Previous state

Just before it flows into the River Main, the Nidda River enters the territory of Frankfurt through the north-eastern district of Bonames. Here, near the Rhine-Main regional park, the banks of the Nidda shape an extensive flood-prone zone, which is not suitable for building and which constitutes a transition area between the city and the surrounding territory. Nowadays, the river is channelled and several locks make it possible to regulate its flow when there is danger of flash flooding. Previously, however, the Nidda frequently overflowed its banks and the adjacent land could only be used for pasturing or crop growing. This was the situation until just after the end of the Second World War when the United States Army opened up an aerodrome, which was provisionally named after General Maurice Rose. Over time, a control tower and several auxiliary buildings were added to the land adjoining the runway and the installation became quite a major military heliport.In 1994, two years after the United States Army ceased to use the heliport, the buildings were occupied by Werkstatt Frankfurt e.V., an association working to find jobs for the long-term unemployed. The surrounding lands however were unused and neglected until, slowly and spontaneously, new users from the city discovered that the runway had considerable appeal. The four and a half hectares of asphalted surface, set in an ideal environment and, in particular, well away from traffic, offered the perfect setting for bicycle riding, roller skating and skate-boarding. Yet despite their popular success, the former military installations were partially contaminated and still made a notable impact on the landscape where, after years of neglect, nature was once again taking over. Their progressive physical deterioration and the ambiguity of their status did nothing to help their raison d’être in the medium and long term.

Aim of the intervention

In 2003, after acquiring the old aerodrome land, the Frankfurt City Council opted for a subtle intervention that, with minimal economic investment, could consolidate the natural character of the space. The literal restitution of the old riverside fields seemed, however, to be an anachronistic operation and, paradoxically, one that was not very sustainable. Demolishing and totally dismantling the installations would have meant a costly operation so a less unwieldy project was chosen with the aim of facilitating and attesting to the transition towards a more natural state while also making the most of popular support and, to some extent, conserving the historical connotations of the place.Description

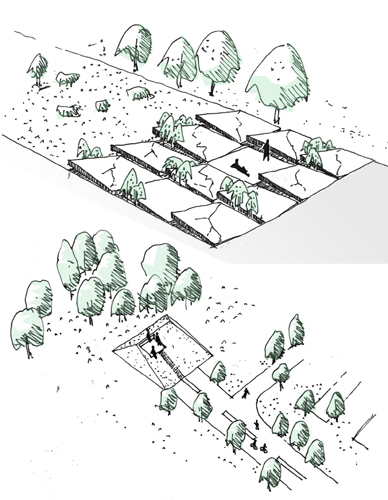

The intervention preserved intact one third of the runway, thus keeping one and a half hectares of hard, flat surface that can still be used as a recreation area and skating surface. The auxiliary pavilions have also been conserved and they still function as Werkstatt Frankfurt e.V. workshops. A café has been opened in the control tower and from this height it offers good views over the Nidda and surrounding fields.The dismantling of the three remaining hectares of runway was a sequential operation that intensified with distance from the buildings. Accordingly, the hard surface has been divided into zones and broken up into irregular pieces of a specific size in each zone. Instead of being removed, the pieces of concrete and asphalt have been left on the ground and, where once they formed an impermeable, continuous layer, they now present an uneven surface, full of buckling and cavities that plants and animals are progressively colonising. The different phases of natural growth vary with the weather and the degree of demolition in each section. The Senckenberg Research Institute is rigorously monitoring these changes and taking note of the animal and plant species that are arriving and the ways in which they are doing so.

Some of the concrete plaques have been piled up to form sculptural volumes of different heights. The contaminated asphalt of the eastern third of the runway has been completely removed and replaced by a stretch of concrete rubble. However, a narrow longitudinal strip has been conserved intact to facilitate walking and to give some perspective on the total length of the former aerodrome. In this zone, some fifty trees have been planted in a reticulated pattern, and other trees are scattered along the rest of the runway to grow through the cracks between the fragments of the old hard surface. Throughout the whole extent of the project, rubble-filled gabions delimit the different sectors and signal the routes. Some have been covered with wooden platforms, which convert them into comfortable seats.

Assessment

Demolition, which is frequently considered to be a merely preparatory phase, is almost never explicit in the finished work. In this case, however, the operation is undertaken with a particular awareness of this, leaving the process suspended in an intermediate phase so that it is given expression in the final result. Hence, an act of destruction becomes the first constructive phase in the intervention. The paradox arises from the fact that the starting-point situation – the presence of an alien element in a natural landscape – required a solution by way of subtraction and not addition. However, the high economic and energy costs involved in completely eliminating the military installations, and the large quantity of rubble that would have had to be dumped in a tip explain why, instead of removing everything, transformation was deemed to be a better option.The solution, then, was in partial deurbanisation of the site. Conserving some of the installations of the old aerodrome was justified by the new uses they have been given, making them more open to the public and more respectful of the environment. The breaking up of the asphalt crust accelerated nature’s takeover while also permitting observation of the process. On the small scale, the different textures adopted at ground level suggest uses and fun activities to visitors and, at the same time, have effectively eliminated the possibility of private vehicle traffic. On the large scale, and without wiping out the traces of its historic presence, the destruction of the runway generates a long transition – in both space and time – from urbanised ground to natural space. Halfway between the domesticated and the wild state, the site has not recovered the virginal purity of a riverside field but its success with the public, the legibility of its past and its poetic qualities have made it a much more significant and comprehensible place.

David Bravo Bordas, architect

[Last update: 02/05/2018]