Previous state

The Citytunneln (City Tunnel) is newly-inaugurated public-transport railway infrastructure which has made life easier for the 87,000 people who have been using it on a daily basis since 2010. It links local, regional and international trains and crosses beneath the city of Malmö connecting the Öresund Station in the south with the old Central Station in the north.One of its most important remarkable features is that advertising has been banned in all its spaces. This measure has opened up a large number of crowded public spaces for public art. The Citytunneln administration views installation art as a strategic ally since it believes that it can actively contribute towards the well-being of its users. This, then, encourages the use of public transport and reduces traffic in private cars, effects which are fully in keeping with the Malmö urban plan which strives for economic and ecological sustainability

Aim of the intervention

The installation of works of art in the public spaces of the Citytunneln has thus been promoted for the above reasons. The project has been carried out jointly with the Swedish National Public Art Council, which supervises the quality of the works and the creative freedom of their authors. Fruit of a public competition, an installation called Annorstädes (Elsewhere) was selected to occupy the Central Station, which had to be renovated so that it would be adequately updated for its incorporation into the Citytunneln.Description

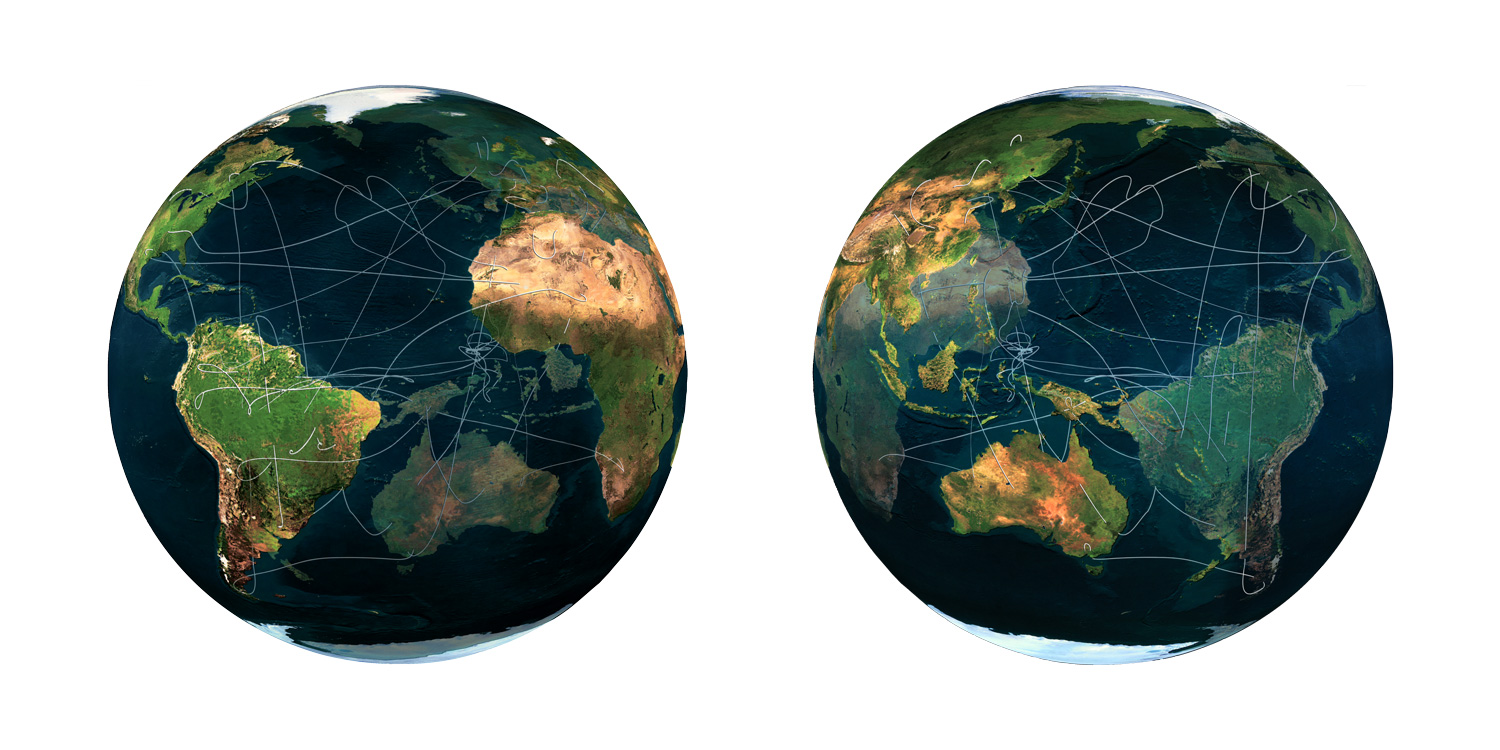

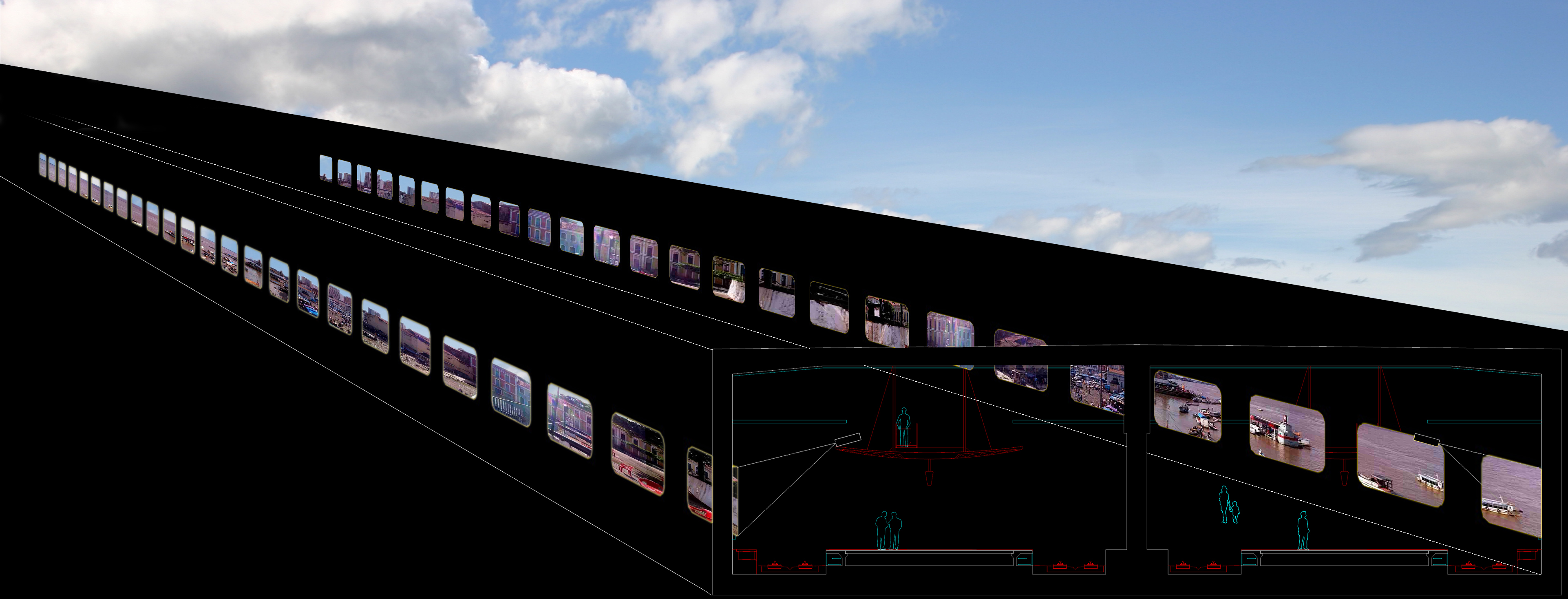

The artistic installation and the renovation of the station were conceived simultaneously and in a coordinated fashion. The artist’s inclusion in the team of architectures and engineers who planned the reforms to the station guaranteed the necessary cohesion between container and content.Annorstädes consists of a monumental representation of landscapes filmed from inside a moving train. Each of the two retaining walls that define the station in the tunnel provides support for twenty-five screens of almost five metres wide and two and a half metres high on to which the images are projected in synchrony. The resulting effect of this composition is that the screens seem to be windows of a railway carriage in movement (the length of the whole station), slowly crossing landscapes all over the world.

In keeping with municipal energy-saving policy, the projections are limited to an average period of sixteen hours per day, coinciding with the maximum flows of rush hours (rising to 37,000 out of the total of 40,000 users). Consisting of 1,300 sequences of different landscapes, they are programmed in such a way that it would take two years before a traveller taking the train every day at the same times, and observing them during a waiting period of four minutes, would see any image repeated. The movement of the images is slowed down for a leisurely, relaxing effect.

Assessment

Although installation art is often underrated as anecdotal, Annorstädes is an example of the wide-ranging beneficial effects that it can have in the urban setting. The landscapes that move through this station not only give poetic sense to the everyday waiting on its platforms for thousands of travellers but to also contributes by dissuading them from using the private car, thus attenuating the damaging effects of its massive use, for example consumption of fossil fuels and urban sprawl.For all that, perhaps one of the most remarkable benefits of Annorstädes is its explicit desire to combat the advertising assault which, from the public spaces of so many European cities urges large-scale, irresponsible consumption, generating absurd but common situations in which, for example, a bus blazons ads for cars. However the battle of Annorstädes is not only limited to replacing the advertising that was displayed in the station before its renovation. On the one hand, its authors have carefully erased by digital means any trace of advertising in the projected landscapes while, on the other, they have deliberately omitted any clue as to the origins of the landscapes. Lamented by some passengers whose curiosity has been aroused, this latter measure is also a way of avoiding tourist propaganda. It also conserves a certain degree of mystery which frequently leads to conversations arising among previously unacquainted passengers (quite an unusual phenomenon in the Scandinavian cultural context) who are intrigued about the whereabouts of the scenes.

Finally, the non-commercial spirit of the installation is reflected in the freedom with which members of the public can photograph and film the content of the projections. With a logic that is akin to shared culture, the authors and promoters of the installation celebrate the fact that the photographs and films are posted and disseminated on Internet.

David Bravo │ Translation by Julie Wark

[Last update: 18/06/2018]