Previous state

In the 1870s, several squares in Madrid were covered with graceful metal structures which transformed them into municipal markets. One of these was the plaza de la Cebada (Barley Square), one of the oldest in Madrid and given this name because in the sixteenth century extramural tillage farmers piled their harvested crops there before winnowing. Ever since then the square has been a centre of social interaction in the working class neighbourhood of La Latina. In the middle of the twentieth century, however, the nineteenth-century markets fell prey to an obtuse obsession with hygiene that pronounced them obsolete, whereupon they were replaced with new, much heavier concrete buildings that were closed in on themselves. The case of La Cebada market was compounded in 1968 when a municipal sports centre was appended to it, thus taking up the last free space in the square.With the arrival of the twenty-first century, the Madrid City Council presented a plan for reclassifying the two public facilities, which were to be rebuilt and their management taken over by private concerns. The sports centre was demolished in 2009. It was the only sports facility in the neighbourhood but, owing to the onset of the crisis, nobody was prepared to invest in constructing its replacement. A vacant, sunken area of 5,500 square metres, surrounded by a opaque fence in the very heart of the historic centre of the city, was left in limbo, waiting for better times. After a year of silence, the empty space was the object of an installation conceived as part of the “La Noche en Blanco” (All-Nighter) initiative, which periodically engages in temporary occupations of public space so as to reinvent the relationship between Madrid and its citizens. The space became the venue of a “rain forest” and an open pool which, for ten days that summer, were the pride and joy of the La Latina neighbourhood.

Aim of the intervention

On seeing the temporary installation being dismantled, some residents began to ask why they had to give up their enjoyment of a space that was theirs while the City Council didn’t fulfil its promise of offering new public facilities therein. People of all ages, parents of children attending nearby schools and collectives of young architects came together under the name of “El Campo de Cebada” (The Barley Field) to confront the challenge of how to maintain the community’s use of the space until work began on the new facilities. They opened up a website offering information and discussion, held many meetings in the bar opposite the space, and came to agreement on a series of demands to be negotiated with the Council.They were clear about not wanting any night-time commotion or problematic uses. Neither did they envisage anything permanent that might delay the new facility or entail some alternative to the promised sports centre. Then again, officialdom raised some thorny issues. The “Campo de Cebada” was not a formally constituted association ─a process which would have taken months─ and the ceding of a public zone, receiving grants or presenting projects that were deemed adequate required a legal entity to engage in negotiation with the public administration. Furthermore, crucial points such as who would be in charge of keys, what might be considered good uses and good hours, who would be responsible for insurance, who would sign for any work and who would finance it, also had to be resolved.

However, balking and difficulties aside, everyone agreed that they were determined to explore a new model of collaboration between the City Council and the neighbourhood and, in particular, that the empty space would need to accommodate all kinds of activities that would foster social relations as well as being proposed, decided and managed as the responsibility of the residents themselves. In February 2011, in this spirit and with the support of already-consolidated neighbourhood associations, an agreement was signed with the City Council’s Finance Department, the nominal owner of the site, for the temporary ceding of the space.

Description

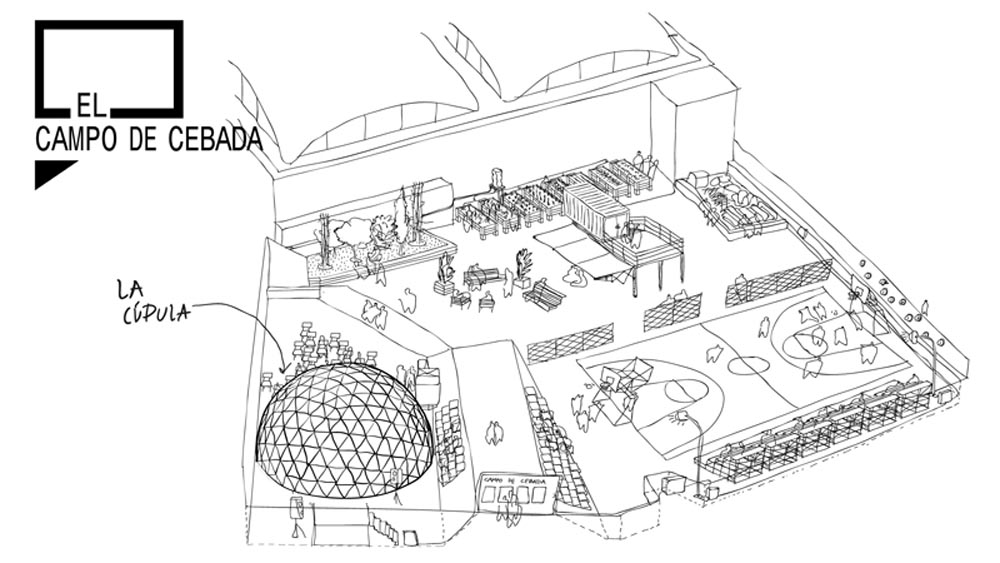

The first activities that took place in the site were weekly assemblies, from which arose specific committees for proposing, considering and approving activities. Doubts and proposals expressed by net surfers and passersby, together with information about programmed events, were displayed on the “El Campo de Cebada” website as well as on blackboards hung near the entrance to the space. The site was quickly cleaned up and equipped with basic equipment, for example water and power supplies, some sports areas with lines painted on the ground, and basketball and football goals.The grey of the cement was soon replaced by colours and graffiti produced by volunteer painters and local artists. The concrete of the ground provides children with an area for skating and riding their bicycles that is safe from cars. Street furniture was created out of recycled materials and this activity then gave rise to “handmade temporary urban design” workshops. The pieces produced are portable and versatile so that, when there is a game, they can be arranged round the edge of the playing area. The success of the local basketball team has led the residents to construct tiered seating on the bank of the ramp giving access to the site. Gardens have been planted in large boxes on wheels that can be moved around to make the most of the sun. These are, of course, the responsibility of the local residents who periodically organise courses in botany and horticulture. In order to combat the implacable heat of Madrid summers, a shelter has been devised by means of a metal structure over which large pieces of recycled fabric are placed in such a way as to cover the whole site. A container for storing tools and items of street furniture has been placed over the porch, which also forms a terrace that is used as a grandstand when there are shows and public events.

Indeed, there are a great many of these since the programme of plays, open-air cinema, lectures and concerts is dynamic and constant. One of the most refreshing items on the programme is the “Piscinazo” (Big Pool) in which several inflatable pools are provided in summer so that people can engage in water versions of tai chi, obstacle races and the “street workout”. Local festivities, traditional dance events and open-air celebrations are also held in the space. “El Campo de Cebada” even provides a space for private, socially oriented initiatives, for example twice-weekly debates involving professionals from the sphere of education, monthly “Citizens’ Breakfasts” and occasional meetings to resolve conflicts among residents.

Assessment

“El Campo de Cebada” is an experiment that has many lessons to offer for administrators, specialists and citizens. Administrators would do well to take note of its spontaneity, challenging the official channels with a committed initiative notable for its transparency, participation and social inclusion. Fully aware of its provisional status, the project has its origins in a dispute with the administration but ended up establishing with it a symbiotic relationship from which everybody gained. Moreover, its fertile, cheerful austerity has established a valuable precedent that can repeated anywhere in these times which are so replete with projects that have been delayed or abandoned as unviable.In the case of architects and engineers, specialists who shape urban spaces, “El Campo de Cebada” holds out the value of temporality. This comes in the form of a calendar reached through consensus rather than by the kind of structuring imposed by an outside entity that controls the site. Unlike what happens with so many other public spaces, which start out from a formal basis to establish physical frameworks that are supposed to bring into being certain functions, in this case use precedes form. The contents here are constantly shaping a resourceful, flexible container in an open, dynamic process in which people with technical knowhow never abandon the work. They are in partnership with the users in being part of the project and in training them by sharing skills and goals with them.

As for the local residents, “El Campo de Cebada” is a way of speaking out against indifference, proof that it is possible to shape a city together, that there is life beyond top-down urban planning. After having existed as a totally built-up site for decades, this space has gone back to being seen as a square since it now has an open-air surface available for community uses. Instead of being left as an indefinitely abandoned, inaccessible empty space, it has achieved the status of public space in every sense of the word. Everyone has been able to confirm that this condition is enjoyed in direct proportion to the extent to which the space is shared.

David Bravo │ Translation by Julie Wark

[Last update: 18/06/2018]