Previous state

Although Madeira’s main aquifers are to be found at the northern end of the island, most of the population lives on the southern coast in towns like Funchal and Câmara de Lobos, where the orography of the island is slightly less craggy and the conditions for agriculture are better. Since the sixteenth century, the need for potable water has led to the construction of a major network of irrigation channels, the “levadas” which, by means of costly tunnels and aqueducts, negotiate the constant obstacles placed in the way by the topography. Throughout the island’s history, the struggle to overcome and prevail over its jagged topographical features has strongly marked the relationship of the islanders with the territory.The artisan-based industry of Câmara de Lobos, which is primarily devoted to drying fish and salt extraction, has always been tied to the rugged coastal terrain of dense, black basaltic rock formed by the fast solidification of volcanic lava on contact with the sea. Cultivated plots, terraces, and retaining walls are constant elements in this beautiful coastal landscape. Today, the ancestral industries have made way for an economy that is mainly based on tourism, although the struggle with the wild background setting continues to be as relevant as ever.

Aim of the intervention

With the turn of the century, the need to adapt to the new economic reality led the town council to consider an ambitious transformation of the space occupied by some old salt pans and a lime kiln. This place of great beauty was derelict and had fallen into disuse. Without betraying its essence, the project was to revive traditional strategies, which are deep-rooted in the local culture, for domesticating the territory and adapting the space to a more public and up-to-date use.Description

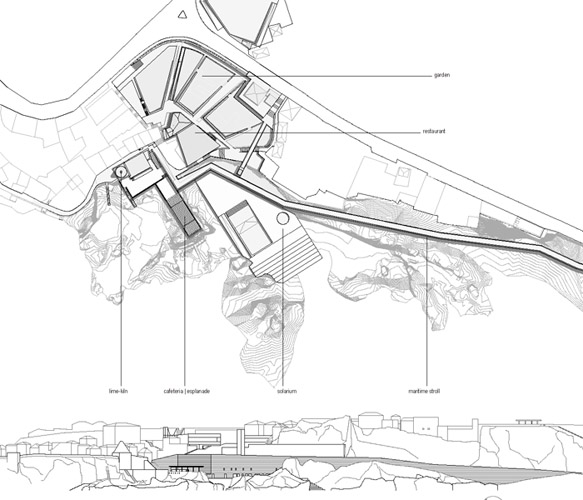

In a space of almost fifteen thousand square metres, the new Complexo das Salinas consists of a seaside walk, a square, gardens, public swimming pools and a cafeteria-restaurant. The whole project is set on four main levels with great differences in height and adapted to the complex topography of the pre-existing rocky base.On the lowest level, six metres above sea level, there is a large platform with two swimming pools and a solarium that descends in tiers to a small cove. The larger pool is rectangular and is set into one corner of the platform in such a way that on two of its four sides it looks as if its water merges with the sea and rocks in the background. Oriented true-south, the platform is protected on the northern side by a retaining wall of a height of some fifteen metres and finished with hewn basalt blocks. This wall, which forms the base of the upper seaside path, contains on the swimming-pool level, toilets, dressing rooms and the arrival point of a vertical nucleus of lifts and stairs that connect the platform with the upper part of the complex.

The pools can also be reached by way of some open-air steps coming down from a terrace with splendid views situated some ten metres above sea-level. The old, now-restored lime kiln is here along with a cafeteria, which is protected by a pergola. A further series of open-air steps leads up to a flat area at about twenty-four metres above sea-level where there is a wooden building that houses a restaurant. The seaside walk begins from this point, running some two hundred and fifty metres along the coast until it meets one of the main roads leading into the town. Above the restaurant are some gardens with a structure of poles and wiring in readiness for the growth of shade-giving vines. Still higher, at thirty-seven metres, there is a lookout-square that covers an underground three-storey car park. The square is the starting point of a footbridge that leads to the vertical trunk of the nucleus of lifts going down to the swimming pool.

Assessment

In a setting that is so craggy and steep, the achievement of a flat horizontal space is as valuable as the shelter of a roof would be in other circumstances. In keeping with the strategies traditionally used for agriculture, industry and local architecture, the intervention transforms the natural lie of the land in order to obtain a series of terraces that, because of their flatness, immediately become special identifying spaces. Now, however, these places are public spaces and the functional possibilities deriving from their horizontal condition are offered for the use and pleasure of everyone.Nevertheless, and in keeping with the geometric laws of ground clearance and levelling, the price of achieving this horizontal space is the potent appearance of new vertical surfaces that notably modify the natural landscape. In a lesson of architectural frankness, the Complexo das Salinas accepts this fact with the utmost naturalness. Like a “levada”, the basalt wall of the waterfront path unfolds its majestic verticality without disturbing the balance of the lovely landscape of dark rocks and escarpments into which it has been inserted.

David Bravo Bordas, architect

[Last update: 02/05/2018]