Previous state

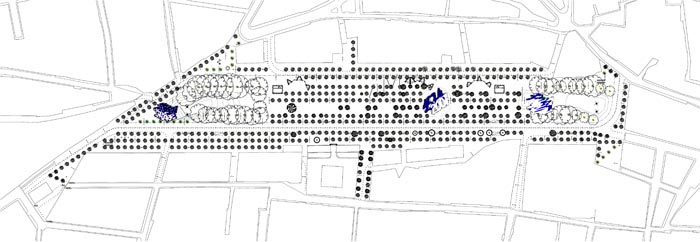

The Laguna de la Feria was a lesser branch of the Guadalquivir River to the north of the city walls, lying between the present-day neighbourhoods of La Macarena and La Feria. In 1574, the Count of Barajas had these swamplands drained in order to create in the space a tree-lined walk called Alameda de Hércules. Almost half a kilometre long and sixty metres wide, this formidable elongated urban square is the most extensive public space of the old city today. It was conceived as a trio of parallel paths flanked by rows of poplars and running longitudinally north-south along the old lagoon’s watercourse. A number of beautiful fountains were installed in the central section, these supplying the population with water from the Fuente del Arzobispo (Archbishop’s Spring), while the finishing touch at its southern end was a pair of columns taken from a Roman temple built in honour of Hercules on the site now occupied by Mármoles street. The columns were crowned with two statues by the sculptor Diego de Pesquera. One represents Hercules, the mythological founder of the city, and the other Julius Caesar, who ordered the construction of its first walls.Since coming into being, the Alameda de Hércules has been renovated several times. In 1764 three new fountains were installed, the trees were replanted and the first columns were complemented with a new pair situated at the northern end, this time crowned with the statues of two lions sculpted by Cayetano de Acosta. In the revamping of 1876 the pedestals of the four columns were enclosed with bars and trenches while, in 1936, the two lateral thoroughfares were opened up to the circulation of vehicles and two new transversal roads were introduced, dividing the walk into three sectors. In 2001, two neo-romantic drinks stalls were installed. As a result of this series of partial and rather haphazard interventions, some more felicitous than others, the walk ended up losing its unitary character and initial splendour. The ground was covered in the ochre clay that is used in bullrings and that tinges many Andalusian public spaces with its characteristic earthy yellow tones. However, without assiduous maintenance, it is also muddy in winter and dusty in summer. Many of the poplars were ailing or dead and the deterioration and fragmentation of the space gave rise to confusion in its uses with chaotic occupation of some of its areas by untidy bar terraces or badly-parked vehicles.

Aim of the intervention

In 2004, the municipal office for citizen participation created a commission which, with the slogan “the poplar-walk you like”, set about collecting the requests of the citizens of Seville regarding this highly-emblematic public space. The people’s ideas were collected in a programme of needs that enabled the Council’s urban planning department to call for entries in an architectural competition to regenerate the walk, adapt it to the needs of today’s city and give it back its lost representativeness. Beyond this first campaign, civic participation continued with the development of the project that was selected and in the course of the subsequent work.Description

As part of the project, the depleted tree population has been boosted with five plane trees and three hundred and fifty hackberry trees, a species that is particularly favoured by the municipal parks and gardens service owing to its ability to withstand the rigours of summer in Seville. With its fast growth rate it is tall and leafy within a few years, offering shade to the passer-by. The older trees in the central walkway have been left on the understanding that as they disappear, the space separating the two pairs of columns will become increasingly clear until each pair can be seen from the other.The ground has been paved with a specially-designed flagstone finished with an ochre layer so as to resemble the pre-existing clay. Thanks to their double-rhomboid form, the pieces fit together in a zigzag, thus easily adapting to the gentle topographical undulations. This has made it possible to free the columns of their ditches and bars and to introduce a subtle downwards slope in the surrounding paving, which now brings them into the scheme, uniting them from the level of their bases. Most of this surface is now exclusively for pedestrians, except for the two lateral roads where the circulation of vehicles has been reduced to the minimum. The same paving covers pedestrian and vehicular traffic zones alike, with the latter indicated by concrete markers in the same colour of ochre emerging from the paving as if they were vertical extrusions of a series of modules consisting of six paving stones.

At both ends and in the centre of the walk three fountains have been installed, these constituting spouts set into the ground sending up vertical sprays to the delight of children, or misty clouds of atomised water to cool the atmosphere. Around the fountains, the ochre-coated paving stones are replaced by pieces of anti-slip stoneware. While they are equal in form, size and layout on the ground, they are finished with blue or white enamel, colours that traditionally characterise Seville’s fountains. These enamelled pieces sketch out on the ground large-scale designs that draw attention to the presence of water. That of the central fountain shows two sizeable numbers, 1574 and 2007, referring to the year the Alameda de Hércules came into being and the year envisaged for the finalisation of work for this most recent reconditioning of the walk.

New drinks stalls now join those installed in 2001, toning down their unmistakable presence without contradicting them. They endorse the neo-romantic style of the earlier constructions with a touch of irony, although they are smaller and open out like folding screens defining the areas where the tables and chairs of their terraces are to go. The stalls are protected from the sun by large seven-metre-high pergolas made of vertical concrete supports in the form of a T from which are suspended light aluminium panels painted in white, blue and yellow. Beneath the pergolas and near the drinks stands are benches in yellow-dyed prefabricated concrete.

Close to the columns at the southern end is a three-faced clock supported on a steel pillar in the form of a truncated pyramid and respectfully inclined so as not to compete with the vertical thrust of the neighbouring columns. Along the two lateral roads are rows of double-arched street lights, each pair curving in opposite directions. A pneumatic garbage collection system has been installed underground, while the sewage system has been renovated along with the water, gas and electricity services.

Assessment

The Alameda de Hércules has recovered its former dignity through an intervention that, without renouncing an imaginative use of contemporary language, has striven to discover and understand the history of the place. This effort has made it possible to resolve problems of both past and present. In some cases, they are perpetual problems, intrinsic to the nature of the setting, for example the severity of the Sevillian sun. If the response was once the shade of poplars, today, when there are only a few tall trees left and the new ones have not yet grown sufficiently, the sun is counteracted by high pergolas that enhance the representativeness of the setting. If once its heat was mitigated by means of graceful water spouts fed by the Fuente del Arzobispo spring, it is now cooled down by means of water atomisers surrounded by the large drawings that can clearly be seen on the satellite maps that citizens increasingly consult on Internet. In other cases, the enduring errors from the series of previous interventions have been embraced with ironic tolerance. The neo-romantic drinks stalls from the renovation of 2001, for example, have been integrated and diluted within the project as a whole instead of being removed at great expense.It has also been necessary to reappraise appealing but unviable options. The new paving stones have replaced the characteristic spread of ochre-toned clay, conserving its colour, ductility and continuity but dispensing with its lack of consistency, the mud and the dust. The fact that the paving stones adapt to all the different situations, for example pedestrians-only zones or the vehicular thoroughfares, has endowed the space with a much more unitary feel. Thanks to the topographic adaptability of their layout, they have freed the walk of architectural barriers and obstacles such as fences and fountains, thus making it a suitable venue for crowd-pulling events. However, thanks to the expressiveness of the blue and white designs that signal the presence of springs, the space has gained in unity and versatility instead of being rendered characterless.

David Bravo Bordas, architect

[Last update: 02/05/2018]