Previous state

After the fall of the communist regime and as a result of large-scale rural-urban migration, Tirana has recently undergone the most sudden and significant demographic growth in all its history, from 150,000 inhabitants in 1991 to the 600,000 people who figure in the census today. In the last decade of the twentieth century the city’s urban fabric was subjected to a chaotic, burgeoning overspill, which was spurred on by the economic expansion of an incipient capitalism that was both ferocious and unregulated. The new arrivals went to live in peripheral areas with informal streets, without water and light and sewerage and, in many cases, lacking even a name.

After the years of collectivisation, the limits of private property had been forgotten and public space, viewed with contempt as a failed idea associated with the previous regime, was indiscriminately filled with buildings. The open spaces separating the residential blocks of the socialist housing estates were invaded, while buildings exceeding the maximum permitted height or flouting any kind of regulation began to appear in the more central and consolidated neighbourhoods. Without any kind of juridical deterrent, both the banks of the Lana River and the centrally located Rinia Park were occupied by dwellings, kiosks, bars and small businesses, all of them illegal constructions of the shanty-town type. This urban-planning havoc spread through the city along with extremely high levels of environmental pollution resulting from an unchecked use of the private vehicle. Taking the car as a symbol of the new economic system, the population of Tirana euphorically embraced this new consumer good to such an extent that there is one car for every two inhabitants circulating in the city today.

Aim of the intervention

With the beginning of the new millennium and the limitations imposed by a very stringent municipal budget, the City Council of the Albanian capital began to attempt to remedy the situation. Among other endeavours, this response has included new planning for the river banks, demolition of buildings that did not comply with the regulations, recovery as green spaces of the interstitial areas separating the socialist housing blocks, renovation of urban infrastructure both above and below ground, and the restoration of many facades and flank walls, which have now been repainted in bright colours.

Along the same lines, the City Council presented in 2003 an initiative that, with the slogan “Duaj te Luaj!” (I like playing!), aimed to recuperate the public spaces that had been encroached upon or abandoned by way of introducing 100 sports and games areas for children and young people.

Description

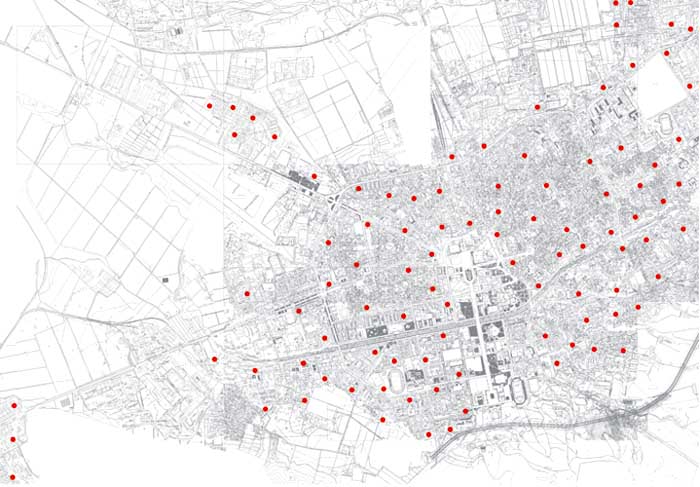

The first phase of the initiative consisted in the selection, in each neighbourhood, of the most suitable locations for introducing these sports and games areas. The criteria governing each selection were essentially the need for sports and games facilities at each point and the degree of urban deterioration it presented. These indicators were obtained by way of an exhibition in which the project was presented to the public. Besides being very well received by the citizens, it also resulted in the collection of a great number of proposals for different locations. A map of the city then showed the hundred points where the sports and games areas were to be introduced by 2009. At the time of writing, fifteen of these have been completed.

The majority of the sports and games areas are basketball courts since this is a very popular game among young people and it does not require large areas or overly specific equipment in order for people to play. They are surrounded by wire fences with metal stanchions and cross pieces painted in cheerful colours. They tend to be located at the foot of a flank wall or the blind outer walls of the socialist housing blocks, which are painted in the same bright colours in order to confer a unitary sense on the setting as a whole.

Each playing area, of some one hundred square metres, represents an approximate investment of four thousand euros. The City Council has covered a good part of the expenses but not all. In each neighbourhood, both businesspeople and residents have made small donations towards their construction while also being actively involved in improving their particular street or square.

Assessment

The simplicity of the project contrasts with the power and extent of its social and urban-planning impact. On a small scale, each intervention benefits a limited group of residents, providing a very specific solution to an urban problem of small dimensions. Each corner, whether it was run-down, invaded by cars, or occupied by illegal constructions, has been reconquered and reactivated as a public space for common use. Given the anarchic ferocity of the general milieu, the designation of this public space is accomplished without any ambiguity: the metal fences with their bright colours delimit and highlight their setting with unequivocal assertiveness. However, on the large scale, and as a network of branches of a single endeavour, its functional and chromatic constancy links up Tirana’s disorderly, fragmentary landscape so that the sum of the installations can be read as a unitary whole. And as a whole, the “Duaj te Luaj!” initiative is a large-scale, decentralised metropolitan facility that represents a small but decisive step towards the recovery of Tirana’s public space.

David Bravo Bordas, architect

[Last update: 08/06/2021]