Previous state

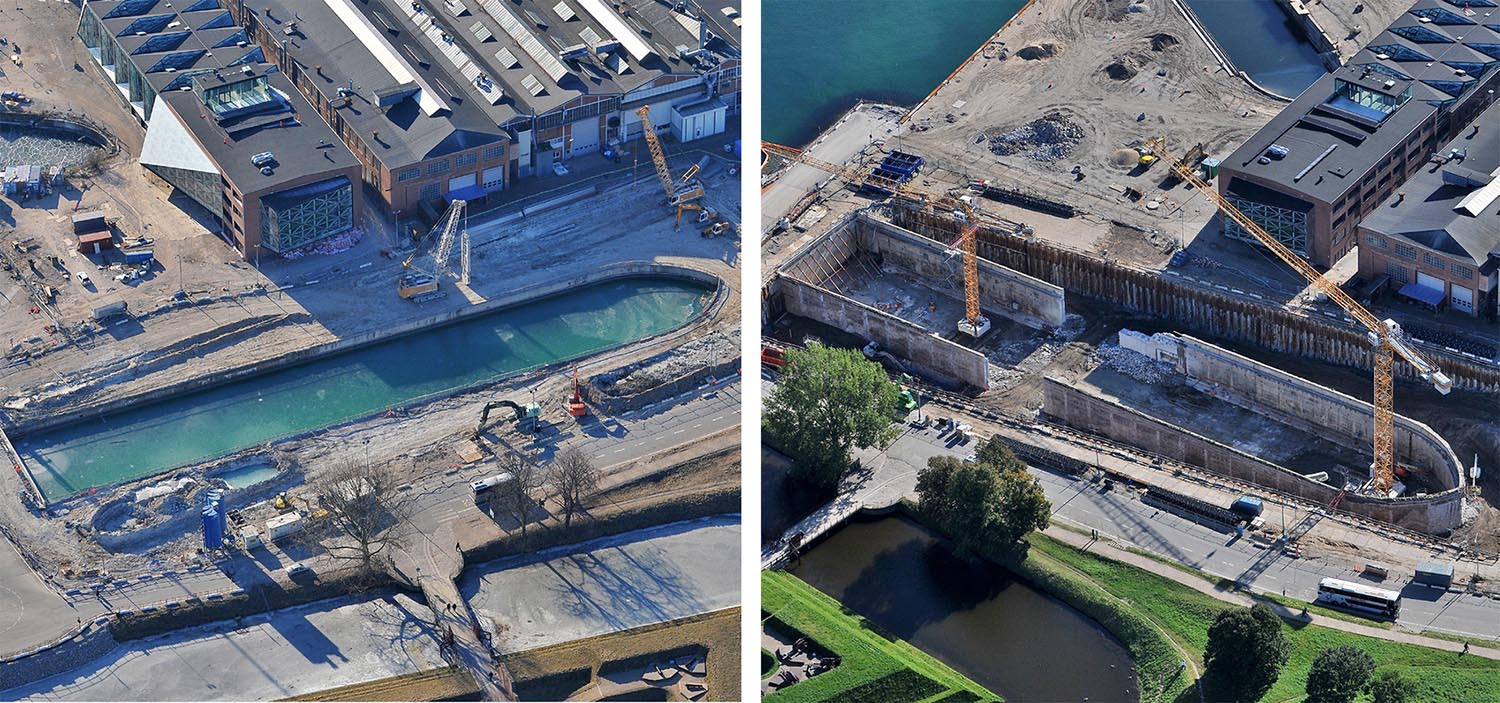

It is no accident that Shakespeare should have made Kronborg castle, one of northern Europe’s most renowned Renaissance buildings, the setting for his play Hamlet. For centuries, its position on the western shore of Øresund was highly strategic as a lucrative source of income for the Danish Crown, which taxed all ships sailing between the Baltic Sea and the Atlantic Ocean. In the mid-nineteenth century after the Strait Dues were abolished, the fortified complex was used as a shipyard, and thus came to play a major part in making the Danish shipping industry one of the foremost in the world. Testifying to these halcyon days of Denmark’s maritime history, the castle was opened up as the Danish National Maritime Museum in 1923. Nevertheless, among the effects of deindustrialisation in the last quarter of the twentieth century was the neglect and deterioration of the Kronborg shipyard, one of whose outstanding features was the former dry dock. Contradicting its name and symbolising the shipyard’s inoperativeness, this was left full of water, a measure taken in order to counteract lateral earth pressure on its retaining walls which were, by then, showing the ravages of time. However, this majestic hole in the ground, in the shape of a ship with a beam of twenty-five metres and length of a hundred and fifty metres, provided an opportunity for moving the Danish National Maritime Museum after 2000 when the Renaissance castle was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site and it was decided to empty the building in order to restore the interior to its original state.Aim of the intervention

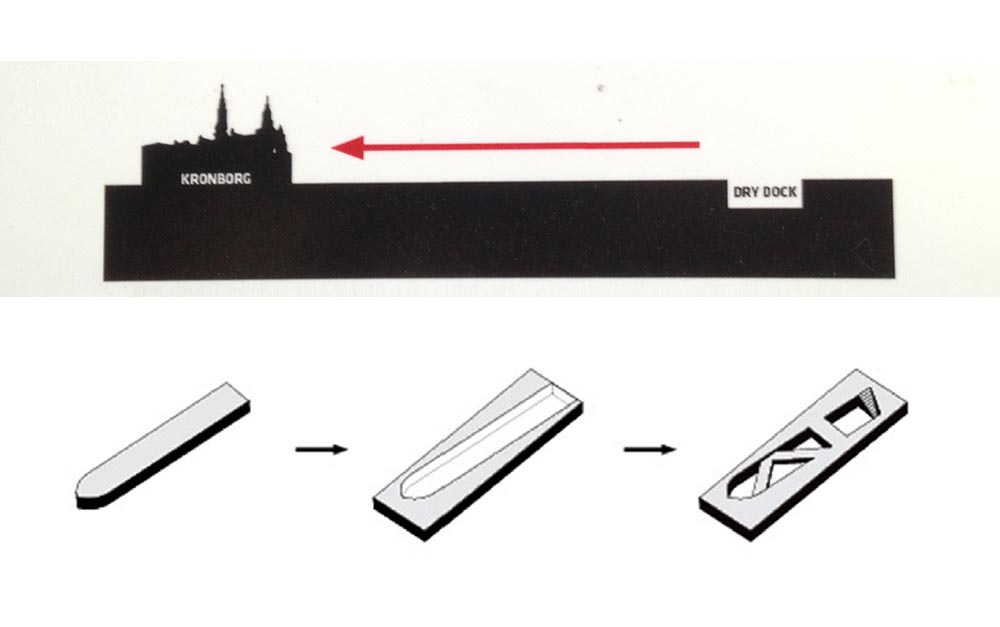

In 2004, four leading shipping companies each contributed €200,000 to finance an architecture competition for designing a museum to be located in the old dry dock. In order to avoid any obstacles that might block the view of the castle, the new building could not rise above ground level. This seemed to mean fitting it into the dry dock, which would have raised several problems. First, the plans for the new museum required a surface area that was double that offered by the pre-existing cavity. This would have entailed working at different levels with all the attendant difficulties of lighting and ventilating the lower levels. Second, it would have eliminated the dry dock’s most remarkable features: its distinctive ship-shaped concave space and its hydrodynamic properties. The winning project avoided these difficulties by turning the base of the dry dock’s cavity into the museum’s central courtyard. Eleven different foundations funded the work in order to bring the new museum into being.Description

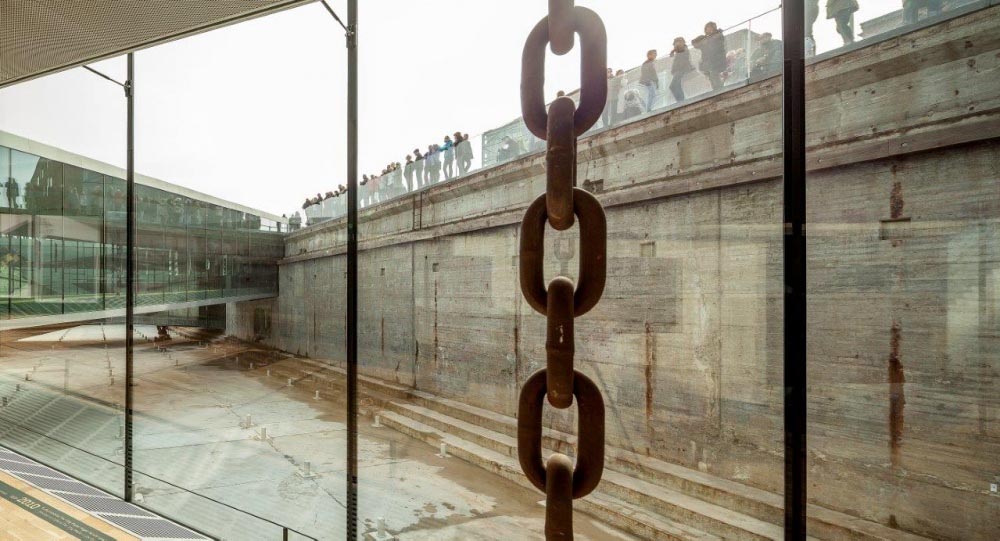

The new Danish National Maritime Museum occupies a rectangular space that has been excavated around the pre-existing dry dock which, once drained, revealed its former ship-shaped cavity. The old retaining walls, now free of lateral earth pressure, constitute the museum’s facades. The open space of the central courtyard is only interrupted by the presence of three suspended double-level bridges spanning the dry dock in zigzag form. The bridge at the eastern end – where the stern would be – is aligned with the entrance to the castle and its flat top enables pedestrians to cross from one side of the dry dock to the other. It contains the museum’s auditorium in which the floor is at a considerable angle in order to accommodate tiered seating. The other two bridges have gently sloping tops which function as wide ramps by means of which visitors can enter the museum. Two vertical stairways lead directly down to the courtyard, the ground of which flows as completely open space from stem to stern beneath the suspended bridges. The dry dock has thus become the museum’s outside space where people can move freely, as well as a venue for public events such as local festivities or concerts.Assessment

The single action of recycling obsolete infrastructure, namely Kronborg Castle’s old dry dock, has brought several benefits. Without adding to the built-up surface in a zone of great heritage value, it has provided space for the new maritime museum, thereby making it possible to free the Renaissance castle of its contents in order to restore it to its original state. Moreover, a disused, run-down post-industrial site has once again become a focus of activity with social and economic results extending beyond the bounds of Elsinore. Finally, this is a fine example of art trouvé in which a meaningful connection has been made between container and content. In brief, a museum devoted to the Danish seafaring tradition occupies a space left over from an old industry which testifies to this tradition. The museum in itself is therefore an exhibition object.David Bravo

Translation by Julie Wark

[Last update: 18/06/2018]