Previous state

Increased use of gunpowder by the artillery in the sixteenth century relegated Europe’s medieval fortified walls to obsolescence. In the case of Palma, the capital of Mallorca, this new situation coincided with a period of great instability in the Mediterranean. Palma was obliged to bolster its fortifications with thirteen V-pointed bulwarks, making them less vulnerable to projectiles and offering better visibility of attackers. By the nineteenth century, however, improved ballistics meant that city walls could no longer perform their defensive function and the city of Palma demolished them in order to expand freely. The only sections that were saved – because they represented no obstacle to urban growth – were the sea wall and the two bulwarks flanking it, Baluard de Sant Pere (St Peter’s Bastion) in the west and Baluard del Príncep in the east. The maritime façade of Palma still rests on this fortified section of one kilometre in length, presided over by the city’s gothic cathedral, the Royal Palace of La Almudaina and the buildings of the Episcopal complex. Until well into the twentieth century, these monumental constructions offered sailors a highly representative image of the city, especially when reflected in the waters lapping at the foot of the wall.

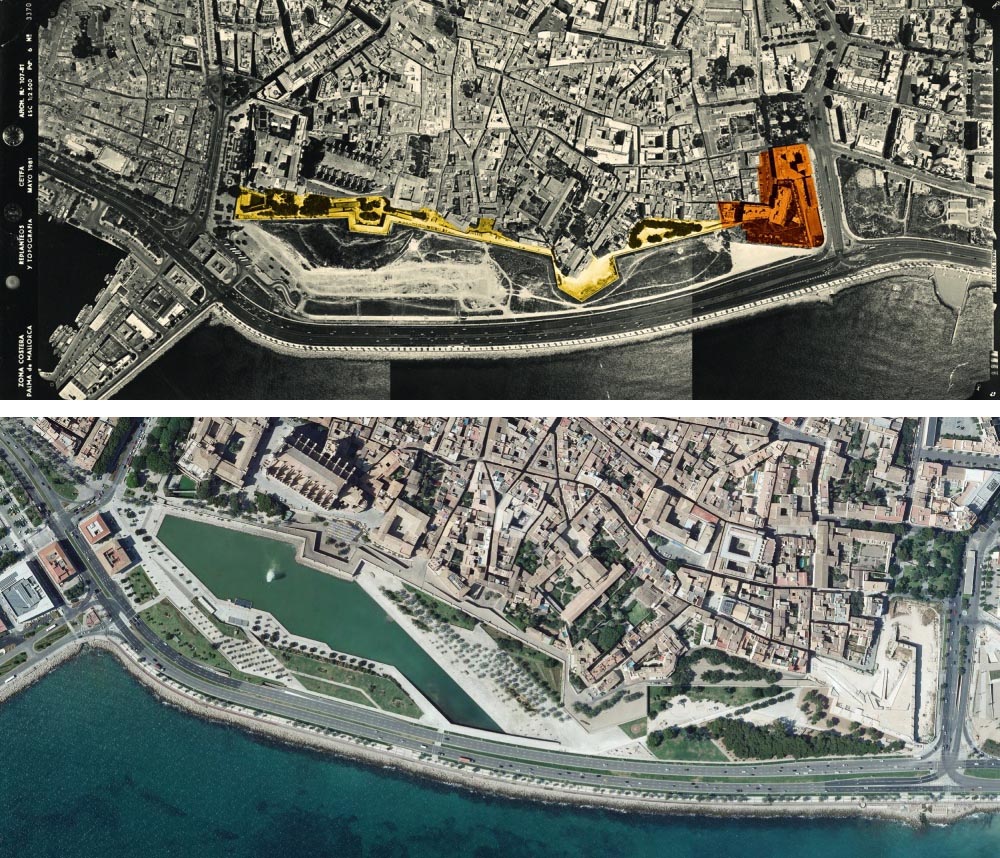

Nonetheless, it took the authorities some time to recognise the heritage value of this fortified seafront, which no longer had any military use. Indeed, it was pressure from the citizens that snatched it from the claws of private interests. During the 1960s, at the height of the dictatorship, the army sold off the Baluard de Sant Pere to the private sector after which it was partially demolished for a real estate project. Fortunately, in the waning years of the regime, the citizens mobilised to halt the operation and managed to get the bulwark expropriated and heritage listed. Thanks to their determination, it now houses the Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art. Similarly, at the foot of the wall, land reclaimed from the sea for the railway line and the airport road was saved from further use as a large car park thanks to residents’ protests at the end of the 1970s, which resulted in the opening of the Parc de la Mar (Sea Park). Now this public space of nine hectares has a large saltwater lake which once again reflects Palma’s maritime façade. The Baluard del Príncep was less fortunate as it was irreparably damaged by the Franco regime between the 1950s and 1970s when it was used to construct three residential buildings to house military men and their families. By the end of the dictatorship the rest of the sea wall was in a state of neglect and its future was uncertain. Rather than being an accessible feature of the city whose historical relevance could be used for educational purposes, it constituted a barrier between the old centre and the Mediterranean.

Aim of the intervention

In 1973, the Ministry for the Army transferred ownership of the sea wall to the Palma City Council, which then listed it as a historical heritage site. Nevertheless, the city made no serious effort to recover it until democracy was established. After 1983, the Council drew up a plan to restore the maritime façade and open up the fortifications as a public footpath for the citizens who had so vigorously defended them. The operation, which was carried out in successive stages over more than three decades, constructed ramps and steps to connect the top level of the cathedral with the lower level of the Parc de la Mar. The wall was crowned with a walkway of more than a kilometre in length, from Baluard de Sant Pere to Baluard del Príncep.

In 2000 the three housing blocks which the army had constructed on the latter bastion were expropriated and the 200 people still living there were indemnified. Seven years later, the demolition of the buildings restored the continuity of the old maritime façade and the Baluard del Príncep gained more than eight thousand square metres. The space was for the city’s use and, in 2009, the City Council and the Ministry of Public Works allocated three million euros for its restoration. This intervention, the final stage in the rehabilitation of the sea wall, made it possible to complete the maritime walkway, offering a lookout with exceptional views over the Mediterranean.

Description

While the sections of the wall delimiting the bastion were in quite a good state of conservation, the esplanade crowning it had lost its original configuration with the construction of the three now-demolished residential buildings. Instead of a false restoration, it was decided to distribute the space into three large platforms at different levels, adapted not only to the shape of the wall but also to the footprint of the demolished buildings. The lowest platform is at the same level as the streets of the old city centre; the middle level meets the footpath running along the length of the top of the wall; and the upper level looks out over the bay of Palma.

Both the platforms and the ramps and steps joining them are lined by thick walls of sloping surfaces which give them an appearance of the massive solidity of the old wall. And, like the old wall, the cathedral and the Palace of La Almudaina, the new walls are made of blocks of sandstone which will age rapidly so that the new section will soon blend into the rest of the seafront. This material, which is very abundant in the Balearic Islands, is easy to work with, although it crumbles easily. Hence the corners of the walls have been finished with another type of harder sandstone of a similar colour.

The ground of the platforms and ramps has been paved like the rest of the seafront walkway with austere, hard-wearing, prefabricated L-shaped concrete pieces which are joined in two different ways. On flat surfaces, open spaces are left for grass to grow up through them while the pieces on sloping ground are tightly fitted leaving no spaces in order to ensure that rainwater will not wash away the earth. Like the rest of the maritime walkway, this section has bronze lamps fitted into the lower part of the wall, shedding light on the perimeters of the areas where people walk. At points where paths, steps and ramps flow together and more activity is envisaged, this basic lighting is supplemented by Y-shaped street lamps.

Assessment

Just as the Baluard de Sant Pere houses the Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, it is anticipated that the Baluard del Príncep will have a city wall interpretation centre at some time in the future. Meanwhile, the restored bastion is, in itself, a fine example of continuity at a time when which rupturism and originality are brandished as overriding values in many works of urban transformation. The intervention in Palma is the culmination of a long and complex process by means of which the city has recovered the entirety of its sea wall as public space. While many mayors seem to be obsessed with initiating and completing the results of their own work, in this case there has been enduring agreement lasting over eight legislatures of ideologically different hues.

The life of a seriously threatened heritage element has therefore been saved so that, when no longer used for military purposes, it has taken on a superlative civilian function. The idea of continuity is as well expressed in the longitudinal sense of the new maritime walkway, and also with coherent use of the same paving and lighting elements in the successive phases of the project’s completion. Yet perhaps the most valuable continuity underlying this intervention is the connection that has been established in the transversal sense of the wall, which was formerly an impregnable barrier and now an intermediary in the relationship between the old city centre of Palma and the Mediterranean Sea.

David Bravo Bordas, architect.

[Last update: 15/11/2021]