Previous state

In the 1960s, the communist regime in Albania established a military zone on the north-western fringe of Tirana. The sector, bounded on the south by the Lana River and on the north by the road to Durrës, had an aerodrome with a runway that was one kilometre long and fifty metres wide. Following the fall of the regime, the aerodrome was abandoned and its strip remained as a great void mainly used for pasturing livestock while a sprawl of new construction surrounded it.

Indeed, the advent of capitalism brought to Tirana a hectic, chaotic growth to such an extent that the city tripled in area while its population increased fourfold, all of which occurred without any kind of state supervision. The legal lacunae encouraged unregulated real estate activity, informal settlements of migrants from rural areas and squatting on municipal land, for example public parks and river banks. Tirana embodied disorder and inequality as a city of streets without names, where houses without power or water supplies proliferated in a landscape bristling with parabolic antennas and air conditioning equipment, while more than 300,000 top-of-the-range cars, many of which had frequently changed hands, now gave rise to serious pollution problems.

Amidst all the confusion, both real estate dealers and shanty dwellers were attracted by the abandoned aerodrome both because of the empty space it offered and its proximity to the Durrës road, which led directly into the heart of the city in the form of an avenue. The former built high-rise housing blocks for the new middle class on the northern edge while the latter filled the southern side next to the Lana River with jerry-built dwellings. The two areas were separated by the unoccupied strip which, while it had acted as an organising principle for the adjacent construction with some functions as a kind of spontaneous public space, constituted more of a frontier between social strata than a truly shared space where meetings and exchanges might have taken place. This condition was reinforced by the invasion of the private vehicle, which discouraged any kind of appropriation of the space by citizens.

Aim of the intervention

With the coming of the new century, the Tirana City Council began to deal with the disorder that was taking over the city. Several initiatives, as the “Return to Identity” campaign, entailed the consolidation and protection of tens of thousands of square metres of public space, the demolition of a great number of illegal constructions, new paintwork for many facades and massive planting of trees. This was the background to the 2006 plan to overhaul the grounds of the old military aerodrome which, now renamed “City Park”, was to accommodate the private construction of seven thousand new homes.

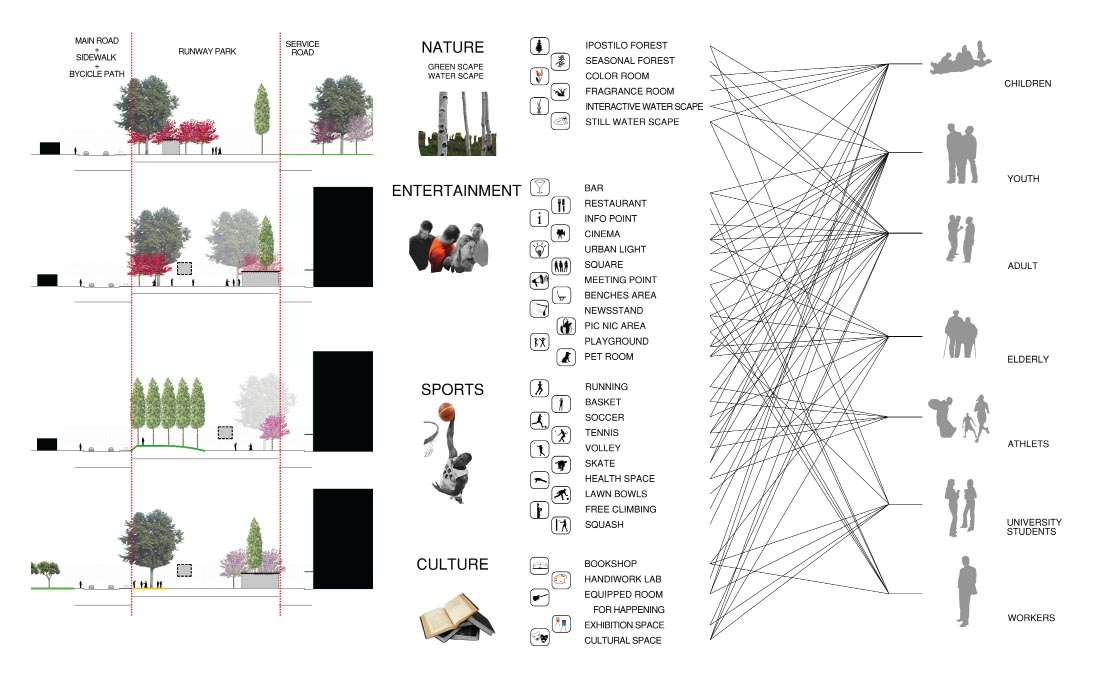

The empty space of the old airstrip was, of course, bound to play a prominent role as a structuring element for the new urban setting. With this in mind, the City Council set aside almost four million euros to transform it into a green zone called “Parku 1Km” (One Kilometre Park). The new public space was to pull together the fragmented complexity of the area by founding a new meeting place in which different uses, ages and social strata would be mingled.

Description

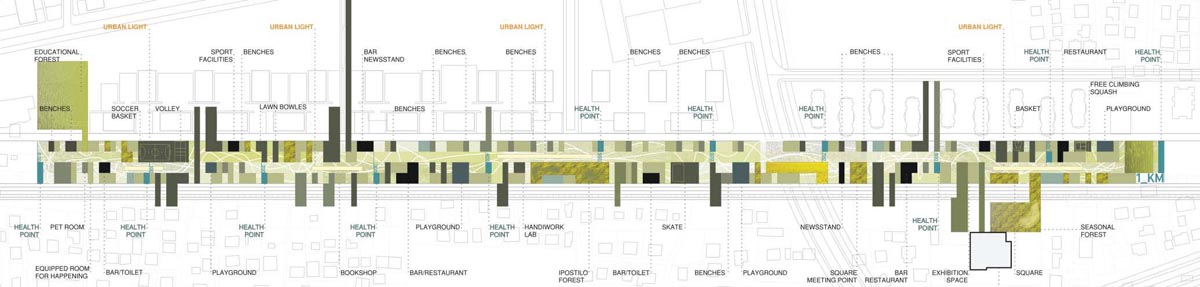

As its name suggests, the “Parku 1Km” aims to highlight the magnitude of a kilometre, the original length of the runway. It therefore offers pedestrians a lineal route through a varied sequence of rectangular sections on either side, which break it up while also providing an orderly rhythm. These plots have different dimensions and finishing touches in accordance with their particular uses. Some are sports areas, which include petanque courts, skating areas and football, basketball or volleyball courts which are protected by metal fences. Others, used as leisure areas, are planted with trees, have parterres with aromatic herbs or offer children’s playgrounds and spaces for people to walk their pets. Still others are more cultural in purpose and offer handcraft workshops, bookshops in the form of kiosks and wooden platforms equipped for concerts, dances and shows. Between these sections there are facilities including toilets, cafes and health care points. Vehicular transport has been restricted to the two-lane road running along the southern edge of the park.

Assessment

In proposing a set of plots that are so clearly aimed at specific functions, the “Parku 1Km” runs two major risks. On the one hand, it has to overcome the possibility of being too fragmentary, of losing the valuable unity that enables it to be the organising principle for the adjacent urban zones. On the other hand, it contravenes the rule whereby urban spaces bringing together a complex range of users require versatility, flexibility or neutrality.

The first danger is avoided because of the emphatic nature of the pre-existing space, the lineal spread of the runway that needed to be organised into different kinds of areas in order to break up the monotony and even inhospitable nature of its form. The second hazard, while still evident, can be justified for educational reasons. In a city that is so unaccustomed enjoying public space, priority is given to the specificity of the different areas, which are understood as something akin to domestic spaces so as to highlight the possibilities of appropriating community spaces. It is the balance between this capacity for domestication and the forceful nature of the lineal slash in the urban fabric that has enabled “Parku 1Km” to continue as a principle of spatial organisation while at once stitching together spaces that were once separated by a frontier.

David Bravo Bordas, architect

[Last update: 19/05/2023]