Previous state

Since London was first founded, the Lea River Valley has been used as provisioning land for the city, covering its needs for energy, food, and water, as well as being a dumping ground for its waste. Thanks to the Lea River’s abundant flow of water it has, over time, worked mills, transported products, and received merchandise from everywhere. The Lea River Valley has been crucial for London’s economic development and is recognised as a true mainstay of the city. At present, its landscape is shaped by industry, technical processes, and infrastructure. Gasometers, power lines, sewage works, busy highways, railway lines, wharves, tanks, and tunnels have formed a topography consisting of a series of closed spaces aiming at resolving technical problems autonomously and by sector. In fact, as the result of 2,000 years of land use, this is an extraordinary valley but, at the same time, consisting of an inaccessible landscape, one that is difficult to navigate, monofunctional and, evidently, closed to the public. However, as the writer Iain Sinclair poetically observes, the Lea Valley has also been a place of invention, of plastic, dust, and India Pale Ale.

The main aim of the Lea River Park project was to transform this highly industrialised territory into a new public space for London, a revitalised space but also land recognised for its tradition of supplying the city of London. This required careful work, attentive to all the elements of the valley, both evident and hidden, in order to weave continuity between the heritage of the past and its future, with a feeling of celebration but also with an eye to what is to come.

Aim of the intervention

Sir Patrick Abercrombie, author of the Greater London Plan of 1944, envisioned that “… every piece of land welded into a great regional reservation” could become a large recreational park for Londoners. This was one of the ideas he put forth when he argued that the river valley should be converted into a twenty-six-mile long strip, a green wedge entering the city but also connecting the River Thames with the outlying spaces of London’s green belt. In 1967 the Lea Valley Regional Park Authority was established to manage a park for all kinds of leisure activities. However, downstream, some five kilometres of the Lower Lea reaches were cut off from the park and, as Tom Holbrook of 5th Studio pointed out, this kept people away from the zone. The idea of the project was to transform an urban area with an industrial past, giving it new centrality as one of London’s largest areas of new growth. In fact, its history of physical and social fragmentation was the crucial and most complicated factor that has to be confronted since the valley had always been both a meeting place and dividing line, an ancient boundary between London and lands lying to the east of the city. More recently, this fragmentation was reflected even in perceptions of the area expressed by different communities along the river banks. Creating the park, then, was an opportunity for reunifying the valley by means of new accessibility that would remove the river from its marginal status and locate it at the centre of new public space.

Description

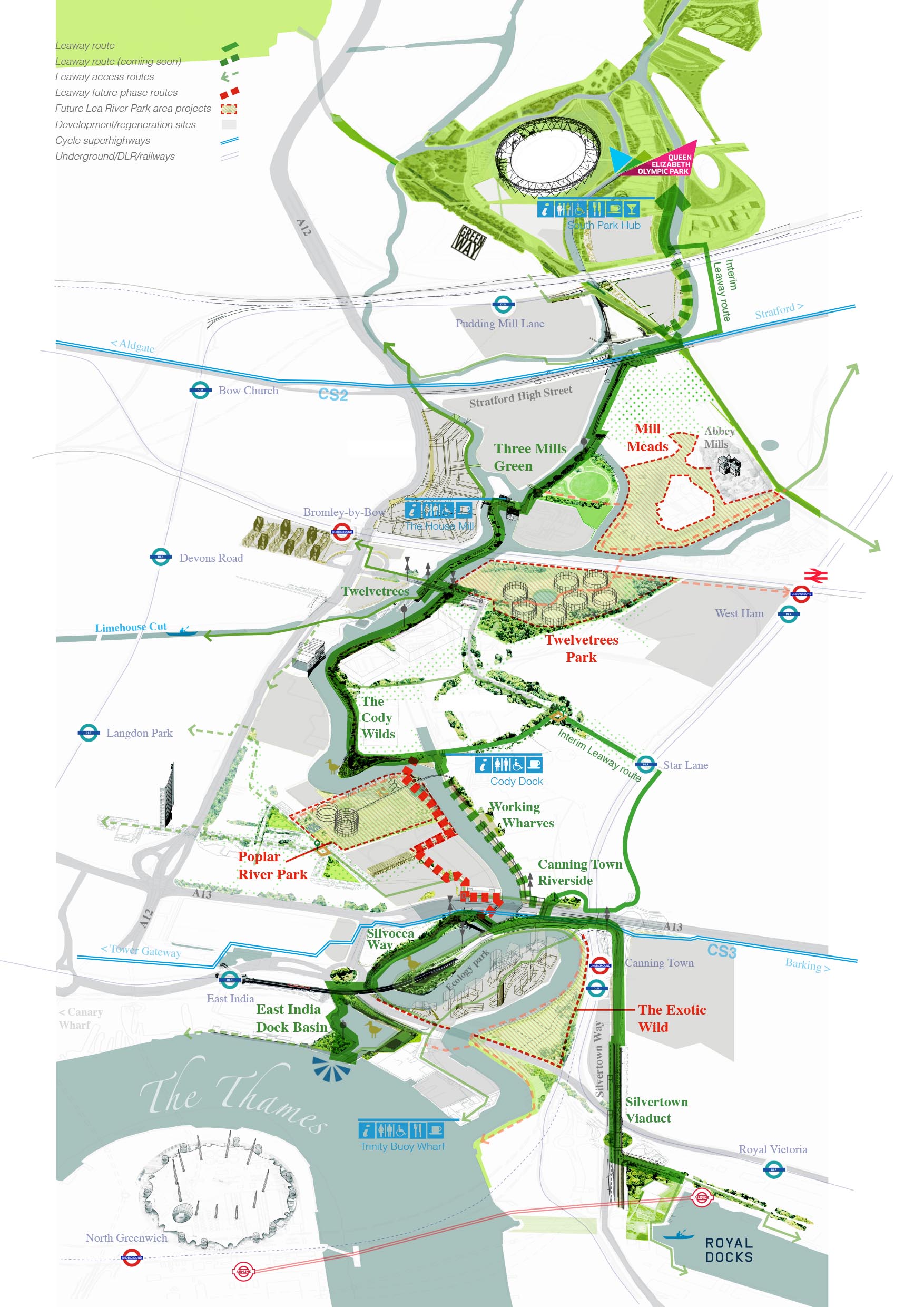

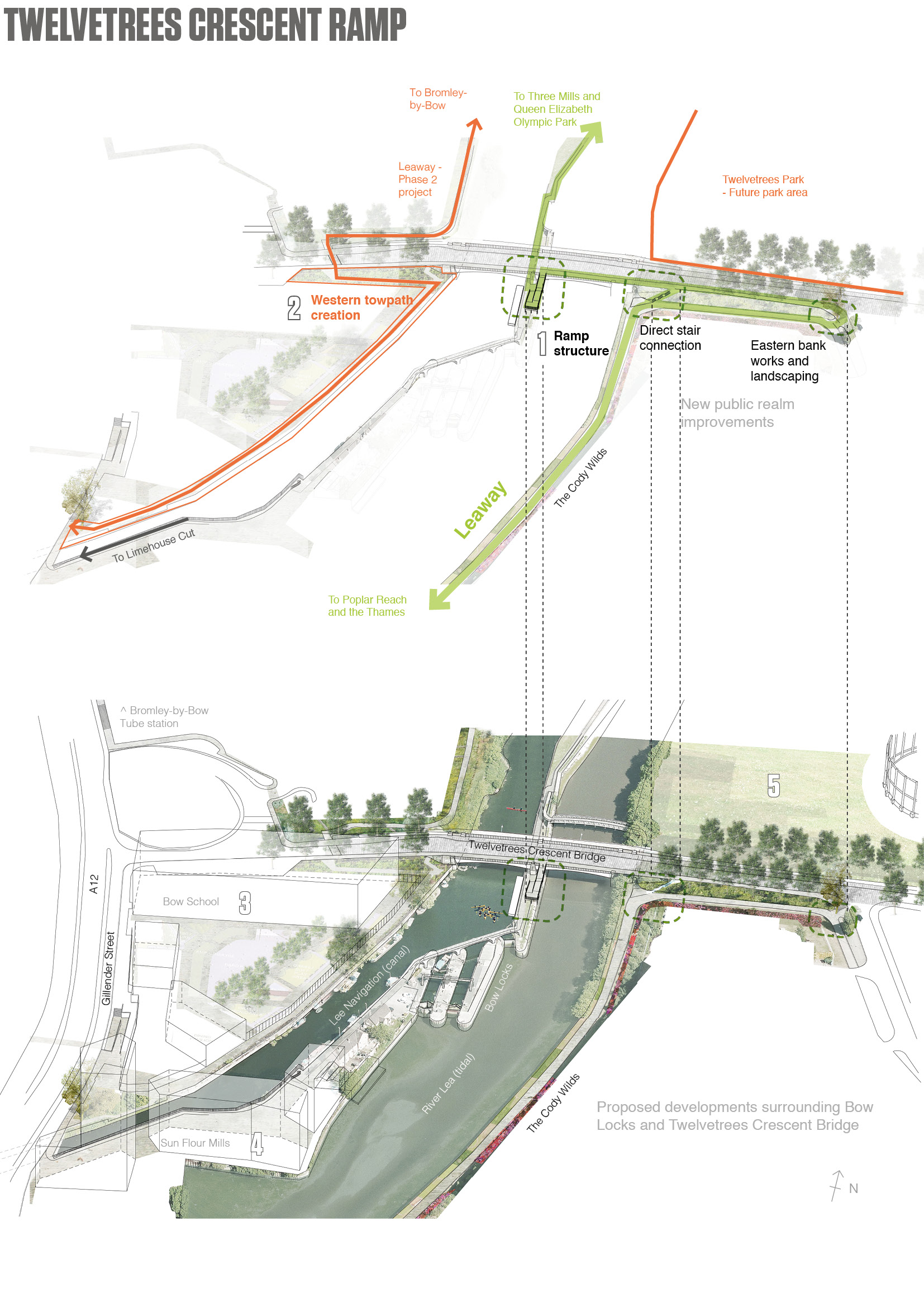

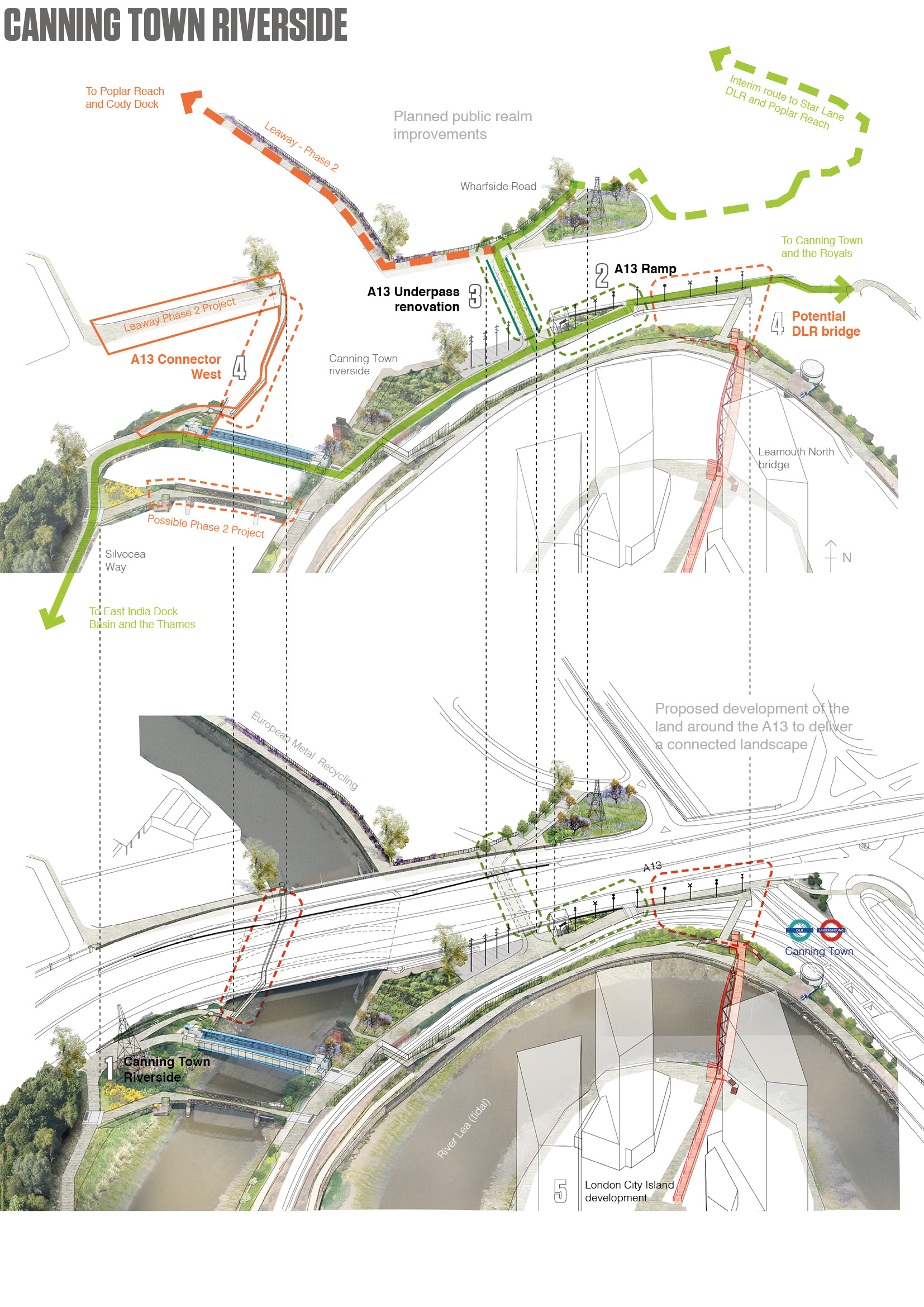

5th Studio worked for almost ten years to bring into being the final piece of Abercrombie’s vision. A document titled “Design Framework”, published in 2007, established the whole set of the project’s aims, ranging from a large number of participating members through to necessary strategies for land acquisition. This latter point was essential when it came to designing the route of the path that was to be called the Leaway. Planned for both walking and cycling, this is the structure that provides the link between the six central areas of the park: Three Mills Green, Mill Meads, Twelvetrees Park, Poplar River Park, the Exotic Wild, and East India Basin. Working with the studio Jonathan Cook Landscape Architects, the designers defined the landscape nature of some of the spaces along the route, in addition to those of Canning Town Riverside and Silvocea Way. With this set of interventions, the project has become a point of transition within a strategy prioritising connection between the new areas of the park which are, however, linked up with the work of numerous landowners. In order to achieve a coherent and well combined plan of all the parts of the project, two more basic documents were published, “The Prime”, which introduced the general concepts of the intervention, and “The Manual”, a design guide presenting the whole range of materials, urban furniture, and finishing touches which were to give continuity throughout the different spaces comprising Lea River Park. The new park’s relationship with the character of the place is patent, for example, in the paths along the riverbank which are now furnished with chunky U-shaped benches made with large pieces of timber from the Lea River wharves.

Assessment

When, after years of negotiation, Lea River Park was finally opened in spring 2017, the journalist Oliver Wainwright, writing for The Guardian, observed that the new Leaway, with its link-up points, bridges and ramps, and its solid presence as a riverside path—a clear model of constructive greening—conveys the feeling that it has always been there. The intervention has been possible thanks to funding from several public entities and, more recently, from the London Legacy Development Corporation and the boroughs of Newham and Tower Hamlets. It was necessary to adopt a gradual approach, one always in keeping with the availability of funds and the process of land acquisition, which was done by means of the initial investment for creating the Leaway. It is also true, however, that its authors had to work without clients at some points in the project, upon which they became its defenders, trying to keep it alive, working, and urging resilience and support among users who came to the river valley. At the end of the day, they are responsible for the real transformation. The result is a highly complex landscape, uneven and variable, notable for its fragility, and also one that has shown how surgical urban planning, which is tactical in the long term, has managed to create a new city route by stitching spaces together and reclassifying them in terms of their heritage value and industrial legacy: it is a kind of landscape homeopathy, as Tom Holbrook of 5th Studio puts it.

Teresa Navas

[Last update: 02/07/2024]