Previous state

Thursday 30 August 2007 was a tragic day in the Croatian history of fire-fighting. A fire broke out in the Natural Park of the Kornati Islands, which lie off the Dalmatian coast, and took the lives of twelve young firemen. Whipped up by a sudden blast of wind, the fire encircled them at the northern part of Kornat Island, the largest in the archipelago and the origin of its name. Six of the victims died immediately of smoke inhalation while the other six, who were badly burned, were evacuated by helicopter to Zagreb, where they too subsequently died.Although forest fires are by no means unusual in Croatia, whether they are the result of natural causes related with the Mediterranean climate or lit by pyromaniacs, this fire gave rise to controversy. Little light was shed on either the circumstances of its origin or the way to put it out. It seems that the fire could have been a case of arson and that the firemen were unnecessarily exposed to danger in this arid land where, apart from the value of the natural reserve, the fire did not threaten either people or property.

Like the other islands in the archipelago, Kornat is dry and rocky, almost a lunar landscape. Its original forests disappeared many years ago during the Venetian occupation when they were cut down on a massive scale to supply timber for the fleet. The subsequent islanders continued the process of environmental degradation by overgrazing sheep and intensive cultivation of olives. Erosion following upon deforestation, a process hastened by the soft chalky soil, sculpted a karstic relief, covered in rectilinear limestone pavements, scoring the land as the whims of the water dictated. In the nineteenth century, the island ended up totally depopulated and its land was divided up among the landowners of Murter-Kornati, the closest town. Beautiful dry stone walls built for protecting the olive groves and fencing in livestock still delimit these properties, carving up the island into an abstract grille and making of it a cadastre carved in stone.

Aim of the intervention

In 2010, three years after the Kornat tragedy, Šibenik-Knin County decided to build a memorial to the twelve firemen who lost their lives. It was hoped that the monument would have a cathartic effect on a traumatic memory which, given the considerable repercussion of the events in the media, family members and fellow firemen shared with the rest of Croatian society. At the same time, the intervention faced the challenge of minimising its impact on a highly valuable natural setting and landscape.With a view to meeting both requirements, a twofold strategy was adopted. First, Land Art language would be used in order to convey the meaning of the work in a dialectical relationship of respect for the landscape. Second, not only was the use of external materials and techniques excluded but, even as the very first sketches of the project were being made, the desire was expressed that the construction of the monument should be carried out by volunteers and without the involvement of any kind of mechanical help.

Description

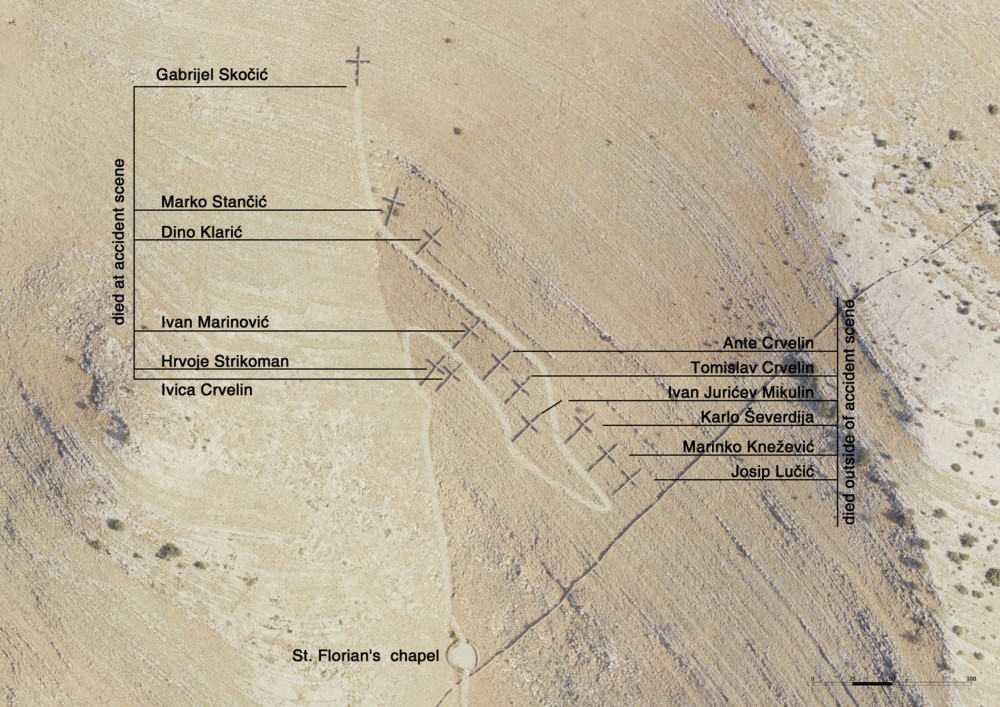

An open-air chapel opens into the memorial area. Dedicated to Saint Florian, patron saint of firemen in Central Europe, it consists of a simple dry stone wall that describes a circle around an altar designed to hold wreaths and candles. A vertical mast secured with guy-wires can support a canvas canopy at events attended by large numbers of people. A path zigzags away from here, climbing up the slopes and following the bases of twelve large crosses lying on the stony ground.The six crosses that are furthest from the chapel are in the exact locations from which the bodies of the firemen who died of smoke inhalation were recovered. The other six crosses are for the men who died in hospital. All the crosses are of identical dimensions but vary in their orientation to adopt positions in keeping with the parameters marked by the limestone pavements of the terrain and by its slopes, which do not always coincide. Each cross is formed by the intersection of two dry stone walls. While each wall has the same width of 60 cm, their height above ground level is about 1.2 metres and their lengths are different. The longer part is always 25 metres, running downhill, while the shorter arm is 15.45 metres, thus establishing a relationship of golden ratio with the other piece. As a result of the average slope of the terrain, about 25%, the longer section drops about ten metres from one end to the other, a gradient that means that the crosses are visible from the distance.

On each cross is written the name of one of the victims. Visitors are invited to write quotes, verses and dedicatory messages next to the inscription so that, beyond any artistic determinism, the crosses are open to being personalised over time by people’s contributions. However, this is not the only collective effort to which the memorial is indebted. The crosses were made by some three thousand volunteers from all over Croatia who, in this act of rendering homage that was not exempt of effort, difficulties and dangers, learned from local experts the ancient and almost forgotten art of constructing dry stone walls.

Assessment

This unusual intervention doubly challenges the limits of urban public space. On the one hand and, apart from the fact that about 90% of the Croatian population is registered as Catholic, it might be considered that, in the 21st century, ostentation of religious symbols is not in keeping with the laicism that is expected in the public domain. On the other hand, it is not easy to appreciate the urban dimension in an unpopulated setting such as this. In any case, the efficacy of the symbol of the cross in marking a precise point on the territory is not to be denied, and still less when it materialises by means of an element that is so much part of a landscape on which it rests, namely the dry stone wall. Moreover, the history of the place demonstrates that the island of Kornat is a much more anthropic landscape than might appear at first glance. The different exploitations to which it has been submitted have removed it from its natural pristine state.Anyway, both of these exceptions to limits can be explained by the desire to render homage to twelve people who died serving the commons. The megalithic simplicity of the memorial achieves the desired transcendence without constituting any kind of assault on the place itself. While it brings the different points into a coherent and unitary whole, it also respects the singularity of each one of them by means of the scattered positions of the crosses on the terrain. The stone work with rough-hewn rocks in different sizes reinforces the idea that no cross can ever be repeated. The work done with these stones, carefully taken from the soil that held them is what, in a moving commemorative offering, achieves such a remarkable, harmonious fusion between monument and landscape.

David Bravo Bordas, architect

[Last update: 02/05/2018]