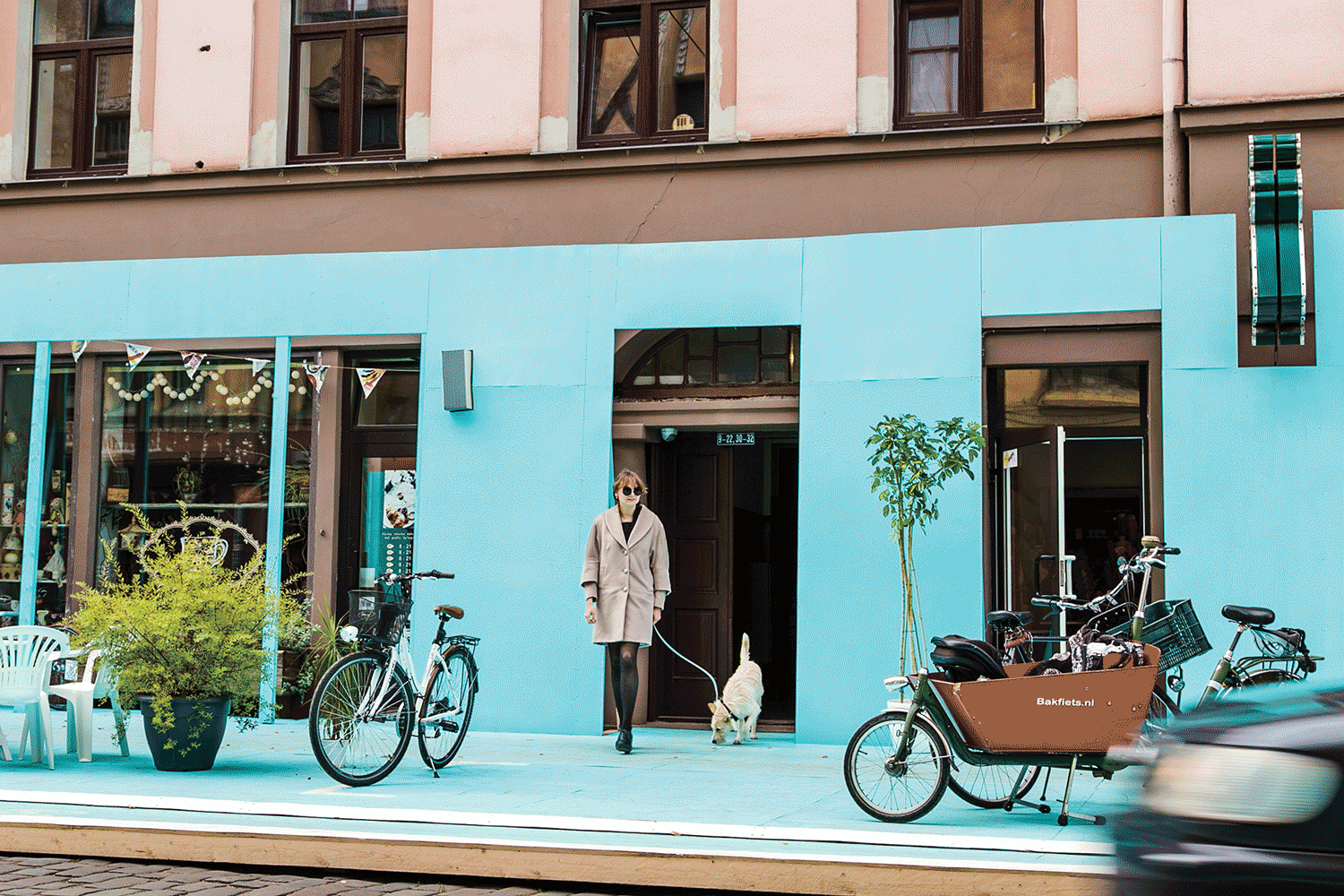

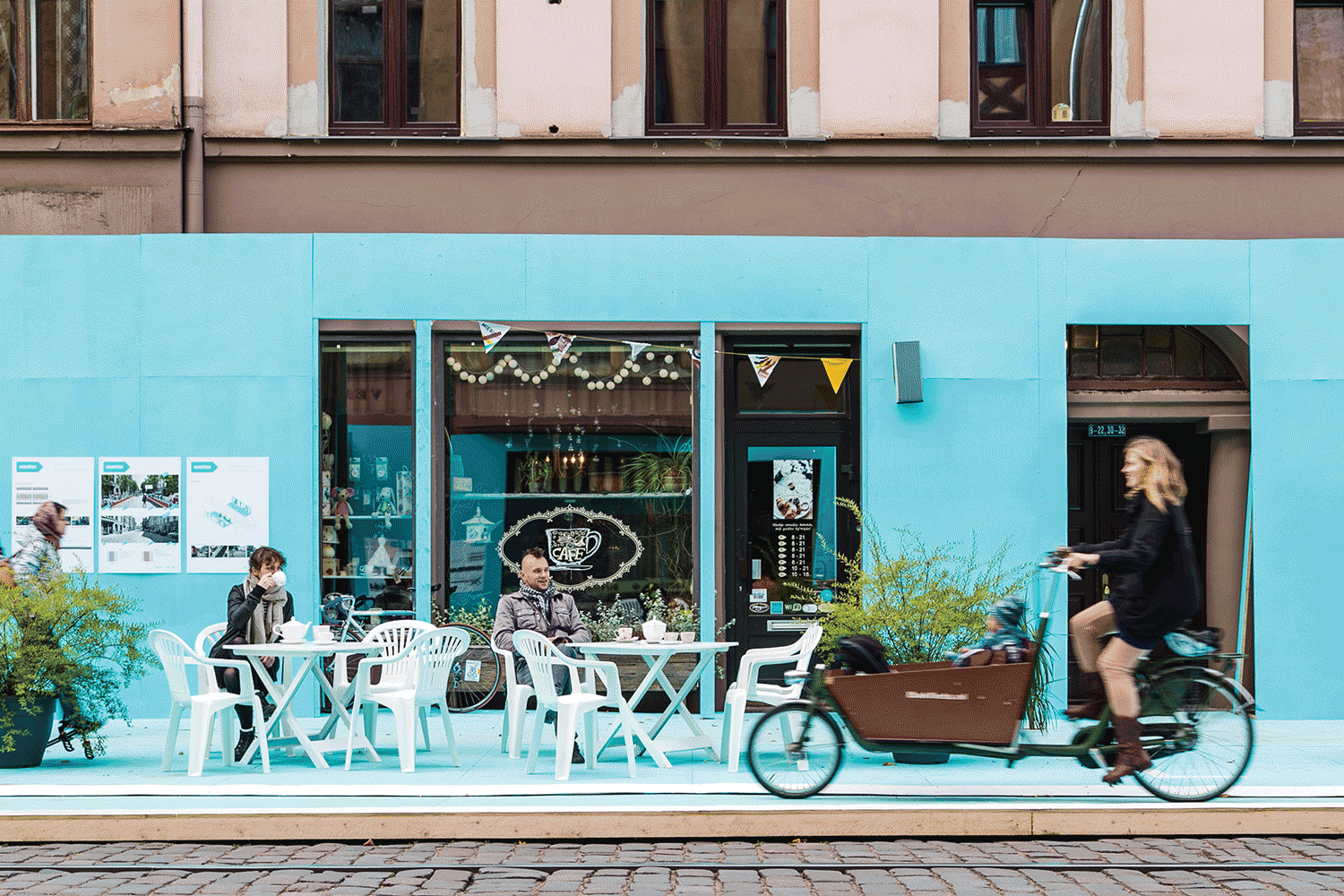

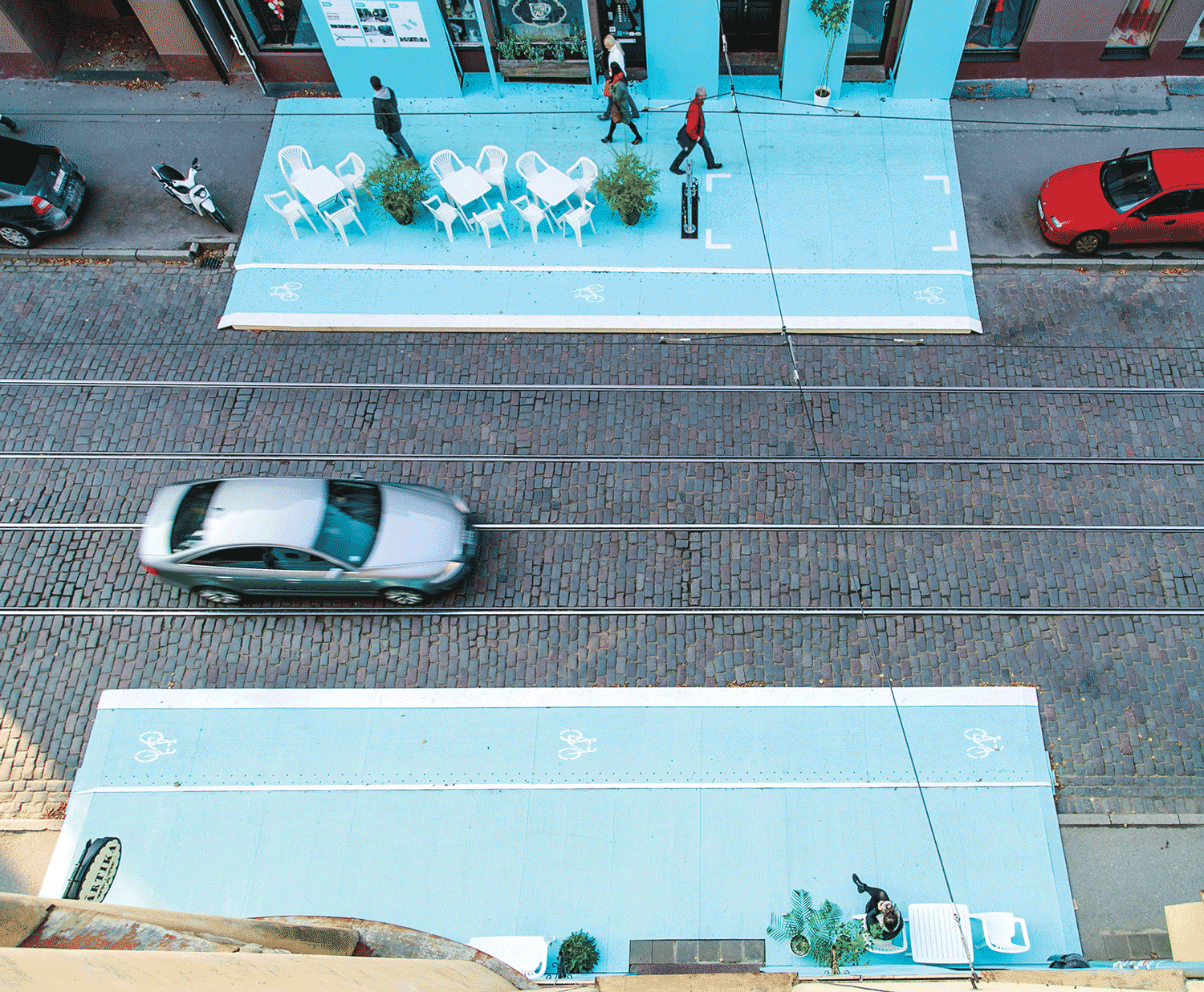

After two years of thinking about the issues, the urbanists decided to test their ideas on the real-life scale. After coming to an agreement with local residents and shopkeepers, they selected a fourteen-metres-long section of Miera Street in addition to raising 7,000 euros to enable them to carry out their experiment, which they named “Mierīgi!”. It took three days to prepare the installation, which only had permission to last on the street for one week. It consisted in a temporary widening of the sidewalks, which were covered with a layerof plywood panels. In order to mark out the limits of the experimental section, they painted the plywood sky blue, giving the scene a certain air of unreality. The extended sidewalks were equipped with benches, flowerpots and a bicycle repair stand, as well as information points telling the public about the aims of the installation.

In fact, the extension of the footpaths was possible thanks to a simple first step. The four car lanes, two in each direction, were reduced to two, which were shared with the tram. This made it possible to insert a bicycle lane next to the sidewalk on each side of the street and also freed space for pedestrians and café owners, who seeing the potential, soon put chairs and tables on the sidewalk for their customers. It was immediately evident to everyone that the quality of life in the fourteen-metre section of Miera Street had significantly improved.

Assessment

The residents and shopkeepers seemed happy to be extras in a brief scene in which they played themselves in a different street. A video of the experiment posted on the social media was reproduced more than 60,000 times with comments from people around the world who wanted to repeat the experiment in their own streets. During the few days of life of the “Mierīgi!” installation, local residents, shopkeepers and pedestrians were constantly discussing the project. Perhaps not everyone agreed about the reconquest of space that has been privatised by cars but it was still clear that tactical urbanism can be an effective way of involving people in matters of urban design. It is a method that tests a space, evaluates the result, and avoids costs arising from design errors. Although it was a fleeting experience, the experiment has left behind a lesson in Miera Street: before conquering city space, it is necessary to conquer the citizens’ awareness.

[Last update: 09/05/2022]