Previous state

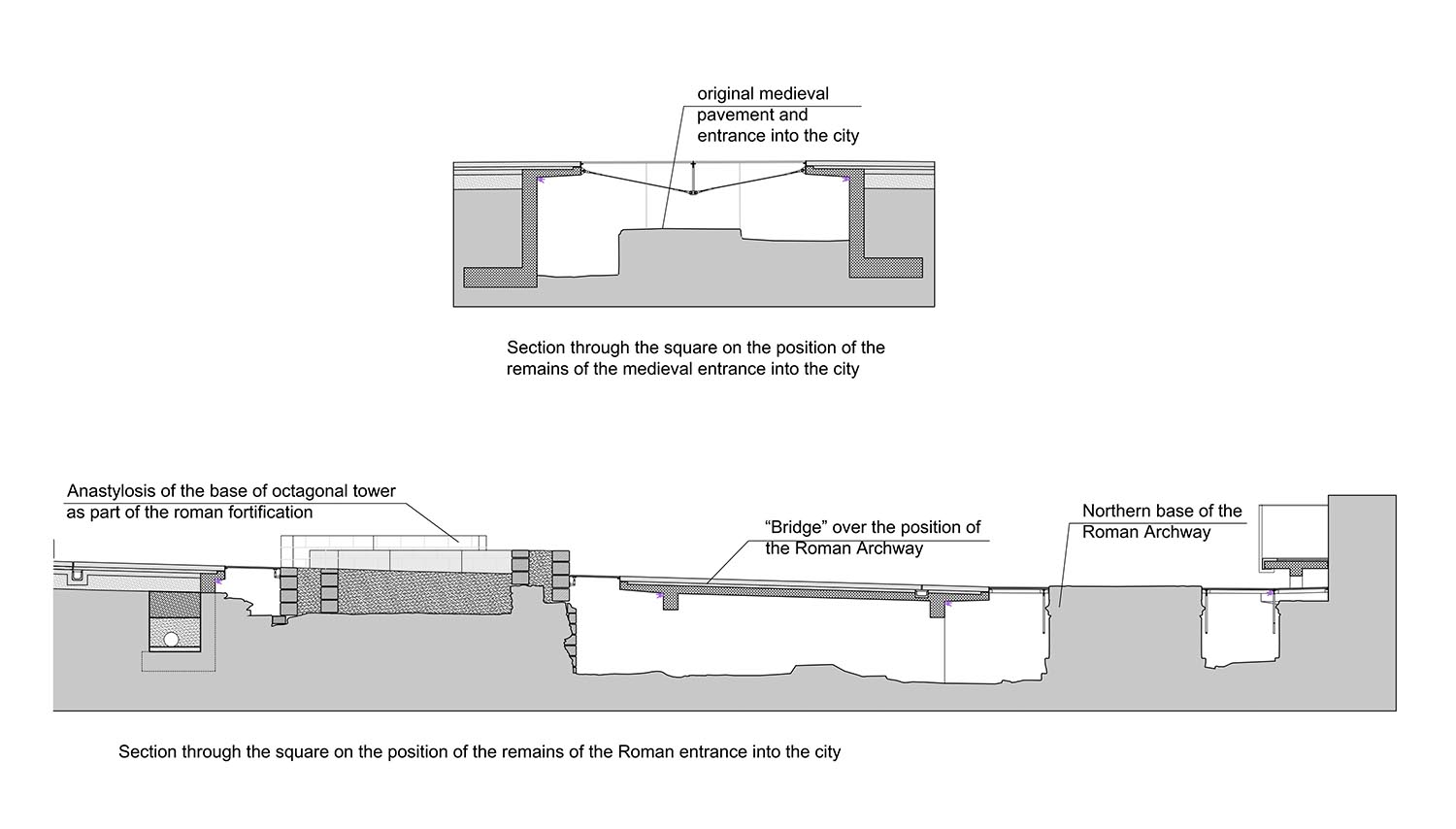

The decumanus, one of the two main axes of the Roman city, now in the form of a main road, is still the organising principle of the old centre of Zadar. It starts in the square where the forum once stood and goes straight to the south-eastern edge of the peninsula on which the old centre of the city is built. The gateway in the city wall which stood from Roman times until well into the Middle Ages is to be found in this site of today’s Petar Zoranić Square. The square, with its bustling, typically Mediterranean atmosphere, has buildings of great heritage value, including the church of Saint Simeon, the Captain’s Tower, and the Grimani Bastion. There are also two beautiful, impressively tall centenarian sycamore trees. The space is also connected with the Five Wells Square, which is surrounded by a small park, a frequent venue for concerts and other open-air activities.Nonetheless, Petar Zoranić Square was in a dilapidated state after the 1990s when it was damaged by some of the bombing attacks in the Yugoslav Wars. Early this century, when work was being done to improve underground infrastructure, some highly significant ruins were found. The most remarkable, in the very centre of the square and only a metre and a half beneath today’s paving, is the octagonal base of one of the towers that once flanked the gateway in the Roman wall. Five metres north of this is the foot of a Roman arch, while five metres to the east are the remains of the gateway in the medieval wall.

Aim of the intervention

The importance of the find meant that the run-down state of the square became inexcusable and its renovation could be delayed no longer. In 2009, the Zadar City Council made a call for entries in a competition seeking proposals for making easy viewing of the medieval and Roman ruins compatible with the everyday uses of the square. It was hoped to show and give dignity to the ruins without condemning such a lively, bustling square to the status of an open-air museum. It was also necessary to achieve a versatile layout of the paving and street furniture in such a way that they could be used for everyday needs without creating obstacles for the future holding of crowd-pulling events.Description

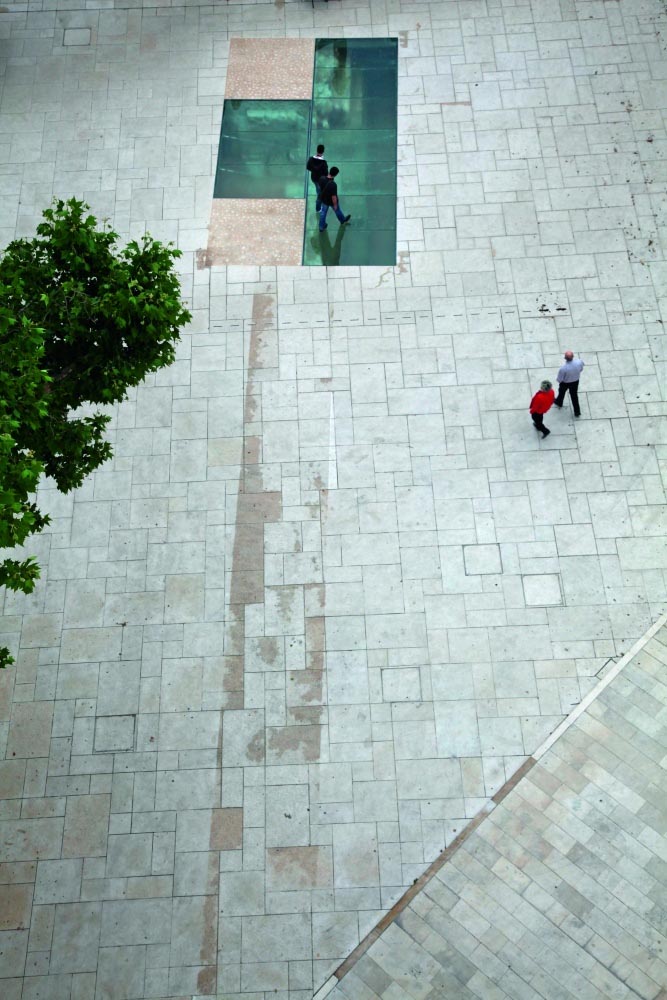

For some time, the archaeological exploration and excavation work left the subsoil of most of the square uncovered. Once the work was completed, the site was covered again and the square paved with a single flat surface of limestone plaques of different sizes. The paving is only interrupted at three points where the plaques are replaced by glass sheets embedded level with the surface. Without any kind of architectural barrier to movement in the square, the glass allows people to view the ruins underground. It is supported by slender beams and steel braces and covered by a transparent anti-slip film which protects it from erosion and scratches. From one side to the other of the medieval gateway, a different treatment of the paving stones indicates the line of the wall. The base of the octagonal Roman tower has been restored by means of the technique of anastylosis whereby a section has been reconstructed. Now it rises up to a height of approximately forty centimetres above the glass that surrounds it to form a bench. On the south-eastern side of the square, the trunks of the two pre-existing sycamore trees have been surrounded by parterres planted with grass and delimited by two lineal wooden benches.Assessment

Longevity is one of the outstanding values of European cities. The historic centres of cities in the Old Continent are unique in their abundance of remains from as long ago as the Roman or medieval epochs. Nevertheless, this generous legacy obliges the present to continue a relationship with the past, which is not always easy. The bequest of the past has frequently created obstacles for present-day needs, and the present-day does not always have enough feeling for, or understanding of the past. There are more than a few European public spaces where the weight of history, sublimated into excessive museum-style pigeonholing, or turned into a tourist spectacle, chokes everyday life. Neither is there any lack of cases where the impatience of our times rides roughshod over valuable relics, destroying them irremediably. Petar Zoranić Square is a happy episode in this long, complex relationship. Without creating any obstacle to present-day existence, the sheets of glass laid level with the ground offer three windows with views onto the past. However, the project has gone beyond being satisfied by the coldness of a visual relationship mediated by glass. The past has risen in the rebuilt octagonal tower, which has been brought up, outside the limits to which it was confined in the archaeological underworld, to make it a functional bench, in constant physical contact with real-life activities today.David Bravo Bordas, architect.

[Last update: 02/05/2018]