Previous state

Savamala is one of the most beautiful neighbourhoods in the centre of Belgrade. Looking over the eastern bank of the Sava River, it is full of historic corners and buildings of great heritage value. However, the scars of several wars, the traumatic transition after Soviet rule and the dismantling of public services imposed by neoliberal policies have wrought havoc in the neighbourhood and doomed it to economic decline and social exclusion.The general situation is palpable in its public spaces, now stigmatised as untrammelled zones of prostitution and criminal activities, invaded by heavy, intense traffic and blighted with endless traffic jams and high levels of pollution. The built-up area is pocked with vacant lots and strewn with closed businesses and derelict buildings. One example of this was the nineteenth-century “Spanish House” (Španska kuća, in Serbian), which occupies an empty stretch of the riverbank, next to the railway line and in the shadow of Brankov Bridge. It had lost its roof and slabs years earlier, making it necessary to shore up the facades. From the street, the empty window frames gave glimpses of the sky.

Aim of the intervention

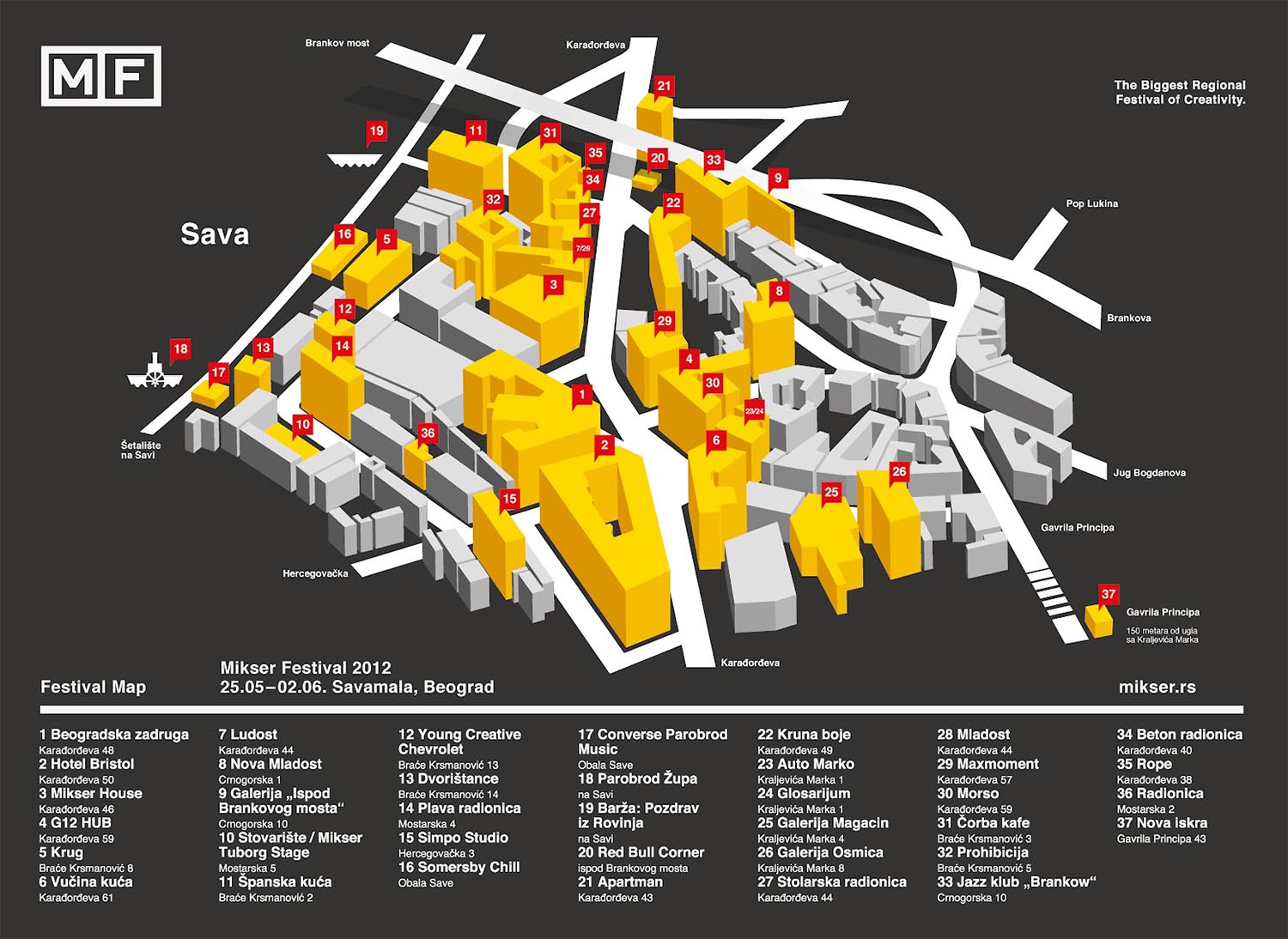

Early in 2012, “Spanish House” was earmarked as the temporary home of the “Urban Incubator” culture programme. The initiative, part of the “Misker Festival” programme and supported by the Goethe Institute of Belgrade, the City Council and the Savski Venac district, brought together an international group of students, experts, artists and activists who took over the building for a period of twenty months.The project of temporarily rehabilitating “Spanish House” and improving several points in its immediate surrounds was achieved with a budget of €50,000 and the labour of the group. The aim was to acquire in-depth knowledge of Savamala and to involve the local residents in developing a strategy for improving their neighbourhood. The participants trusted in social transformation, cultural creation and economic innovation to contribute towards a better quality of life in the zone, combat its marginal status, equip it with areas on a human scale and encourage the people to take charge of their own environs.

Description

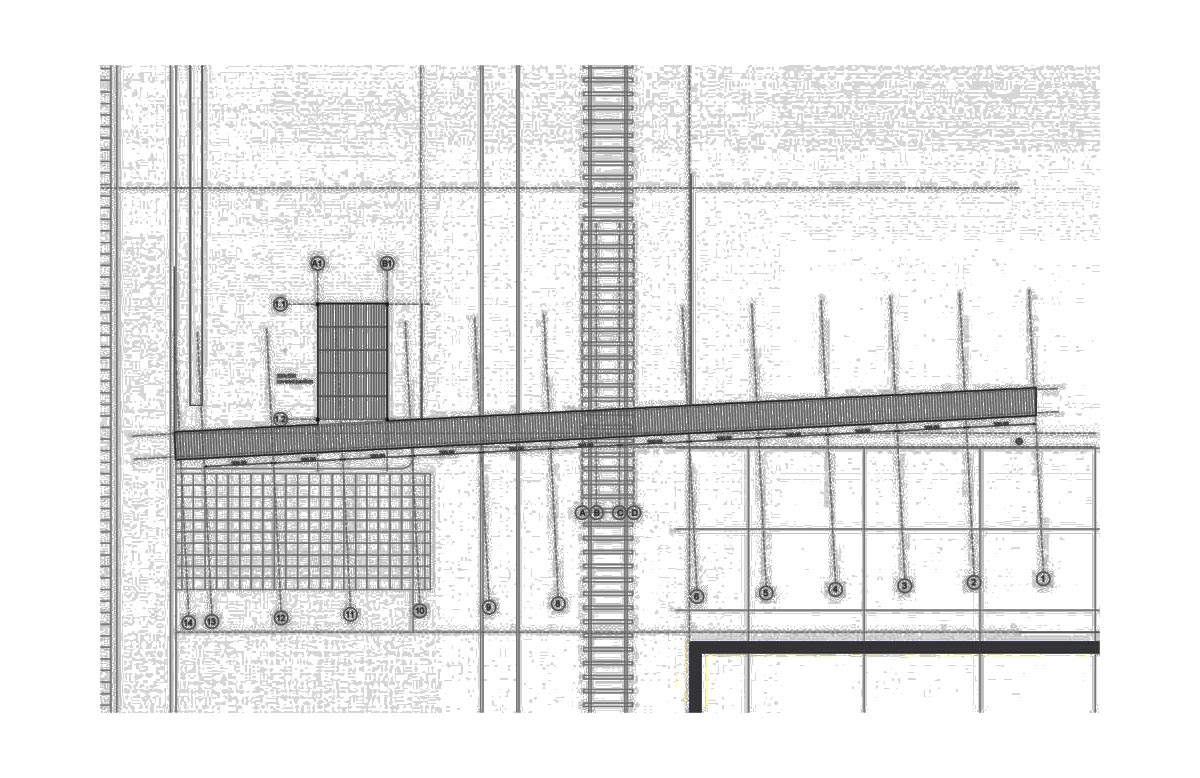

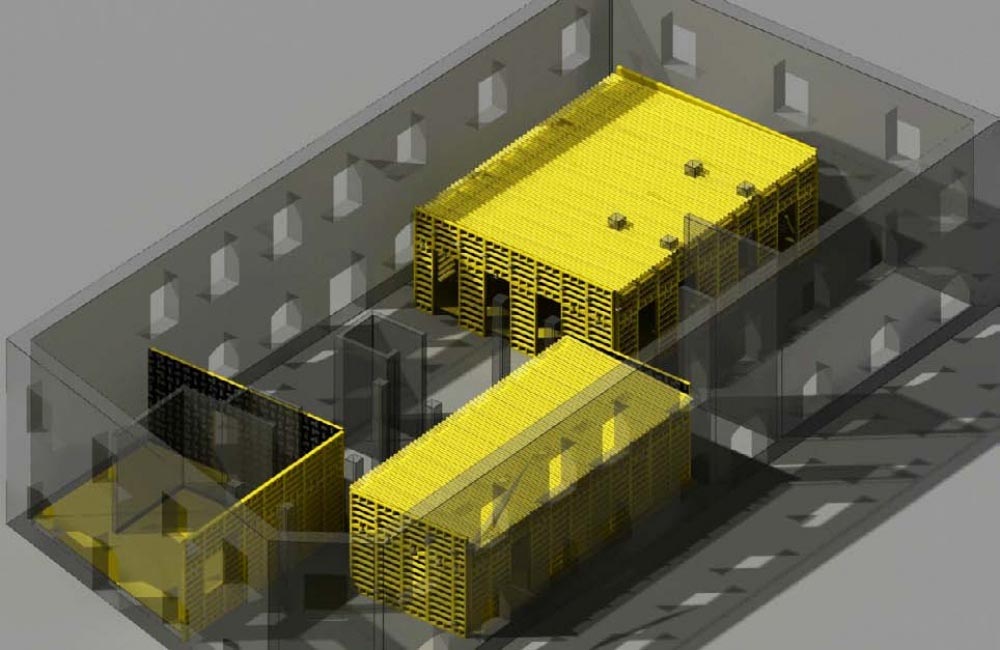

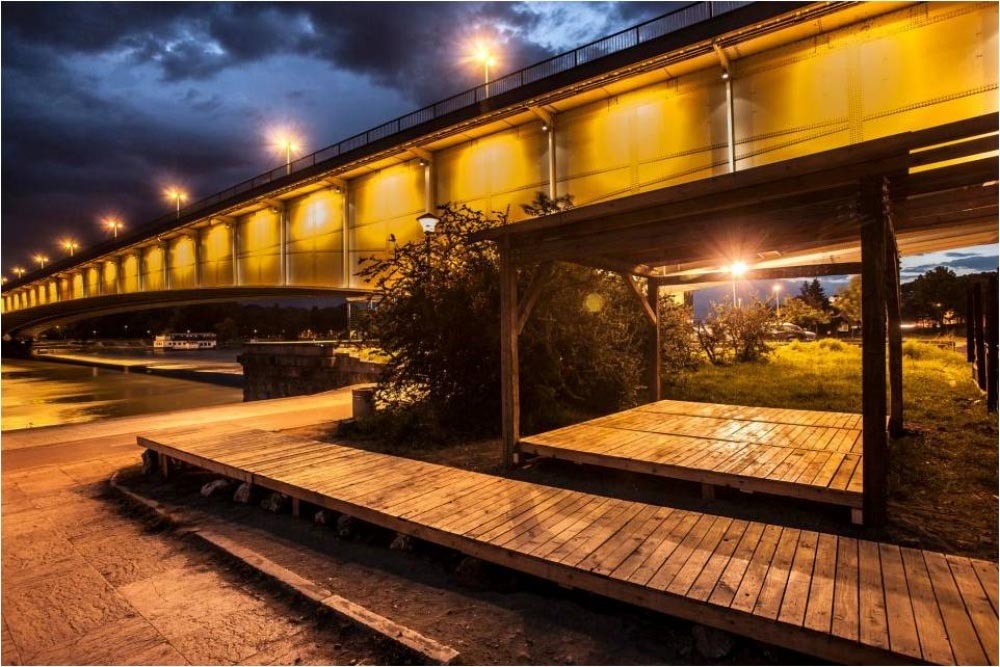

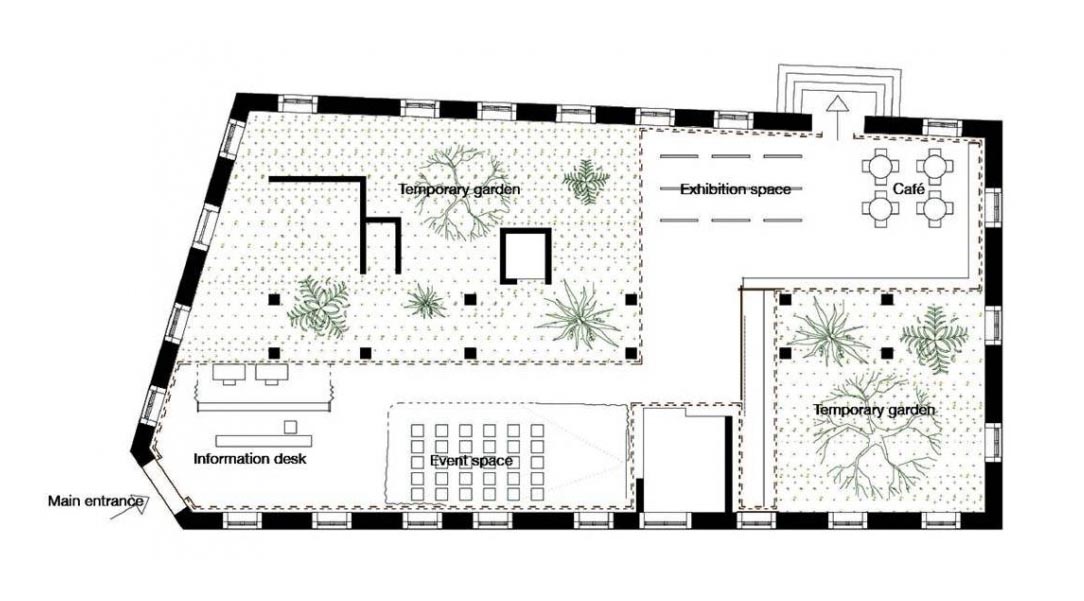

A rectilinear walkway covered with wooden planks was installed between Brankov Bridge and “Spanish House”, starting from the street in front of the building, crossing the railway line at ground level and ending with a platform situated on the river bank. Barriers providing protection from the railway line were erected alongside the walkway, and a porch was constructed to shelter outdoors activities.In the area of almost four hundred square metres delimited by the facades of “Spanish House”, two temporary pavilions were installed, unaligned in order to make room for two garden spaces. The roofs and walls of the pavilions were built with recycled formwork panels. The one nearest the entrance housed an office for attending to residents and offered a space for holding assemblies, workshops and meetings. The other pavilion accommodated a small cafeteria and an exhibition space used for informing residents about the progress being made by the initiative.

From the very beginning and throughout the process, “Spanish House” became an increasingly popular meeting place for experts, students, artists, activists and growing numbers of local residents who became more and more involved with the project. Renovated spaces in both the open air and inside the building became venues for a considerable number of events with large audiences attending lectures, debates, assemblies and seminars with a view to devising strategies for improving the neighbourhood.

Assessment

Although it was transitory, the appearance of such a vibrant civic centre as “Spanish House” in the rundown neighbourhood of Savamala brought incalculable benefits. Working together, the residents, previously sunk in frustration and apathy, discovered the value and potential of their surroundings and the power of their own labour. The self-managed space, with fluid relations between roles and disciplines and a cooperative spirit, stimulated people to present a great number of proposals. This time “urban renovation” was not undertaken from the offices of experts or powerful people but at the grassroots level, the lowest layer of the social pyramid. It is to be hoped that the seeds sown in this “Urban Incubator” will continue to bear fruit for a long time.David Bravo

Translation by Julie Wark

[Last update: 18/06/2018]