Previous state

Located near the unstable border between Islamic and Christian realms, the city of Huéscar changed hands seven times between the thirteenth century, when it was founded, and the fifteenth century, shortly before the Catholic Kings established their peninsula-wide hegemony. With such a degree of insecurity, defending the city required vigilance of the surrounding territory. The old “Torre de Homenaje” made this possible until 1434 when, during the penultimate Christian conquest of the city led by Rodrigo Manrique, its upper structure, mainly of hardwood, was completely demolished. Nothing was left standing except its one-storey-high stone and adobe base which, with the passing of the years, lost its monumental character to be converted into a dwelling and thus absorbed as just another building in the urban setting. There is not enough left of the ruins today to give any precise idea of the dimensions and form the tower might have had.Aim of the intervention

Although these incognitos made faithful restoration of the original building impossible, in 2000 the Department of Culture of the Government of the Autonomous Community of Andalusia decided to go ahead with a project that would recover the tower’s monumental nature and restore its dual function as watch tower and landmark.Description

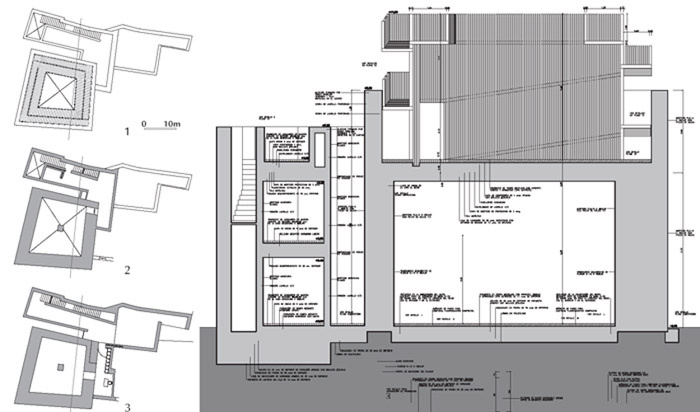

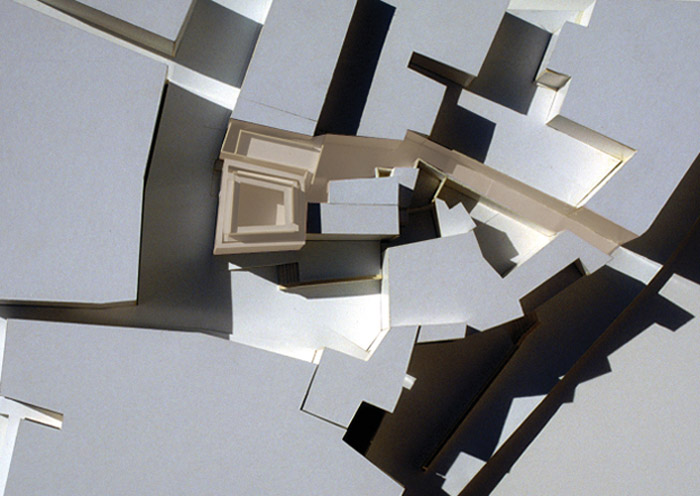

The "Tower of Homage" consists of two constructions with ground and upper floors, separated by a passage just over a metre wide and joined only at one end. The lower, L-shaped building is coated in white mortar, like the neighbouring houses to which it is attached, and it has an auxiliary function. The other, almost twelve metres high, on a square base measuring twelve by twelve metres, is a corner building, practically free-standing and with a much more monumental air.The ground floor of the main building consists of the remains of the original tower: four walls of over a metre thick coated in limestone mortar. These walls define a closed room of more than five metres high with a central pillar. A lighter construction of timber battens has been raised over this floor, evoking thus the archetypal medieval palisade. Sustained by a structure of post-tensioned wooden pillars and beams, this tower section is constituted by two ramps coiling around a central courtyard to give access and exit on to the roof-terrace lookout from which it is possible to see the rooftops of Huéscar and the horizons of the surrounding territory.

Assessment

Fortunately or unfortunately, on this occasion restoration could not mean reconstituting or consolidating an original form, since this had been lost in the oblivion of the ages. Hence, six hundred years after its destruction, the project reinvented the form of the tower in a way that was both respectful and frankly contemporary, restoring to it only its original meaning and function. Before constructing it anew, it was necessary to re-project it. This, then, is an abstract, non-figurative restoration that has successfully made the most of the symbolic force of the old monument now freed from the tyranny of a pre-existing form. This freedom has meant that the project comfortably establishes a dialectical, synchronic interplay between past and present.In this dialectical relationship, the physical and historical weight of the base formed by the walls of the original tower is contrasted with the lightness and contemporaneity of the new wooden structure that, in turn, takes one back to the typical military palisade. Again, in the layout of the pair of buildings that form the new tower, an interesting duality is established between the two main features of the city: the monument and the urban landscape. While the main building – high, free-standing and on a corner – stands out significantly as a monument, the auxiliary structure – semi-detached, flat and whitewashed like the neighbouring structures – expresses anonymous, harmonious solidarity with the landscape of the urban setting.

Also dual in nature is the newly-recovered public function in which one looks out from, and looks at the tower: it is at once a landmark, an orienting signal that gives a collective sense, and also a lookout that offers citizens a panoptic view of their city and its surrounds. Once again one finds this dialectic of the gaze, of seeing and being seen, in the adornment of the wooden battens of the palisade which, like a slatted blind or lattice offers a fretworked view of the exterior while making it almost impossible to discern the silhouettes moving inside. Finally, the ascending route up to the lookout offers the most dramatic expression of the tower’s visual dialectics when, immediately before bestowing its horizontal panorama over the city and its general setting, it confines one in a patio that denies any view of the horizon, thereby imposing the verticality of the Axis Mundi.

David Bravo Bordas, architect

[Last update: 02/05/2018]