Previous state

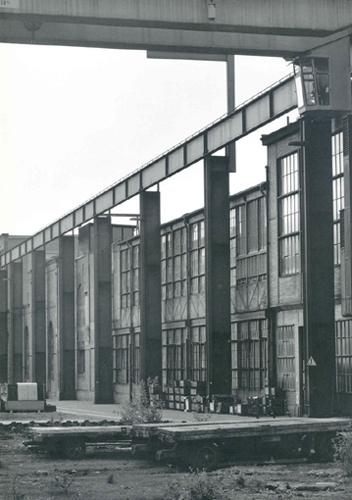

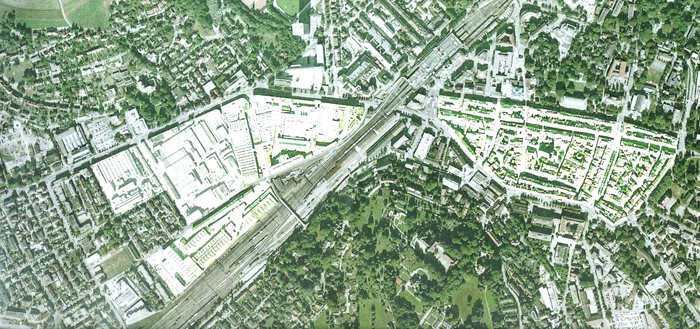

The old Sulzer-Areal industrial sector is right by the historic centre of Winterthur and its central station. Since 1834, when it was built as a foundry by the Sulzer brothers, this factory complex has spread out as far as the Zurich road and the railway line, forming an exceptionally dense urban fabric which occupies a surface area of over sixteen hectares. Even today its enormous industrial buildings and iron and steel production installations, with imposing bridge cranes on rails and gigantic diesel engines, remain intact and are an emblematic witness to the golden age of Swiss mechanical engineering.Since the 1980s, just after the expulsion of heavy industry from the city centre, different solutions were proposed for its post-industrial future. In 1992, after the total demolition option had been discarded, the Sulzer Immobilien AG group, which owned Sulzer-Areal, convened an international ideas competition which aroused great interest all over Europe. The winning project, called 'Megalou' and signed by Jean Nouvel and Emanuel Cattani, proposed a gigantic, ambitious restructuring of the sector. At the same time the abandoned estate had been taken over by small new technology firms until, in the mid-1990s, half the surface area was reoccupied, though now by clean industry. That spontaneous occupation coincided with a severe recession in the property sector which left the ‘Megalou' project without investors or tenants.

Aim of the intervention

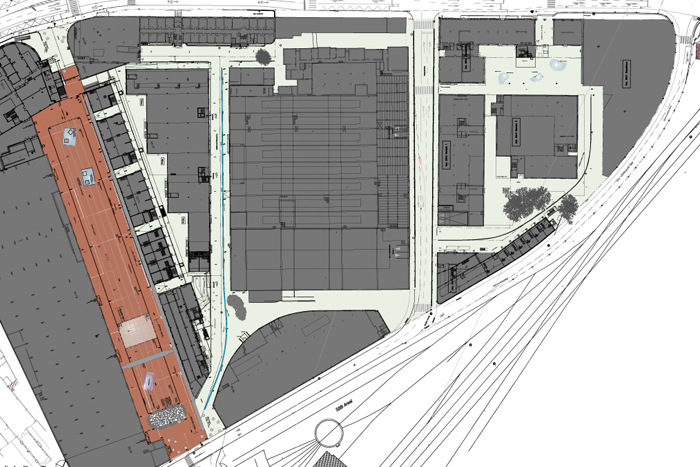

That brought about a rethinking of the strategy for the property which, in 2001, rejected the operation owing to the size of the investments required. Instead of intervening on the existing buildings, it was decided to make a superficial preparation of the interstitial spaces, turning them into public spaces that would act as catalysts for the gradual consolidation of the complex. The plan for the coexistence of residential, commercial and service uses found the adaptability and flexibility offered by those free spaces most suitable; they were conceived at the time with a functionalist objectivity which the new intervention had to respect and foster. Moreover, this new network of public spaces had the twofold function of connecting the Sulzer-Areal sector with the rest of the city, while preserving its autonomous, unitary nature.Description

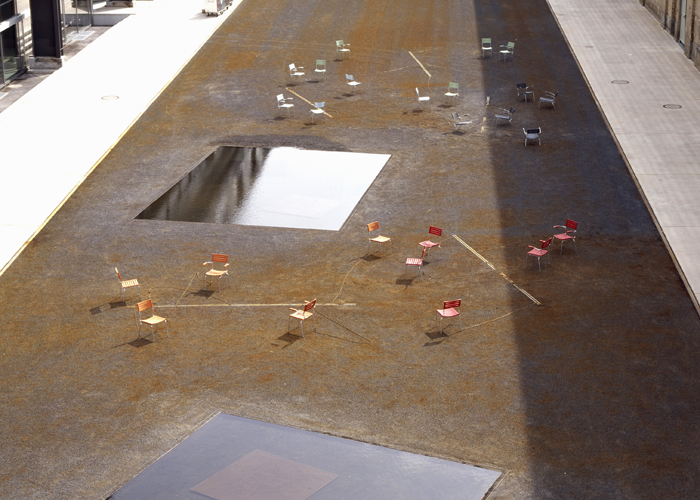

In the end the intervention focused on the far north-eastern end of the complex, the one closest to the historic centre of Winterthur and the station. Work was done on three free interstitial spaces that are clearly bounded by the presence of the industrial buildings around them. The most important is Katharina Sulzer Platz, a rectangular precinct two hundred metres long and thirty wide, which crosses the complex and connects the main road with the street that runs alongside the railway lines. The surface area is resolved with a hard perimeter strip that skirts a soft central zone. The perimeter strip is formed by a stretch of coloured concrete with small iron balls embedded in it. The soft central zone is covered with a conventional Netstal marl gravel mixed with pressed sand and steel balls and rings. At the northern end of the central strip there are three square pools with water that reflect the facades of the buildings. A number of chairs are scattered on the gravel. They are in five different colours and can be stacked. Among the chairs is an occasional elongated untreated steel sheet which recalls the rails of the cranes that crossed the space. Indeed, on the south side of Katharina Sulzer Platz the original rails are still conserved and along them a large crane, which has been restored, can move as well as a new platform that can serve as the setting for various events. Alongside that mobile platform there is another one, perforated at random by a series of round beds in which trees grow, forming a sculptural group.Another action point is the Pionierpark, a courtyard surrounded by the oldest constructions of the complex, built on an old coal mine. The paving, resolved with a layer of asphalt with rusty steel dust, forms small concavities which, when it rains, fill up with water to form pools. A narrow red steel drainage channel crosses the courtyard, marking the route between Pionierstrasse and the entrance to the old coal mine. Lastly, between Pionierpark and Katharina Sulzer Platz, in Turbinenstrasse, a galvanised metal drainage channel has been embedded in the paving to mark the route to the square.

Assessment

Although it was promoted by private initiative, this intervention uses public space intelligently as an instrument for enlivening a private precinct excluded from the city. With a subtle, poetic work on the ground, which is the supreme dimension of public space, the architectural heritage of the sector is revalued and connected to the city while keeping its identity.David Bravo Bordas, architect

[Last update: 02/05/2018]