Previous state

London’s famous East End, the most populous and ethnically diverse set of neighbourhoods in the city, has always been closely related with water. It spreads northeast from the City ─its former walled area─ into once swampy territory separating the Thames from the River Lea. In the twelfth century, Matilda of Scotland had a bow-shaped bridge built over the latter, which then gave rise to the name Stratford at the Bow, where the meaning of “Stratford” in Old English was “paved road crossing a ford”. Stratford and Bow are two separate districts nowadays, divided by the Bow Back Rivers, part of the Lee Navigation canals which run through the long green belt of Lee Valley Park. Around the sixteenth century, when the River Lea ─sometimes called River Lee─ was one of the main routes by which grain was brought into London, the city was authorised to open up this system of navigable waterways so as to drain the marshes, and to equip them with locks, water mills and towpaths.Over the years, the zone filled up with industries, infrastructure and suburbs, as a result of which it became increasingly complex. In the twentieth century, when navigability no longer had a strategic character, many canals lost their importance and fell into disuse. Such is the case of Bow Creek which, between Three Mills Island and London’s Olympic Park ─the main site of the 2012 Olympic Games─ ended up hidden beneath the slab of a roundabout formed by the meeting of two main roads at different levels. The lower one is the A12, which skirts the right bank of Bow Creek forming an underground tunnel, while the upper one is the A11, a radial viaduct that runs into Stratford High Street on the northern bank, and into Bow’s one on the southern side.

Apart from covering a section of the canal of some eighty metres in length, giving it a gloomy marginal appearance, the construction of the road junction meant cutting off its towpath, a track of about forty-five kilometres running alongside the canal all the way from the County of Hertfordshire to Limehouse, next to the Thames. The cyclists and pedestrians using the path on the left bank of the canal were obliged to leave it when they came to the City Mill River branch. At this point, they had to cross it by an angled footbridge leading up to the upper A11 level. After negotiating its five traffic lanes, they still had to get to the opposite bank of Bow Creek in order to continue along their way. Furthermore, on this bank, a neglected riverside forest was concealed behind some large advertising billboards facing the A12.

Aim of the intervention

In 1998, Leaside Regeneration was established, this being a foundation comprised by public organisms and local entities which sought to renovate the Lea Valley and its urban environs. Some years later, and now with the involvement of British Waterways ─the authority responsible for navigation on Great Britain’s rivers and canals─, a plan was drafted with a view to improving the built up surroundings of Bow Back Rivers. This included the creation of a series of interconnected public spaces along the river banks. The proximity of the Olympic Park and the urban density of the sector, together with plans to build new residential complexes in the zone meant that the section of the river located near the A11 and A12 meeting point was to become a strategic part of the project. Besides establishing continuity of the path for cyclists and pedestrians, it was necessary to rescue the hidden values of the area so that the residents of Stratford and Bow could recover their traditional relationship with the water.Description

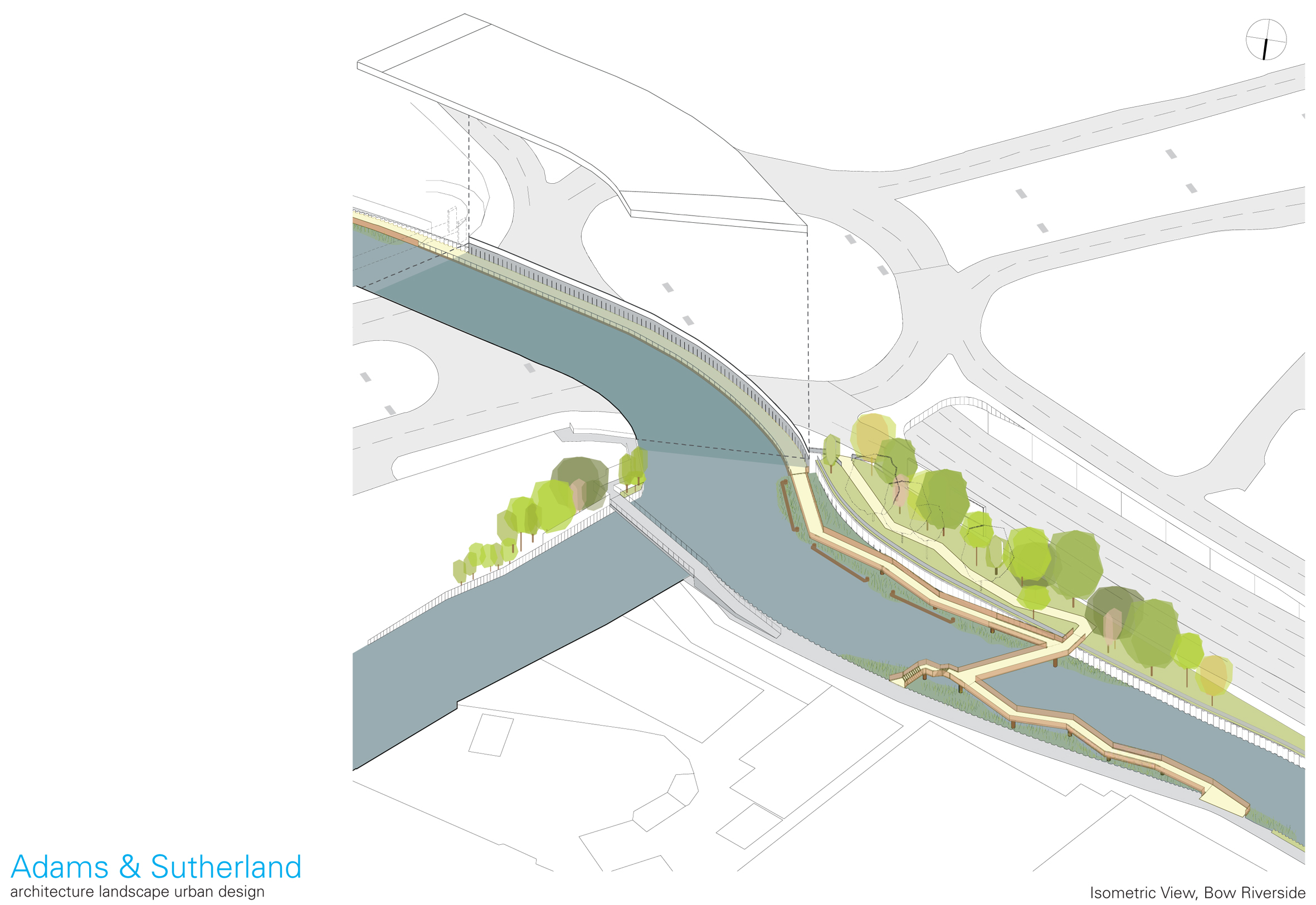

The intervention negotiates barriers and gradients by means of a varied sequence of riverside itineraries that come together in a unitary complex reserved for pedestrians and cyclists. Upstream, before Bow Creek is concealed beneath the slab of the roundabout, a new bridge has been constructed, crossing the canal at a sufficient height for it to be navigable. In order to to permit access to the lower level of the two banks, the bridge bifurcates at either end by means of a ramp and a set of steps. On the left bank, the ramp takes pedestrians coming along the towpath from the north, while the stairway goes up to the existing footbridge crossing City Mill River and leading to the A11. On the opposite bank, the stairway brings to a track that winds through the old riverside forest up to the level of the A12, where the billboards have been removed. The ramp on this side gives access to the section of the canal that is covered by the roundabout.The bridge, the two ramps and both sets of stairs are supported by lattice girders resting on metal pylons with cylindrical shafts. The girders rise on both sides above the deck of the bridge in such a way as to form its railings. However, they are only visible from the deck as they are covered by lattices of upright wooden slats, which allude to the verticality of the reeds and the sheet piling along the edge of the canal. The lightness of these lattices and the fact that the ramps zigzag along the banks, give the new structures a less imposing appearance. The zigzagging also makes it possible to reveal, between ramps and the canal banks, interstitial spaces of peaceful water where new gabions planted with reed beds have been set.

Downstream, in the roundabout underpass, a new footbridge fixed to the pre-existing concrete wall gives continuity to the right bank. Either by day or night, the lighting set into its railing combats the darkness with its welcoming luminosity in different colours playing on the surface of the concrete and the water. When it leaves the covered section, the footbridge comes to an end on Bow Free Wharf, thus enabling people to keep moving along the towpath in the direction of the Thames.

Assessment

The Bow Creek refurbishment has reunited a series of disconnected points in a strong and lasting bond. With delicate skill it has stitched together discontinuities in both spatial and temporal senses. In terms of space, it has combined the territorial and architectural scales by establishing connections between interrupted paths, separate banks and different levels, while, in the temporal regard, it has synchronised canals and motorways, different kinds of transport infrastructure from different historical periods which previously overlapped without meeting. With this contribution towards rescuing the memory of the canals that were so characteristic of the East End’s past, it has paved the way to future interventions at other points in the aquatic network. Accordingly, it has not only created spaces for movement but it has also founded a place. A bucolic setting with an exceptional relationship with nature in the heart of social and urban fabrics which will certainly appreciate the benefits of its presence.David Bravo Bordas, architect

[Last update: 02/05/2018]