Previous state

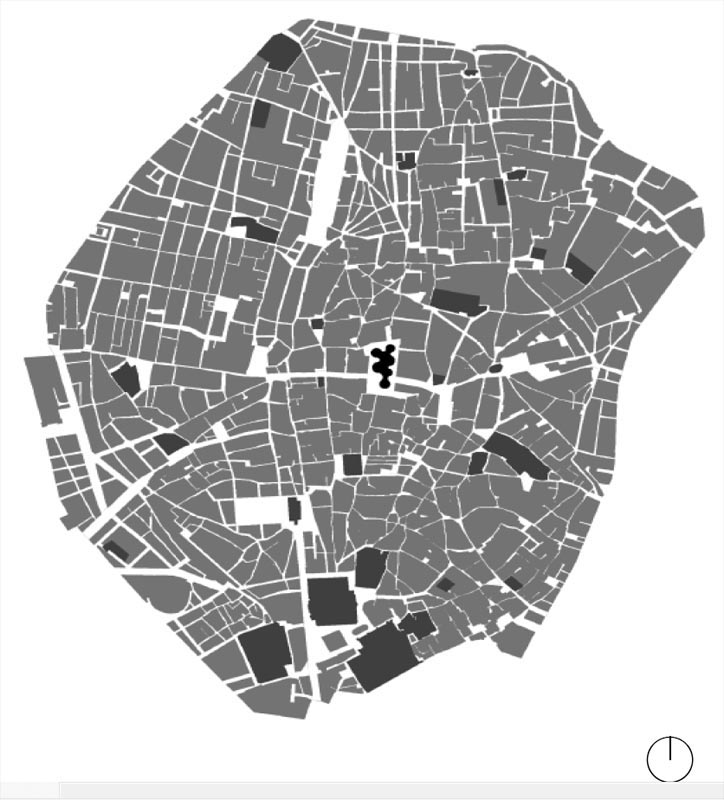

During the Napoleonic invasion of Seville, the Convent of La Encarnación (the Incarnation) was demolished to build a municipal market on its site. The destruction of the building, which was flanked by two small squares, opened up in the Alfalfa neighbourhood a large empty space which was subsequently called plaza de La Encarnación. Rectangular in shape, the square is a hundred and fifty metres long and eighty metres wide and it is located at the geometric centre of the old city. It continued to be partially occupied until the end of 1973 when the market, by then in a tumble-down state, was in turn doomed to demolition.After that, the space remained empty and surrounded by a solid barrier, to end up being used as a car park or bus depot. In 1982, when renovation work began with a view to commercial reactivation of the zone, significant finds from the Roman Era (first century) put an end to the project and converted the square into an archaeological dig. This situation could not have been more vexing for the businesspeople of a historic centre which, in recent decades, has become a major reference in the cultural routes of international tourism.

Aim of the intervention

In 2004, the Seville City Council called for entries in an international competition for ideas as to how to renovate the square and, after so long, to activate the adjoining commercial areas. The rules of the competition were clear and ambitious. Besides enabling a complex programme of uses, which included a municipal market, an archaeological museum and a public square, it was also stipulated that the project had to constitute an architectural landmark with sufficient iconic impact to create a new tourist attraction. Of the sixty-five projects received, the jury nominated by the City Council decided on “Metropol Parasol”, the most daring of all in terms of its impact on the cityscape, its technical viability and its cost, with an initial estimate of thirty-three million euros.Description

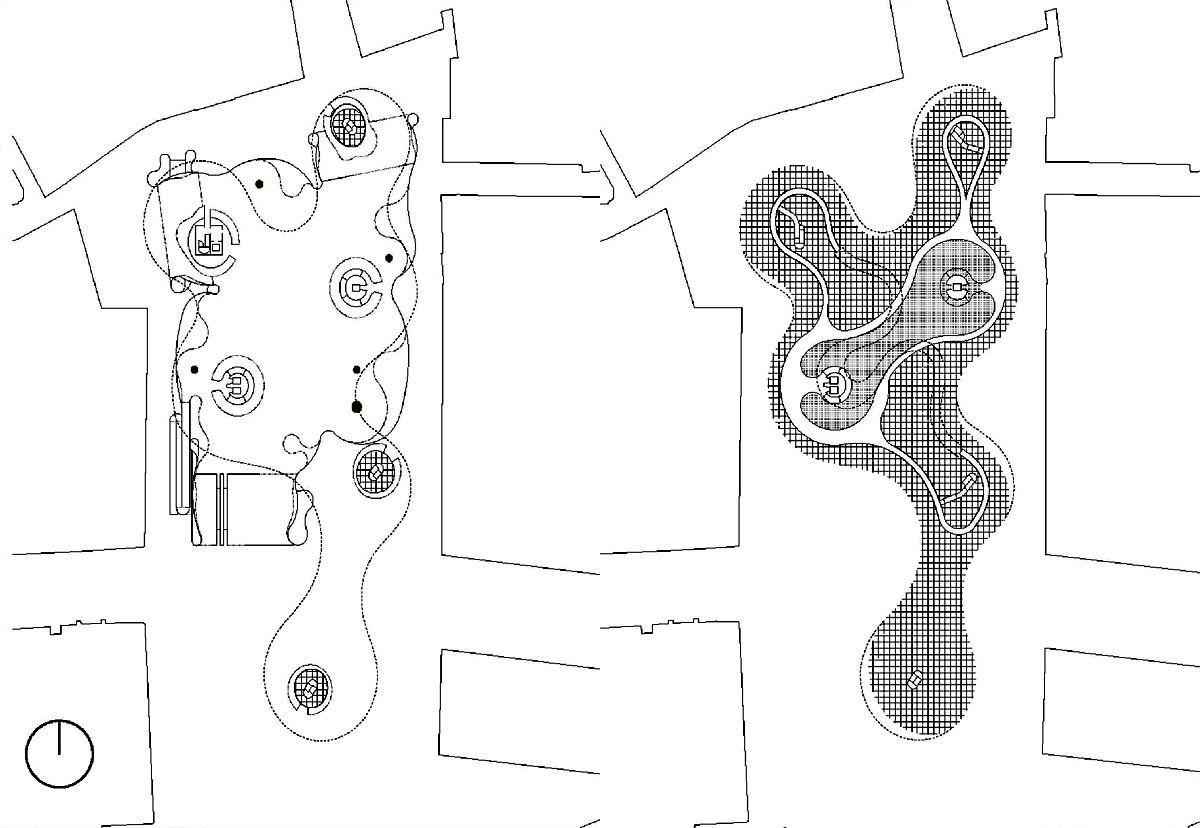

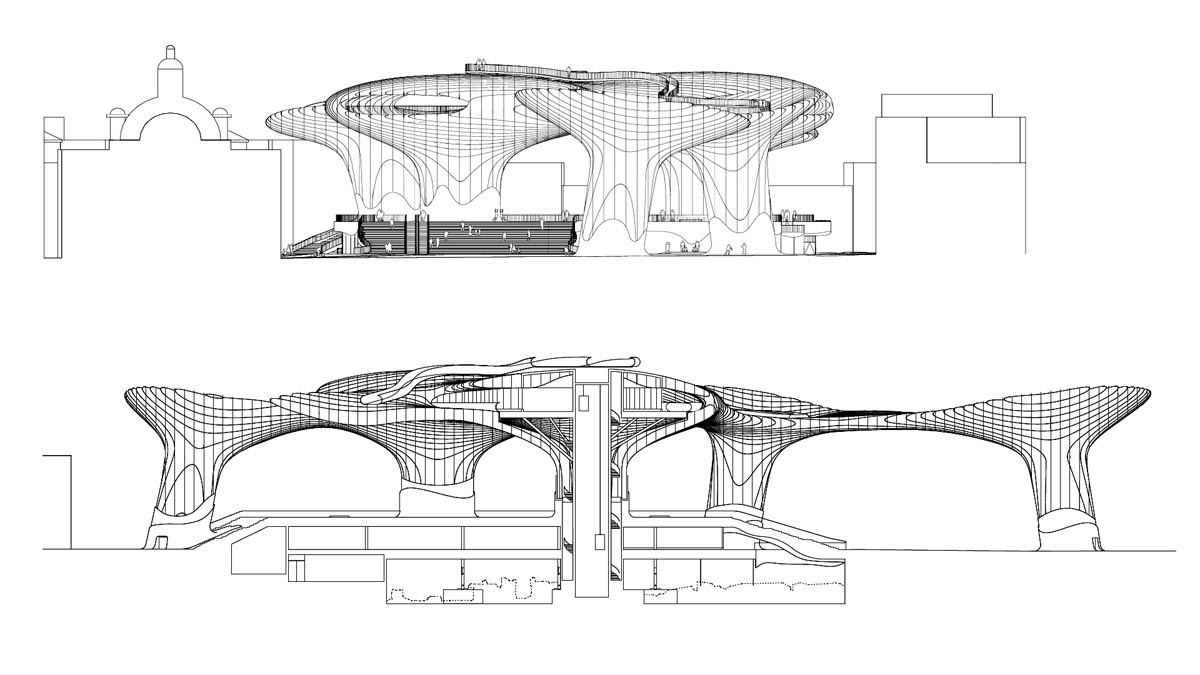

“Metropol Parasol” covers a good part of the plaza de La Encarnación with six colossal umbrella-shaped elements which, thanks to their fungiform appearance, the people of Seville have re-baptised as “Las setas” (The Mushrooms). Their caps, which are interlinked to form a single ceiling, are made up of wooden ribs set sideways and dovetailed in a bidirectional reticule. In its vertical plane, each rib presents its own particular sinuosity which, in combination with the rest, confers on the grid a wavy, voluptuous volume. The ceiling is at an average height of twenty-six metres above street level and is supported by six large cylindrical stalks in reinforced concrete.These stalks contain vertical lift shafts that connect the different levels of the structure as a whole. At the uppermost level, a walkway winds around the top of the caps and leads to a circular terrace that crowns the structure’s highest point to constitute a lookout with panoramic views over the whole of the old city. At a height of twenty-two metres, the two largest caps house a restaurant and a multipurpose space. Under the shade of the parasols there is a raised square, which is linked with the rest of the Encarnación esplanade by means of a wide stairway.

The raised square is, in fact, the roof of a shopping centre located at the level of the streets around the perimeter. Although this space is organised into small shops that invoke the stalls of a municipal market, they are low-ceilinged and their wares go beyond foodstuffs to include businesses ranging from clothes shops to catering. At a still lower level is the “Antiquarium”, an archaeological museum that displays the significant finds from the Roman era which were unearthed in the plaza de la Encarnación.

Assessment

“Metropol Parasol” has left nobody indifferent. Apart from opinions about its visual impact or its supposed condition as “spectacle architecture”, the fact is that the work took six years longer than initially envisaged and the first budget was tripled. It is not only the resulting structure that is gigantic. The economic drain it represented has ended up with a highly indebted City Council and the controversy in the media and Council meetings has also been enormous.All the pros and cons aside, part of the delay and excessive cost are attributable to the complexity of the problem and the ambition of the solution. The unforeseen costs resulting from the archaeological findings, the wish to conserve and display them, the modifications to the programme of uses, an unusual period of rain in the region, the holding of religious functions at Easter, the technical difficulties of producing a design that aimed to be innovative, and disagreements with the construction company ─which is also the concessionary that runs the lookout─ attest to the multiplicity of elements that can come together in any urban transformation on this scale.

In any case, one cannot deny that the plaza de la Encarnación has gone from being a long-neglected space to a new status as a fully-fledged symbol of the city. The “mushrooms” are a tourist attraction of the first order in Seville. More than a million people went up to the lookout the first year it was opened and it has many staunch defenders among the Alfalfa businesspeople. Even the “Indignados” movement chose the site for its camp in 2011 but whether it was for its representative standing or seeking its shade, which is not to be underestimated in the Andalusian capital, is anybody’s guess.

David Bravo Bordas, architect

[Last update: 02/05/2018]