Previous state

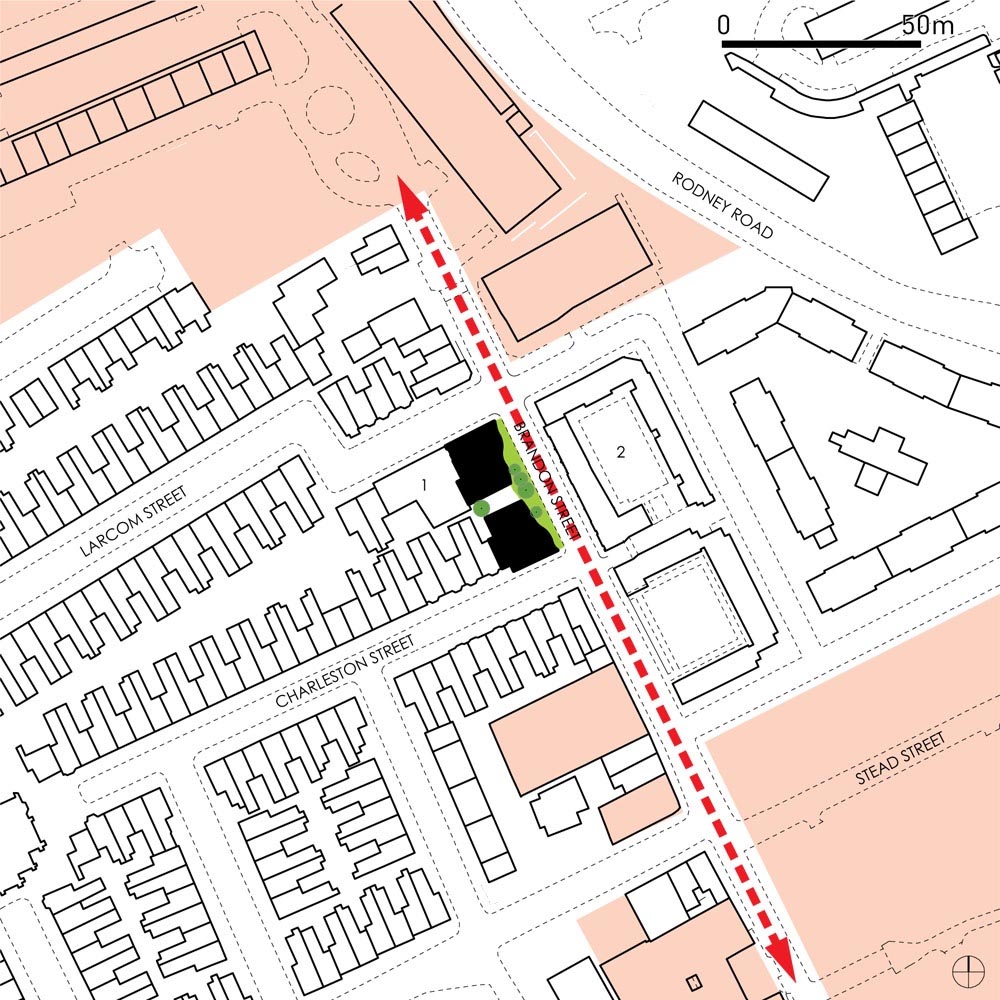

Located in the district of Southwark in South Central London, the Heygate housing estate was one of the city’s biggest. Its concrete blocks were constructed in the 1970s and, until recently, housed more than three thousand people. They have just been demolished as part of a major project of urban renovation in the surrounds of the Elephant and Castle crossroads. This endeavour has not escaped criticism on the grounds that it is encouraging gentrification and forcing part of the population to leave the borough. However, the idea is to re-house former residents in the new buildings which, smaller in size and set in among pre-existing flank walls, are expected to give density to the urban fabric and increase the proportion of social housing in the centre of London.One site available for the new housing was in Brandon Street, which promises to become one of the main north-south axes of the new estate. This vacant block of a little less than two thousand square metres had remained empty since the Second World War bombing attacks on London. Next to an old people’s home, and opposite a primary school, it was surrounded by a low exposed-brick wall which had spontaneously acquired a certain meaning. In effect, both the residents of the old people’s home, their relatives, and children and parents going to the primary school used it as a bench on a daily basis, thus making it a well-known and emblematic part of the neighbourhood.

Aim of the intervention

In 2008 the Southwark London Borough Council called for entries in a competition for the best design of a building of eighteen social housing units in the Brandon Street site. The competition was part of a greater strategy by means of which the Council aims to lay the groundwork for a new way of providing social housing in London. This means moving beyond the standard model of housing estates which, true to an industrial logic based on simplification and repetition, offered a merely quantitative response to the need to put roofs over people’s heads and ended up impoverishing the resulting public space. The new social housing was to have the same quality of construction and aesthetics as private housing, and was expected to fit in with the adjoining pre-existing buildings to become an established part of the existing urban layout. The underlying idea was that residents, besides enjoying the right to housing, should be able to take part in neighbourhood life.Description

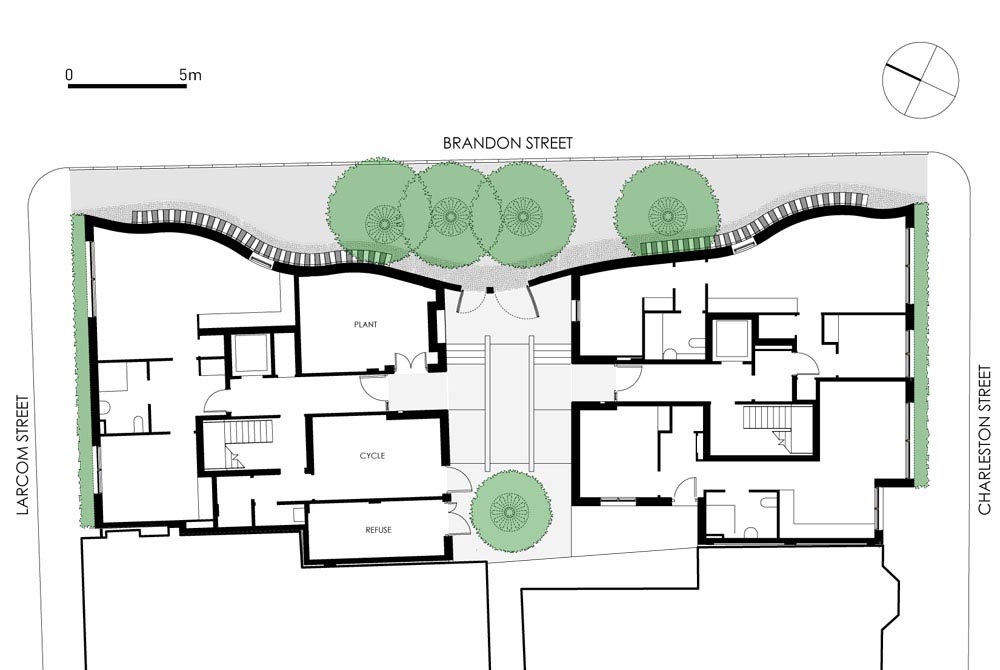

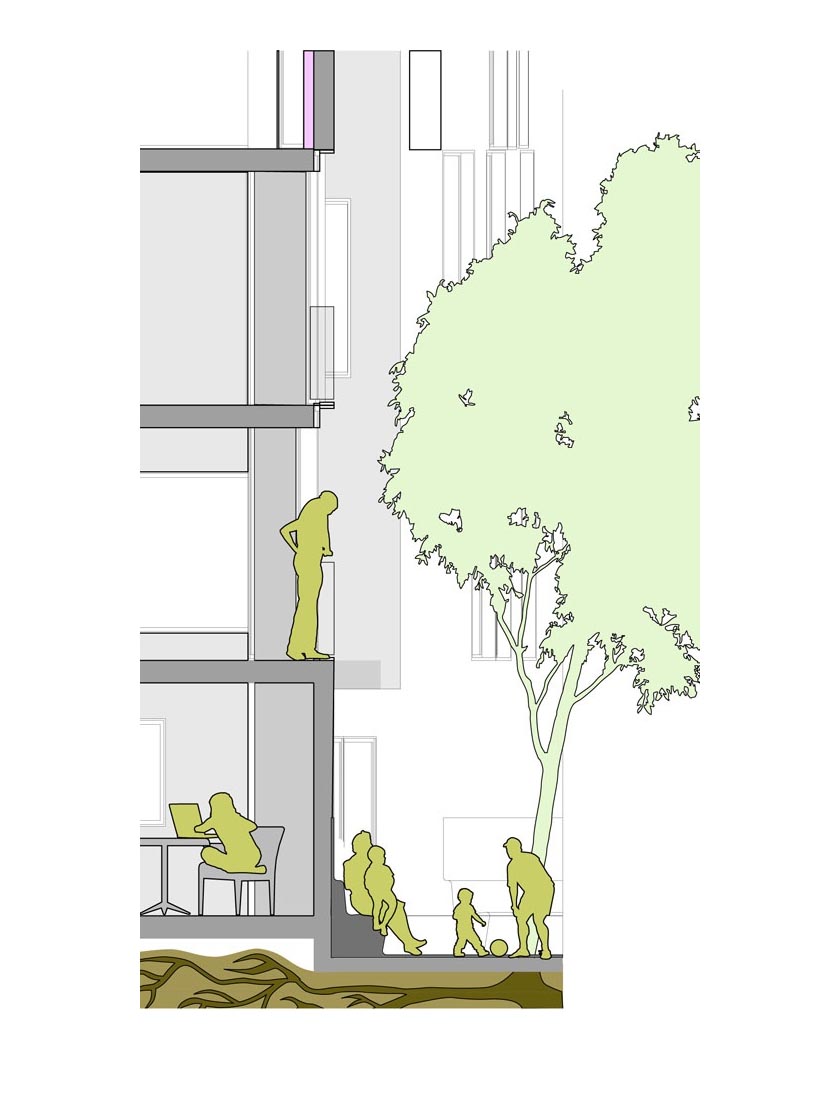

The eighteen social housing units in Brandon Street are distributed between two small buildings separated by a central courtyard. The complex shares a flank wall with the old people’s home and has three facades looking on to the street. The lateral walls are flat and in dark brick, as are the adjacent buildings. However, the Brandon Street facade, at the front of the block, is colourful and undulating. It consists of two separate faces covered in hexagonal ceramic tiles in thirty-seven different tones and distributed in chromatic graduation from honey yellow to burgundy red. These faces, curving like folds in curtain material, create concavities which allow space for the leafy tops of four pre-existing trees. They also retreat from the line of the street, indicating the courtyard that gives access to the flats and widening the pavement in front of the primary school. This was the location of the old wall where people used to sit. They can now sit in the same place on two continuous prefabricated concrete benches offered by the new building. These are some ten metres long and follow the undulating bases of the two faces of the building but without conforming to the chromatic scheme since they stand out from the colours of the buildings with their vertical grey and white stripes.Assessment

Moving a building back in order to give more square metres to a footpath is a generous and quite an unusual gesture in a housing project today. It is also remarkable that a contemporary building should recognise an old neighbourhood custom and offer a continuous bench on the street. Unfortunately cities tend to show a proliferation of disciplinary architecture which rejects unwanted people, not only from thresholds between interiors and public space but also in the design of street furniture. Social housing enhanced by curves and colours to give a friendly, jovial impression in the street is not common either. Normally, these kinds of projects are expected to have a look of formal severity because they are public, and this ends up diminishing the urban landscape.All these exceptions demonstrate that, much more than a welfare measure that puts a roof over the heads of those in need, social housing can extend its benefits to society as a whole. Indeed, affordable rented housing is an instrument that can democratise the city, giving it denser and more mixed neighbourhoods, making mobility more sensible, and streets safer and easier to maintain. Just as the urban setting is determinant in the value of a house, homes are also essential in determining the quality of neighbourhoods. Hence public space and domestic space cannot be treated as two separate assignments. Each one must cross the thresholds that divide them, and there is no doubt that the benches in Brandon Street are doing just that.

David Bravo Bordas, architect.

[Last update: 02/05/2018]