Previous state

In the past the River Spree had played an important part in the social life of Berlin. As in other European capitals, in the 18th and 19th centuries the construction of bridges in the city centre became a widespread activity that produced examples laden with symbolism and character. In the early 20th century there were fifteen much-used public bathing areas on the banks of the Spree. Some were spaces defined in the river itself and others were nearby reservoirs called 'Badeschiffe' [‘bathing vessels'], which were fed with its waters.But before the First World War the growing pollution of those waters led to the closing of all the public bathing areas, and during the Second World War all the bridges except the Weidendammer and the Schilling were totally or partially destroyed by the bombing. The bridges built after the war are stark works of engineering which, avoiding any deviation from functional and constructive optimisation, confined themselves to providing an efficient response to the need for connections that arose during the process of reconstruction in Germany. Shortly afterwards the divided city turned its back on its river, which mostly overlapped with the frontier between east and west. Today, despite the investments made by the Berlin Senate since reunification, the banks and bridges of the Spree have not recovered the splendour of earlier centuries.

Aim of the intervention

In 2002, the StadtKunstProjekte, a public institution created for the purpose of promoting artistic interventions in public space, undertook a project which, with the name of con_con [constructed connections], brought together artists, architects and engineers to work on a series of interventions that aim at the recovery of the bridges and the banks of the Spree as spaces of life in the city. As one of those interventions, the Spreebrücke starts from the conception of the bridge as an element of connection, not only between two points but also between the city and the river.Description

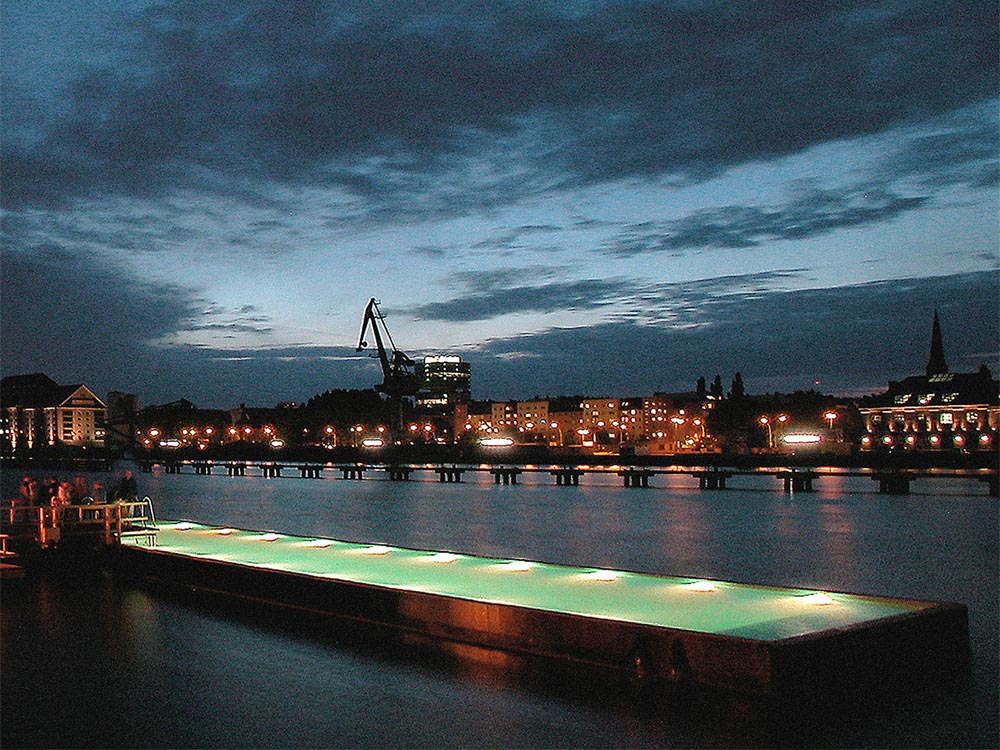

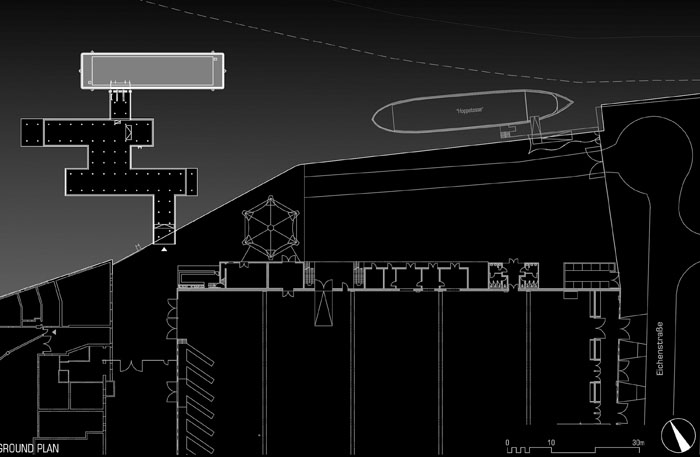

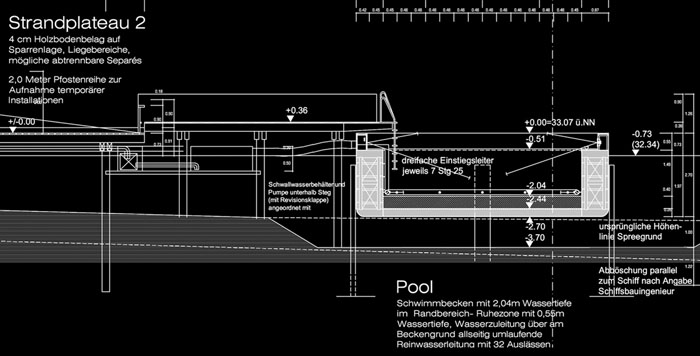

The Spreebrücke is a new floating bathing area that can be dismantled and moved to any point along the river. At present it is installed in the south-east of the city, just before the Oberbaumbrüke bridge. It consists of a swimming pool, an artificial beach, a bridge and a container. The floating container is the result of transforming a 'Schubleichter'–a kind of vessel which is very common on the Spree–into a swimming pool. After the roof has been removed, the hull of the vessel becomes a floating container which marks out a rectangular precinct of clean water on the surface of the river where people can swim in summer and skate in winter. Powerful blue and green lights set in the inside walls of the container illuminate the surface of the water. Two flexible metal structures secure the swimming pool to the bank. The pool floats or rests on the bed according to the flow of the Spree, so that its surface can be on the same level as or rise above the river.The artificial beach is formed by two rectangular, parallel platforms which are the same size and orientation as the pool and float beside it. They are built with a wooden dais resting on a flexible metal structure, easy to dismantle and transport. The bridge, which connects the beach with the pool, is an articulated piece which allows or bars access according to its position. A ‘Stueckgut-Container’, which is floating container for transporting goods and houses the pumps, filters and generators, as well as the bar, the toilets and the changing rooms.

Assessment

The Spreebrücke is a versatile facility, very popular with the public, where the Berliners and their river meet. But it is also the magical intersection between a specific cultural object and a universal archetype of public space. On the one hand the recycled 'Schubleichter' that forms the container for the swimming pool refers us to a local dimension of the project which takes up the tradition of the nautical industry of the Spree. On the other, it raises the inevitable analogy with the Roman public baths, hedonistic, civilising public spaces for social and cultural exchange. The result of that happy coincidence is a literal application of the term ‘Badeschiffe' which, now more than ever, deserves to be translated as ‘bathing vessel'.David Bravo Bordas, architect

[Last update: 02/05/2018]