Previous state

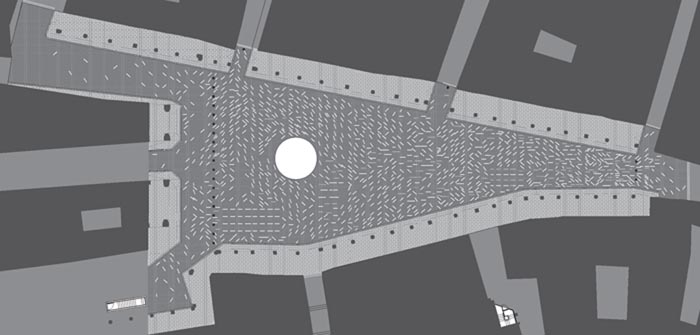

True to the strategies of defence that prevailed in the Middle Ages, Teruel grew around the peak of a hill and was surrounded by a wall. Topography thus dealt with the problem of security but also posed the problem of ensuring enough drinking water for the population within the walls, which were frequently under siege. The solution was found in the 14th century with the construction of two underground tanks that collected and accumulated water channelled from the rain that infrequently fell upon the city. Known today as the Aljibe Somero and the Aljibe Fondero, these are large underground cisterns of similar dimensions – each of almost a hundred square metres – and covered with brick vaults. They functioned as tanks until well into the 19th century, after which they began to be used as rubble dumps and, during the Spanish Civil War, as shelters. They are located under the former market square, the centre point of the urban fabric that received the water running down from the city’s highest neighbourhood, the Jewry, and then distributed it to other parts of the city on the different slopes of the hill.With a pronounced slope dropping in a southerly direction, the square has a triangular perimeter, defined by the streets running into it along the lines of water drainage, and is completely surrounded by a portico beneath which are numerous shops. It is officially known today as Plaza Carlos Castel but popularly called Plaza del Torico because of the fountain that presides over it, dating from 1858 and distinguished by the statue of a small bull (torico) standing on a column. Among the beautiful buildings that comprise its three facades are two exquisite examples of Modernism, the Casa del Torico and the Casa la Madrileña, both of them work of the Tarragona architect Pau Monguió i Segura. Until quite recently and despite its heritage value, dynamic character and central location, the square was invaded by vehicular traffic. The lighting did nothing to draw attention to its architectural quality and the paving urgently needed renovation.

Aim of the intervention

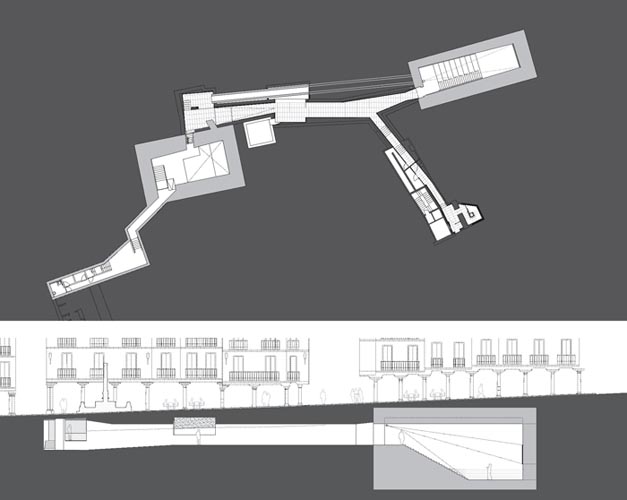

Thanks to economic assistance from the Ministry of Public Works, the Aljibe Fondero, located in the southern end of the square, was recovered in 2003. This made it possible to open it up to the public and include it among the wide array of elements of the historic legacy that the city has recuperated in recent years. Four years later, the Diputación General de Aragón (Regional Government of Aragon) decided to extend the project of reclaiming the city’s heritage to the Aljibe Somero, which was to be connected with the other tank and with the Plaza del Torico, the project involving an investment of over six million euros.Description

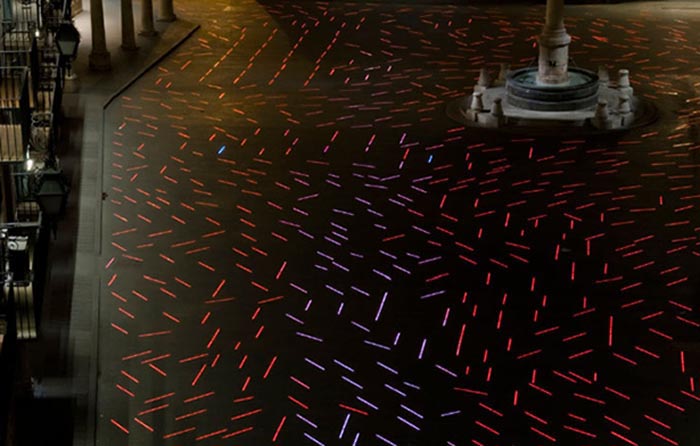

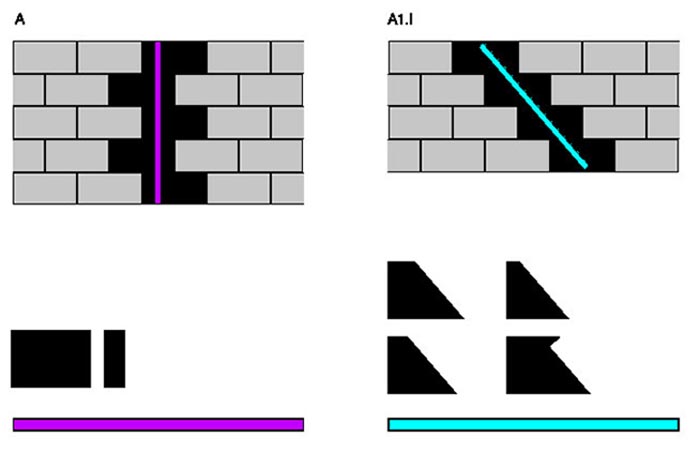

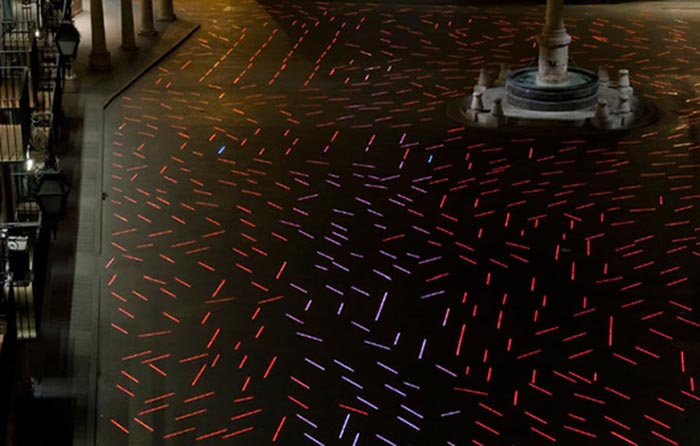

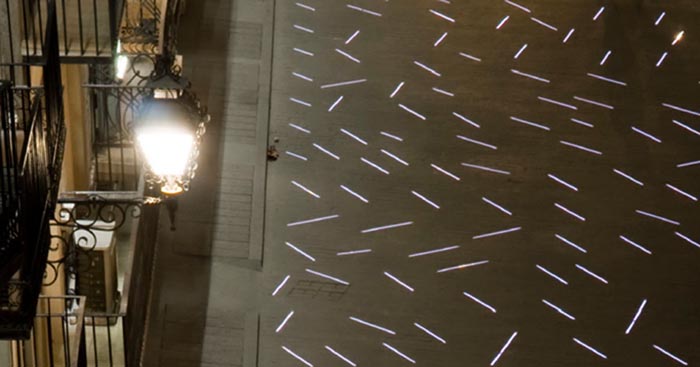

Beneath the square, the intervention has enlarged the area open to the public – which formerly consisted only of the Aljibe Fondero which, as its name indicates, is deeper than the Aljibe Somero – to a surface of more than four hundred square metres completely paved in natural stone. Access to this space is by way of two stairways at the foot of the mausoleum in the adjacent Plaza de los Amantes and a passageway connects the stairways with the Aljibe Fondero, in the south of the square. A new tunnel has been opened up to join the two tanks, leaving visible some sections of the “Albellón”, a parallel pipe which was used for drainage. At the Aljibe Somero there is wood-finished tiered seating so that groups of visitors can watch an audiovisual presentation of the city’s heritage showing, in particular, its subterranean water-related routes.At ground level, the paving of the square has been replaced with basalt slabs, some of which have been expressly designed to contain long cavities of different orientations. This has made it possible to inlay, the length and breadth of the square, a total of 1,230 lighting elements consisting of strips of electroluminescent light-emitting diodes (LED). The lighting strips trace on the dark basalt paving a scattering of luminous segments that, by means of varying their orientation and density of grouping, reproduce the square’s patterns of water drainage. The pattern thus translates the lines of flow of the rainwater and the curves, bifurcations and eddies it generates on meeting with obstacles on the surface (for example, the Torico Fountain) and below the ground (the two tanks). In their above-ground projection of the two cisterns, the luminous segments are so arranged as to follow the same orientation, and their density is reduced in order to express the static nature of water in a state of quiescence.

Given the limited dimensions of the square and in order to avoid any rivalry with the ground-level luminous pattern, the general lighting is subtle. A graze-lighting system has been affixed for the old lamp-posts that are joined to the facades and this uses the vertical faces of the buildings as a reflecting screen. In keeping with European Union criteria for minimising light contamination, the façades are bathed in tangential light in a descending direction. A false ceiling has been placed in the portico around the perimeter to conceal the now-renewed cables, which once hung visibly off the facades. The face of this ceiling is lit with diffuse lighting and the Torico Fountain is illuminated by concentrated clusters of lighting elements set on some of the facades.

Assessment

The main reason why the two medieval tanks of Teruel were concealed underground is so that they could accumulate the water running at street level. Moreover, at the time they were built, despite their strategic significance as service infrastructure, they had no symbolic or representative value that might have made them worthy of being made visible to the public. Nonetheless, the passing of time has diametrically changed this situation so that, if the tanks have lost the original use for which they were conceived, they have acquired great archaeological and educational value. This qualitative inversion of meaning ensured that their uncovering was extremely interesting for the citizens.The intervention has made the underground area accessible and has restored the archaeological remains so that they can be visited by the public. This is certainly a clear plus as far as culture is concerned, even though it is not such an unusual operation to offer an old construction that has lost its original function to a public that is expressly interested in visiting a once-closed precinct to see it. The most surprising aspect of this particular intervention does not reside underground but at the surface level of the public space, where the presence of the two tanks has become perceptible to everyone. Instead of a literal manifestation through their own architectural remains, their resurgence at ground-level is brought about by means of a poetic representation of the rainwater they once collected. The intervention superimposes an implicit restoration of an original function over the explicit restoration of an obsolete construction. Hence, by means of an allegorical element as functional as lighting, utility for once takes on a surprising degree of symbolism and representativeness.

David Bravo Bordas, architect

[Last update: 02/05/2018]