Previous state

Despite its central location next to the Eduskuntatalo [Finnish Parliament] and Helsinki Central Station, until quite recently Kamppi was a fairly unconsolidated district. Its name comes from the Swedish word 'Kampen' [battle] because in the 19th century, under the Russian occupation of Finland, it was a military zone with barracks and training camps. For a few years after the occupation, the depopulated zone housed the Jewish Narinkka market, which was closed in 1929. On the occasion of the Olympic Games in 1952, the landmark Tennispalatsi was built and shortly afterwards became the most important cultural and recreational centre and in the city and, in the 1980s, with the construction of the Helsinki underground railway, one of the stops was opened there next to the Central Railway Station.Despite those contributions, in 2002 the Kamppi centre was still a large unstructured esplanade, chaotically invaded by dozens of buses that served the station located in one of the old military barracks. Whilst this building was too small to cope with the flow of passengers, the esplanade was an enormous rectangular area 450 metres long by 120 wide where buses and pedestrians lived dangerously side by side.

Aim of the intervention

In 1999 Helsinki City Council decided to bring some order to the zone, recover it exclusively for pedestrians and optimise the flows generated by the bus station. That launched one of the most ambitious and complex works in the history of Finland. With an investment of 150 million euros, a large underground nodal complex was built to house, on a surface area of 54,000 square metres, a new bus and underground station. On street level the esplanade was partially occupied by new buildings, generating a succession of public spaces with more controlled proportions free from bus traffic.Description

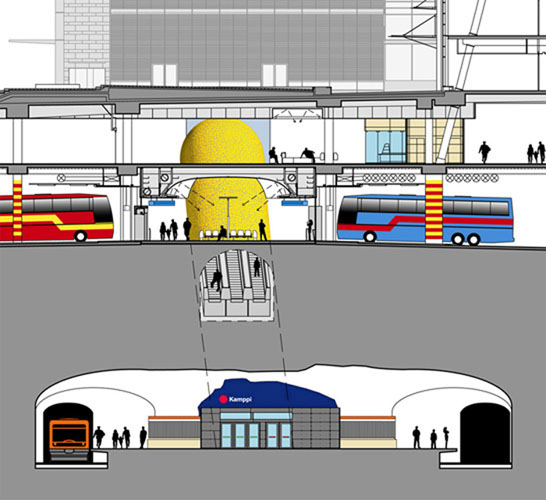

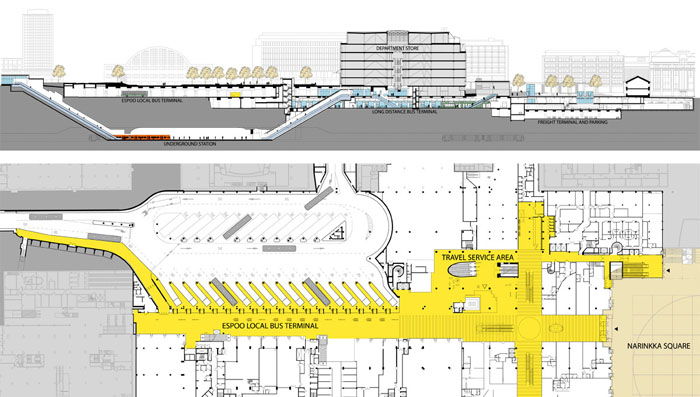

A new building six storeys high, which houses a shopping and recreational centre, divides the old esplanade to form two squares connected by Salomonkatu street. The square on the south-west side is framed by the landmark Tennispalatsi and on the other by a new triad of buildings designed for housing and offices. At the far end of the old esplanade is Narinkka square, a square precinct of about eighty metres along the sides and named in memory of the old Kamppi Jewish market. One of the faces of the square is the military barracks that had housed the old bus station and which now contains a new cultural centre. Both the new squares, like Salomonkatu and the three inter-crossing streets that lead into them, are public spaces reserved exclusively for pedestrians and provide the roof of a large underground bus terminal.All the buses enter the station by ramps at the ends of those streets, so that, as at an airport, in the whole intervention zone traffic never coincides on the same level with pedestrians, who enter the interior of the complex through the central building. On the first underground level is the local bus terminal, connecting the centre of Helsinki with its metropolitan area. One level below we find the long distance bus terminal, a public car park and a large logistic goods zone. All the passenger waiting and walking zones are enclosed in heated and air-conditioned spaces that receive natural light from large skylights on the ground of the squares. Moreover, all the spaces have large windows that provide direct visual contact with the bus access platforms. The whole complex is designed for the comfortable movement of the disabled or people carrying luggage. Moreover, the routes and entrances to the platforms are signposted with reliefs that can be read with the fingers or a stick. Lastly, thirty metres deep [fifteen metres below sea level], we find the Kamppi underground railway station, which has been refurbished to integrate it completely into the new complex.

Assessment

When it comes to describing this work in progress as a public space its condition as an enclosed, built space and the substantial presence of commercial and private surface areas cannot pass unnoticed. However, given the harshness of the Finnish climate we can easily understand the need to have covered, heated public spaces which in winter complement the open air part of the complex. Also, as well as making a valuable economic contribution to the financing of the intervention, the provision of private surface areas does not dilute the leading role of public transport in the whole operation. Moreover, the coexistence of public and private land, a characteristic of cities which normally occurs as juxtaposition, becomes superimposition here. That turnaround involves costly structural consequences but frees large amounts of space and substantially enriches the flows that converge on its different levels. Furthermore, the strategy is based on the conception of a civic structure that precedes the splitting up of the property. And so, in tune with the first urban utopias of modernity, the Kamppi complex synthesises a fragment of vertical city where public and private follow the pattern of a great structural symphony.David Bravo Bordas, architect

[Last update: 02/05/2018]