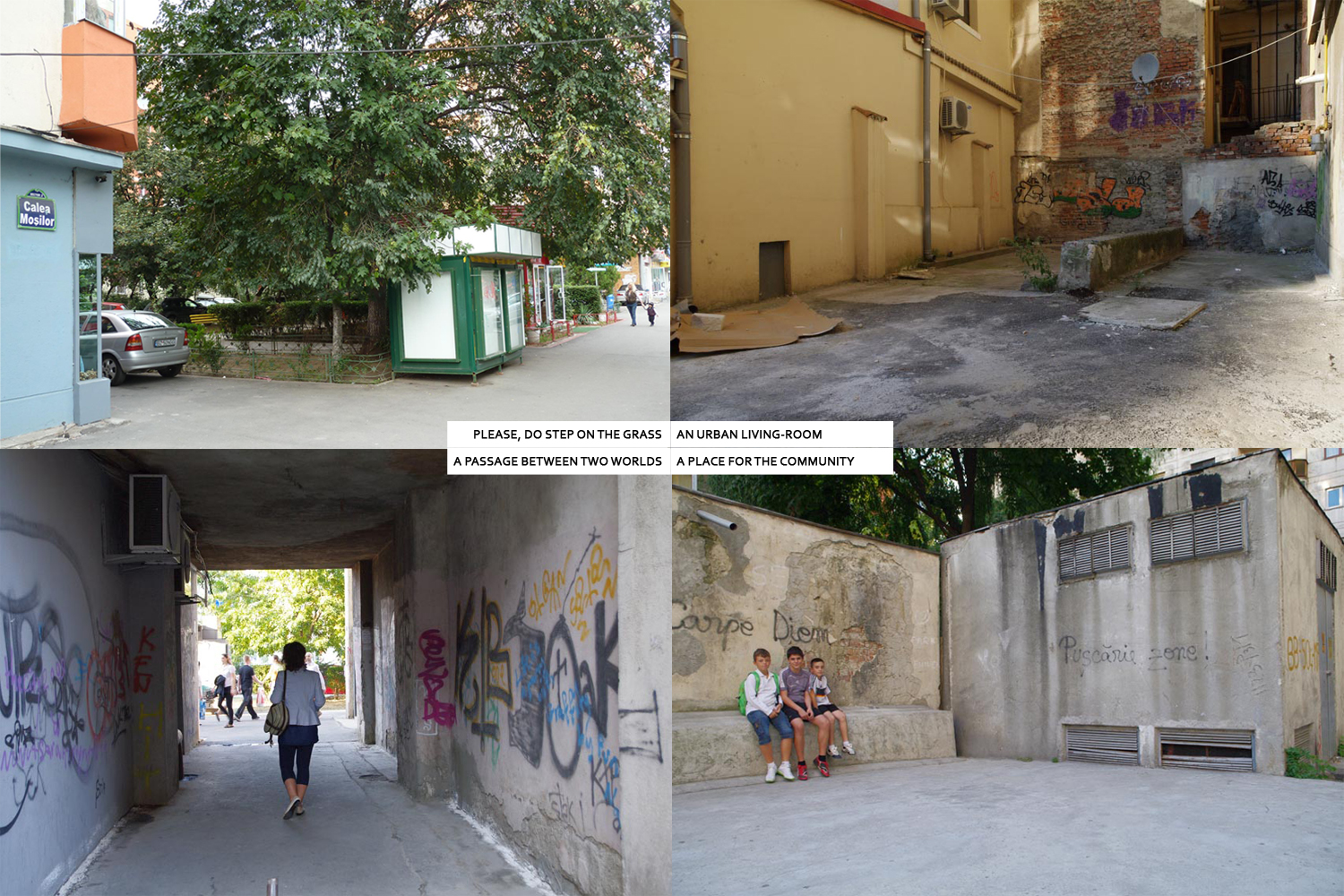

Previous state

In the early nineteen-seventies, Nicolae Ceaușescu introduced ‘Systematisation’ into Romania, this being an urban planning programme that aimed to abolish differences in the levels of development between country and city. While its beginnings were limited to rural areas, where entire villages were demolished and their inhabitants forcibly displaced into newly constructed urban zones, the programme was eventually carried out in Bucharest after 1980. Although it was seriously damaged by an earthquake in 1977, the city was not rebuilt. Rather, one fifth of its historic quarter (eight square kilometres) was razed to the ground and replaced by large reinforced-concrete buildings.Some of the oldest neighbourhoods disappeared to make way for the Centru Civic (Civic Centre), an administrative sector presided over by the world’s second largest building after the Pentagon, the People’s House, which now houses the Romanian parliament. In other cases, the ravages of Systematisation extended the length of the city’s main arteries, including Calea Moşilor, a radial road that joins the centre with Obor Square in the northeast. Although the street has a narrow, winding section typical of an old city centre, it spreads out into the wide, rectilinear form of an avenue beyond that. It is in this second section, which is almost a kilometre and a half in length, that the programme replaced the original nineteenth-century frontage with long rows of public housing blocks.

In 1989, the Systematisation was abruptly interrupted by the fall of the regime. The residential blocks of Calea Moşilor had by then been completed but nothing had been done about the ill-defined fragmentary nature of the spaces behind them, and hence there was no continuity with the pre-existing urban fabric. The coming of capitalism did nothing to improve matters. Rampant individualism, spurred on by deregulation of the market and unhappy memories of forced collectivisation eased the way for privatisation of public housing, in which 70% of Bucharest’s population still resides. Meanwhile, the burgeoning, unchecked presence of private vehicles and total neglect of the publically-owned zones only compounded the dreariness of a cityscape forged by socialist housing blocks.

Aim of the intervention

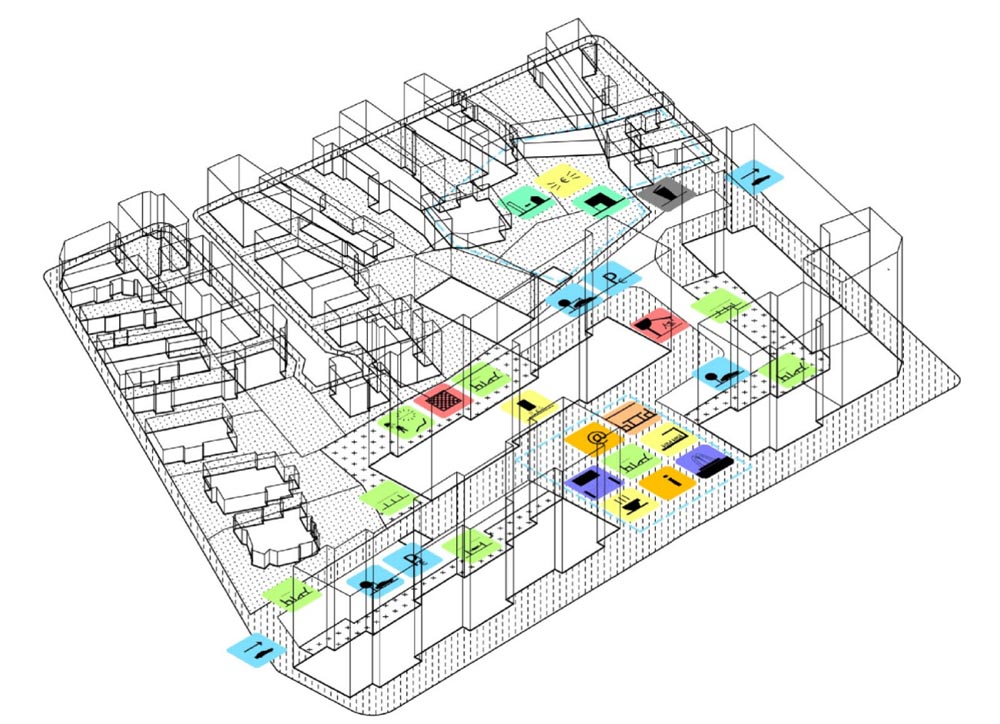

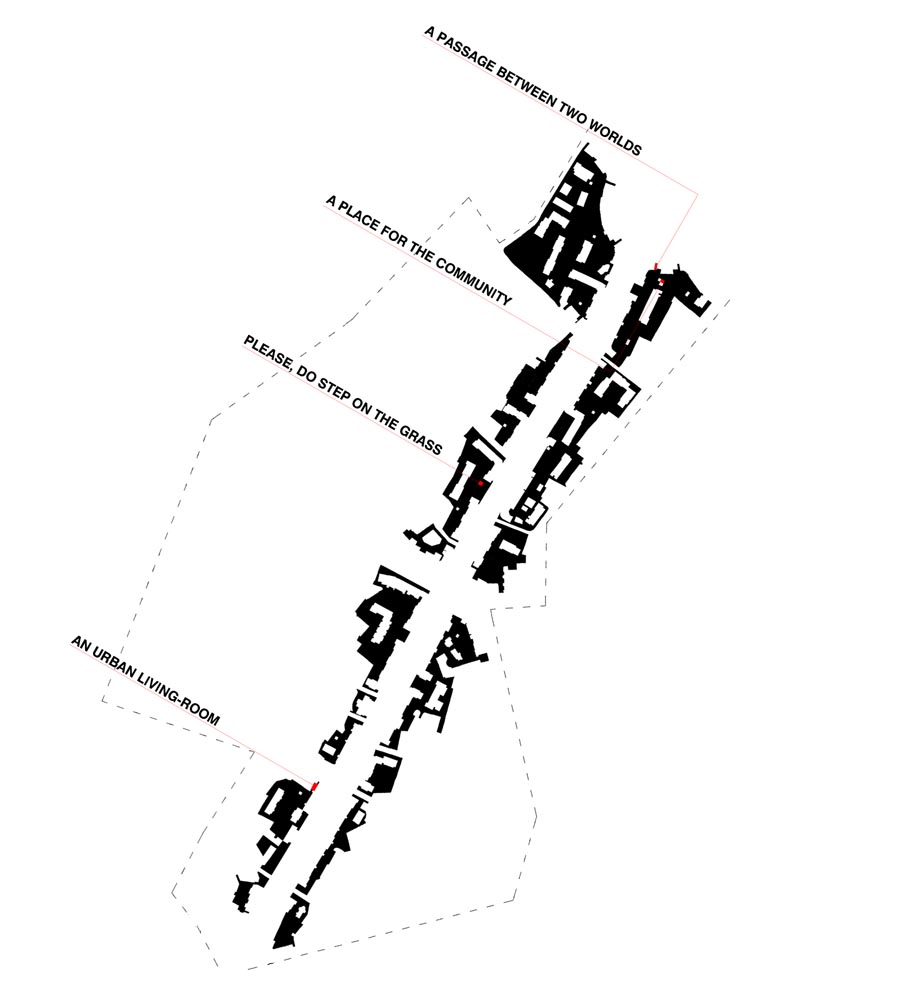

In 2009, several activist groups and professionals from different studios, both Romanian and foreign, joined forces with a view to changing this situation. Spontaneously and without any official commission and wishing to call attention to the need to confront the problems arising in public spaces adjoining the socialist blocks all around the city, they conceived an initiative they called “Magic Blocks”.In the first stage, they managed to raise 21,000 euros of public and private funding in order to carry out, with the support of local residents, four temporary projects in specific spaces of Calea Moşilor. Halfway through the initiative, with the necessary publicity afforded by publications and exhibitions, it might be possible to extend the debate on the need to promote similar work of a more definitive and structural nature. The Calea Moşilor zone was to function as a prototypical experiment that would offer an example for the whole city. In the long run, it was necessary to overcome widespread scepticism regarding public action and to make people aware that, besides being inescapable, the collective condition of a city can be something that is not imposed and accepted freely and in a positive spirit.

Description

The four interventions carried out so far have tackled the greyness of the socialist blocks by superimposing the warm appeal of the colour orange. The first, located at the northern end of Calea Moşilor, is called “A Passage between Two Worlds”. In this case, orange paint was applied to the walls and ceiling of a dingy narrow passageway running through a housing block to connect Obor Square with the old quarter behind the block. The paintwork, which leaves intact some rectangular sections of the original wall, thus framing the pre-existing graffiti with the new colour, brings dignity to the space while transforming it into something akin to an art gallery that expresses the superimposition of historic layers characterising the urban palimpsest.A line of orange dots starts from the ground of the passageway and, beckoning the walker to follow it, leads into the neighbourhood behind it, where it has to find its way through a sea of haphazardly parked cars. It ends up at the second intervention, which has been called “A Place for the Community”. This is in an interstitial area separating two transformer stations. The space, previously a neglected wasteland, has now become a meeting point which is halfway between a sports area and a leisure space. The ground here has been painted orange and a bench in the same colour has been installed next to a metal fence. Protean in shape and cheerful in appearance, the bench invites people to sit down for a bite to eat or for a good long chat.

The third intervention is to be found about half a kilometre southwest of here, on the other side of Calea Moşilor. As suggested by its name ─“Please Do Step on the Grass”─ it is a way of speaking out in favour of the community’s appropriation of a parterre surrounded by a metal fence. This has been equipped with street furniture, once again painted orange, which serves both as a seat and steps from which to jump on to the grass. Inside the parterre is an orange chair with a rectangular block that can be used as a table or a footrest.

Finally, the fourth intervention is called “Urban Living Room”. It is half a kilometre down the road in a corner shaped by the flank walls of two old houses in the shadow of a housing block. A large gravel-filled box has been installed here as a playing space. Chairs set along the edge give it the appearance of a rug in a living room. Since they are recycled, all the chairs are different but they have been painted in the same bright orange. Their legs have been sawn off in order to set them atop a formerly existing low stone wall. A frame hanging on the flank wall and a coat stand placed beside it give a feeling of homely warmth to the space. Like the chairs and the edges of the gravel-filled box, they too are orange.

Assessment

From a materialist point of view, the “Magic Blocks” might be judged as a limited, symbolic response to a problem that is both huge and serious. Nevertheless, the bright, optimistic orange unifying the interventions does more than point out problematic areas. It also presents them as spaces of opportunity. Indeed, beyond the generosity and voluntary initiative of the promoters, part of the value of the “Magic Blocks” is to be found in the possibility that they could be the germ of a major, large-scale project, which should always have the support of the population.At the same time, they have an educational value. It seems that the interventions have been well received by residents, except for “Urban Living Room” which, because of its idea of domesticating the street, was mostly interpreted as an invasion of privacy. Whether they are accepted or not, these projects suggest the extent to which the need for meeting places still goes hand-in-hand with mistrust of anything coming under the heading of “public”. They also offer a good lesson: in a city, the individualism of indifference can be as disastrous as anti-democratic policies imposed from the top down.

David Bravo │ Translation by Julie Wark

[Last update: 01/12/2021]