Previous state

Like no other public space, Skanderbeg Square, Tirana’s nerve centre and symbolic site for the whole country, reflects Albania’s complex, convulsive history. “Skanderbeg” is the nickname given to Gjergj Kastrioti (George Castriot, 1405-1468), an Albanian nobleman who became a national hero after leading a long rebellion against the Ottoman Empire. Even the communist authorities, not known to be admirers of the nobility or Christianity, paid homage to him. In 1968, in order to commemorate the five hundredth anniversary of his death, an eleven-metre-high equestrian statue was erected on the south side of the square, replacing a monument to Stalin. Even today, for many Albanians the figure of Skanderbeg represents identity, integrity, and national independence in the face of the many aggressions their country has suffered over the centuries. However, Muslim Albanians see him as a Christian symbol reinforcing ties between Europe and the West.

Skanderbeg Square is the result of a neo-renaissance-style urban regeneration plan carried out in 1939 when Albania was occupied by fascist Italy. It was conceived as structuring a large urban axis consisting of Boulevard Zog I (formerly Stalin Boulevard) to the north, and Dëshmorët e Kombit (Martyrs of the Nation) Boulevard in the south, linking together the presidential palace and several embassies. A bleak extension of ill-defined perimeter and used simply for traffic and parking, the square gradually became an exceptional empty area in the densely populated and ill-planned city which has been growing around it for decades. The large number of emblematic buildings in the zone, an eclectic, messy jumble owing to the great diversity of regimes which have ruled the country, is an additional feature of the square’s exceptionality. On the northern side are the National History Museum (1981), the country’s biggest museum, and the Tirana International Hotel (1979) which was constructed on the former site of the old Orthodox cathedral. On the eastern side, where the old Ottoman bazaar used to be, are the Palace of Culture (1963), which houses the National Theatre of Opera and Ballet (1953), the National Library (1922), and also the eighteenth-century Et’hem Bey Mosque with its slender clock tower, which was reopened at the end of the communist era. Moreover, several government buildings are situated around the square, these including the City Council, the National Bank, and the ministries of the Economy, Agriculture, Infrastructure, and Energy.

Aim of the intervention

After 2004, an urban regeneration plan drawn up by a foreign studio advocated densifying the city centre by constructing several free-standing tall towers. The idea was to “modernise” the cityscape but some people saw it as an undeniable attempt to erase the complex traces of history. Between 2008 and 2011, the mayor, Edi Rama, commissioned an ambitious restoration of Skanderbeg Square which, without renouncing its symbolic values or the possibility of making it more welcoming, aimed to tidy it up and give it a more “European” character. The plan was to take space from cars without fear that the square would then be too huge to attract citizens. The desire to cede the space exclusively to pedestrians, public transport, and vegetation was not exempt of polemic. Indeed, it was so controversial that, after 2011, the mayor, Lulzim Basha, reversed the project. During his mandate, motorised vehicles once again took over the square, even destroying the green zone surrounding the equestrian statue of Skanderbeg.

However, in 2016, the new mayor Erion Veliaj, revived Edi Rama’s proposal with a new project which, wholly financed by state funding from Kuwait, had three main aims. First, it sought to create a large area exclusively for pedestrian use, eliminating the traffic and concealing parked vehicles in an underground car park. A second objective was to highlight the value of all the heritage buildings surrounding the square, and to endow them with some kind of unitary order. Finally, the presence of vegetation in the square was to be substantially increased in the hope of even setting off a new process of bringing nature back to the city centre. In 2015, just before work began, an ambitious process of public consultation was held. Besides validating the proposal, the idea was to enrich the project with citizen contributions and ideas from agents located closest to the square. Many of the demands thus collected were incorporated in the project.

Description

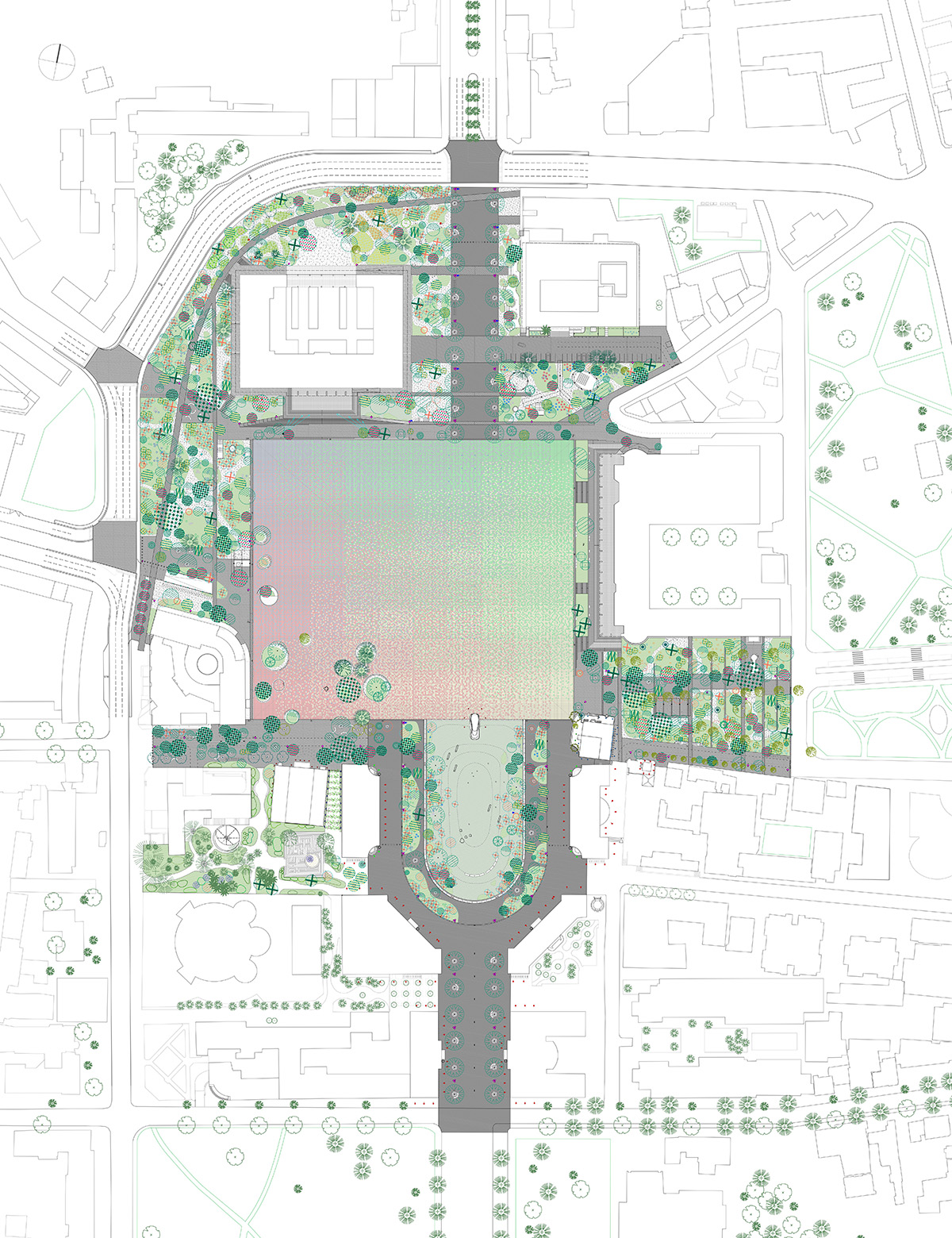

Finalised in 2017, the reforms eventually carried out have turned Skanderbeg Square into a public space of more than ten hectares exclusively for the pedestrian use. In the centre of the square there is a clear esplanade of almost 40,000 square metres. Rather than being flat, the esplanade is shaped like a four-sided Roman pyramid with a slope of 2.5% and a height of two metres at its tip. A fountain at the top lets water trickle down the sides, thus bringing out the colours of the mosaic paving which is made from stones from all over Albania.

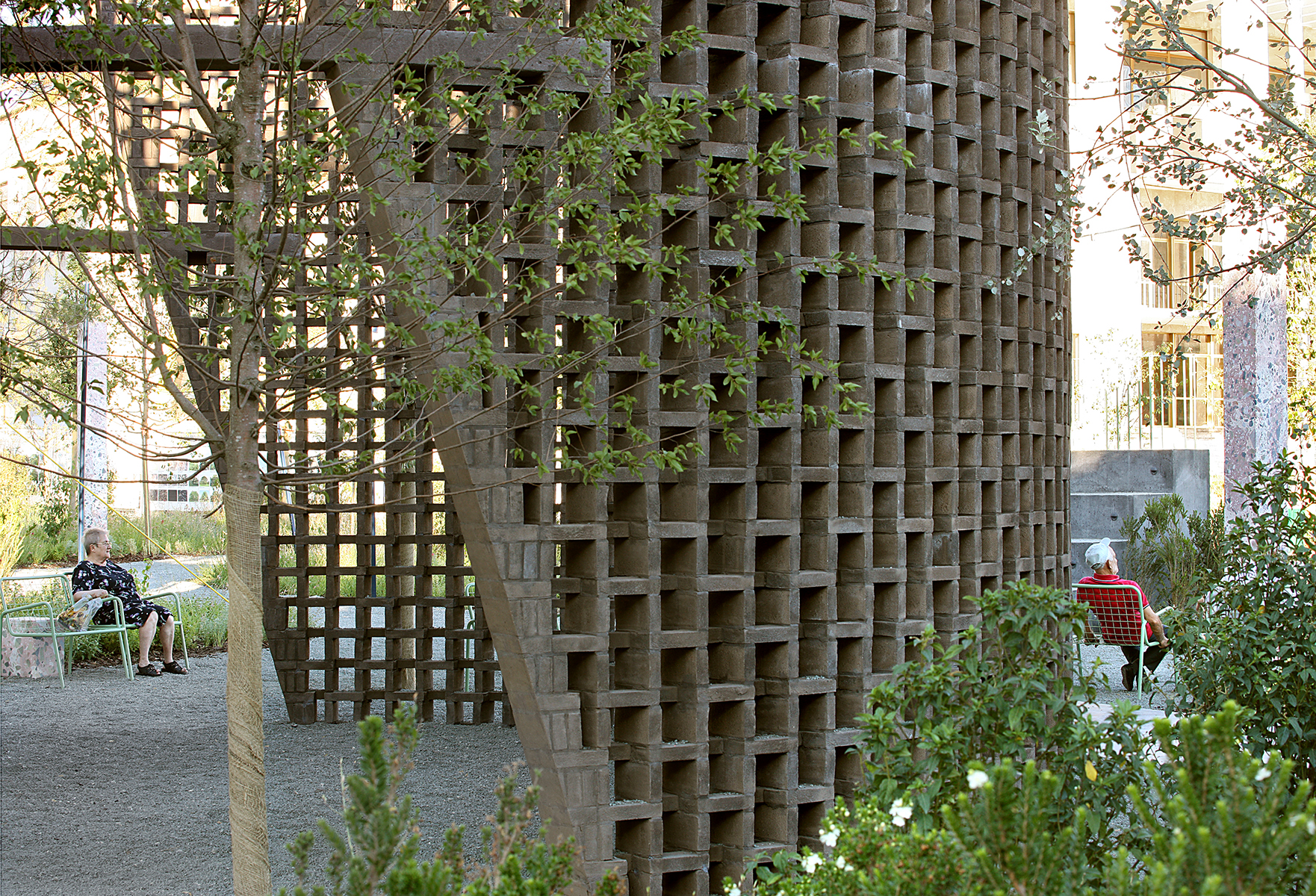

The absence of a continuous façade to delimit the circumference of the esplanade has now been compensated for with the introduction of a green strip circling the square in the form of twelve gardens with leafy trees. The nature and uses of these gardens were determined in a series of workshops held with users and people responsible for the adjacent buildings. As a result, the ground floors of the buildings are being used once again and now boast of semi-public exterior spaces in a gradual transition from interior space to public space that is open to everyone. Small additions like shade houses, latticework structures, and pieces of moveable street furniture to be used by people as they see fit, add distinctive touches to the different gardens, conferring intimacy and their own identity. One of the twelve gardens is that which, surrounding the equestrian statue of Skanderbeg, was once destroyed. Now it has been completely restored, extended to the north and renamed “Europe Park”.

Despite the specificity of each garden space, seen from a distance the front of vegetation consisting of the twelve gardens has succeeded in unifying the heterogeneous buildings around the square. In general, they soften the oppressive monumentality of some of the architecture and make the central esplanade look more hospitable. The green strip around the park also functions as a threshold since it presents a sort of shady antechamber separating the hubbub of the city from the sunny emptiness of the esplanade. All the vegetation is autochthonous in order to guarantee its adaptation and reduce maintenance needs. In fact, in future, this forest-like mass could be the starting point for more greening in the city centre.

Assessment

Albania has not yet developed a tradition for systematic attention to public space and, given its relative lack of resources, it is still far from achieving European standards in this regard. Moreover, the end of communism triggered a wave of enthusiasm for the private vehicle and a certain wariness of anything pertaining to the public sphere. Nevertheless, Tirana’s public space tends to be intensively, spontaneously, and informally used. True to their Mediterranean character, the people tend to spend time in the street and interacting with others. The restoration of Skanderbeg Square has made the most of this quality when taking space away from cars and inviting people to appropriate it as theirs. In fact the esplanade is now part of the biggest pedestrian zone in all the Balkans. The intervention has understood the country’s diversity and highlighted it. Now the space has a wide range of different uses, from morning prayers to evening concerts. It is even used as an occasional market for local farmers. In addition, work on the square, on a very considerable scale compared to what the country is accustomed to, has turned out to be a driver for economic recovery. For example, to supply the trees and all the paving stones from different regions around the country three tree nurseries were opened and abandoned quarries were reactivated. It is to be hoped that the renovation of Skanderbeg Square will extend in the form of other public spaces in the centre of Tirana, which had many underused empty areas which could benefit greatly from the same formula: more trees and fewer cars.

[Last update: 09/06/2023]