Previous state

Terras da Costa is a shantytown in Costa de Caparica on the outskirts of Lisbon. Mostly inhabited by a Romany community and immigrants from Cape Verde and, with 45% of its population under the age of eighteen, the shacks are constructed on land in an agricultural and ecological reserve. The settlement dates back to the 1970s when agricultural workers rented some of the first houses to be built there, but it was not until 2000 that it expanded when the vacant land was occupied and further construction began. Cut off from the urban area of Lisbon and with the stigma of illegality, the settlement’s greatest problem was the precarious nature of its houses which had no running water and, until recently, no electricity. Moreover, the community suffered from isolation and invisibility. However, although it was comprised by two ethnic groups, all the residents shared the same basic needs and were therefore able to forge a sense of the collective, which has only grown stronger over the years.Aim of the intervention

The impossibility of being able to intervene with the shacks gave rise to a five-year project with the basic objective of constructing a feeling of shared, common, public space. Hence, a process of discussions was opened up with the inhabitants about inventing a new neighbourhood and constructing it on the basis of what they had in common. The work was led by three entities: ateliermob, Colectivo Warehouse, and members of the community who talked about the needs of the residents and possibilities for acting on the outside space. All the meetings were focused on socio-spatial practices and the urgent needs of the population. By means of a process of intense participation, the programme concentrated on priorities, the most important of which was access to water which had to be situated at a point close to the houses. The first step was the construction of a community kitchen with a multipurpose structure so that it could be a gathering space for the neighbourhood and, at the same time, a place where residents could invite “outsiders” coming to the area and thereby contribute towards greater visibility for this Costa de Caparica community.Description

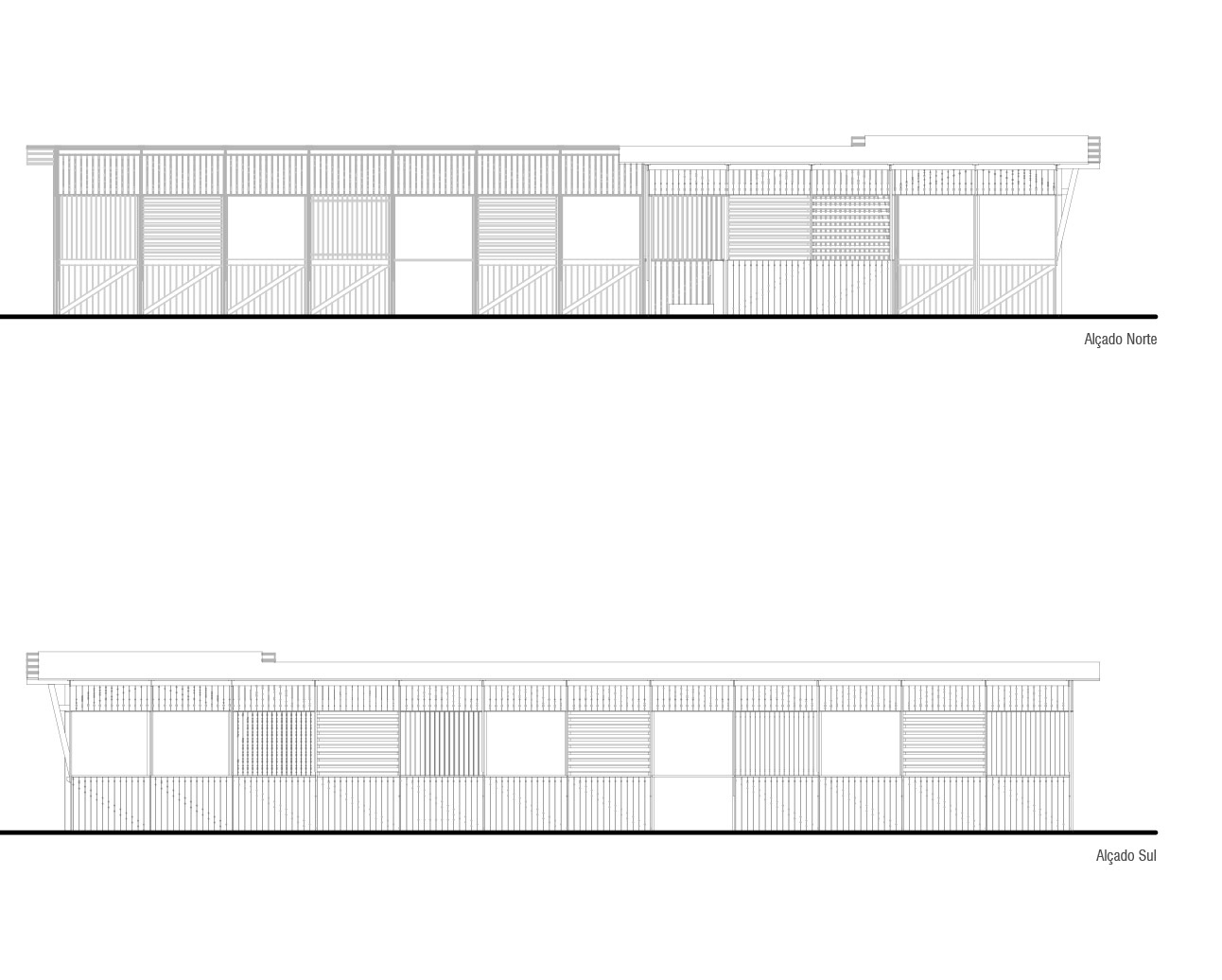

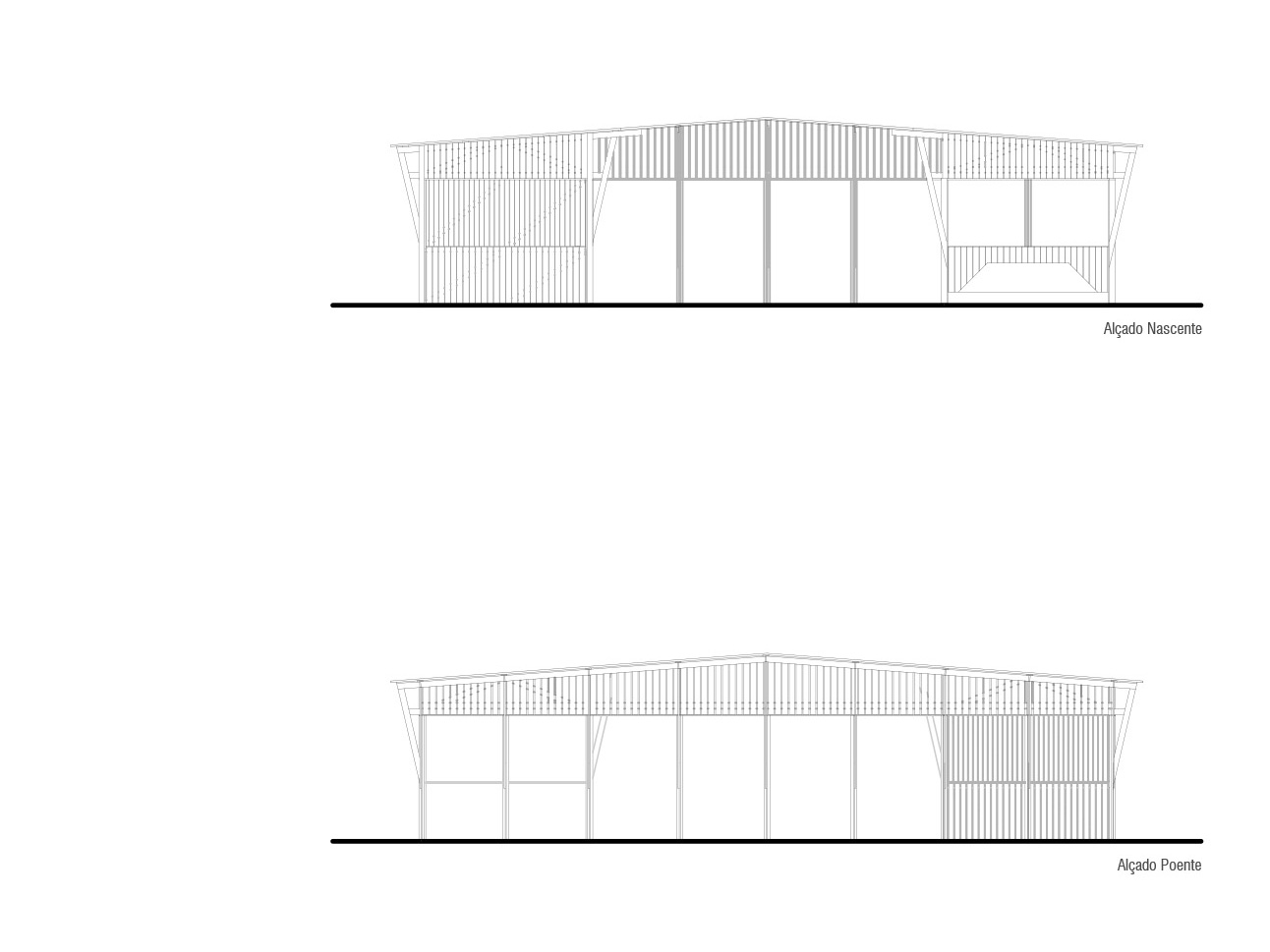

With a view to shaping a new future for the neighbourhood, the kitchen has been planned so that it can be converted into a true community space with a design that responds mainly to practical matters like a clean water supply and other sanitation functions. Until now, the nearest source of water for the residents has been a kilometre away. Habits of eating together were hampered by the lack of a suitable space but now an area fitted out as a dining room once again fosters this table-sharing tradition. The building is a simple L-shaped wooden construction closed off by shutter windows giving a permeable relationship with the outside. Besides having running water and equipment for cooking, the distribution of the kitchen allows an array of uses, for example with a laundry space and a courtyard clearly delimited by the new construction.

As a community meeting place for cooking and eating, the kitchen has also been envisaged as a space for all debates and a setting for collective discussions where pre-existing practices are borne in mind with the aim of conceiving new possibilities.

Assessment

Without a doubt, the kitchen has been the beginning of a process of rehabilitation which was not exempt of resistance, especially during the construction phase. However, this presented no obstacle to extending the initial limits of the work when the local authorities joined the project, precisely to provide a future solution for rehousing within the municipal limits of Costa de Caparica. At this point, rehousing became the main goal of all the work and the new focus has been favoured by the creation of a neighbourhood commission that has made it possible to hold the first meetings between the shantytown residents and municipal authorities. This fact has been essential for recognition of socio-spatial practices that are not wholly conditioned by the present living conditions. The right to the city claimed by the residents and the preservation of their cultural identity as a form of urban enrichment are the two starting points for their eventually coming to be part of the city.

Teresa Navas

[Last update: 11/12/2019]