Previous state

During the re-conquest of the Iberian Peninsula from the Muslims, Christians were frequently obliged to repopulate the reclaimed territories as a way of safeguarding them. In many zones in the north of the Peninsula, these extensive and scarcely inhabited territories were strategically settled by multi-polar networks of small rural settlements. Houses and isolated villages appeared in the surrounds of many walled cities, without their own jurisdiction and administratively dependent on the intramural authorities. This legally integrated but physically atomised territorial unit was called an “alfoz” (from the Arabic alhawz – district) in Spanish.The village of Rubena appeared in such circumstances, as part of the Alfoz de Burgos, some eleven kilometres to the north-east of the city. While it has the status of a municipality today, it has less than 200 inhabitants. Constructed with the Burgos road as its axis and its main street, the small settlement is in intimate relationship with its natural surroundings and the small stream that runs along its eastern flank. At the entrance to the village, near this uncrossable watercourse of leafy vegetation, are a fountain, a public washing place and a cattle crush, all of them dating back to the Middle Ages. Until recently they were in disuse, in disrepair and in danger of being swallowed up by the new and growing urban development nearby.

This threat was real and imminent because, in recent decades, the original dispersion of the region has notably increased. This is the result of the increasing mobility of private transport, along with territorial planning that has been ineffective in regulating the indiscriminate expansion of new industrial and residential zones. Besides interfering with the historical interpenetration between the small towns and their natural environment, this situation has hindered the consolidation of infrastructure while also constituting a dead weight hampering the economic and social progress of Burgos and its “alfoz”.

Aim of the intervention

In 2005, the Rubena town council responded to the assault of the new development that was jeopardising the natural environment of the stream and its medieval remains. The project for recovering this space and making it accessible was one of modest means but ambitious goals. In essence it sought a particular solution to the problem of how the small villages in the Alfoz de Burgos could maintain their relationship with their history and natural setting in present-day circumstances.Description

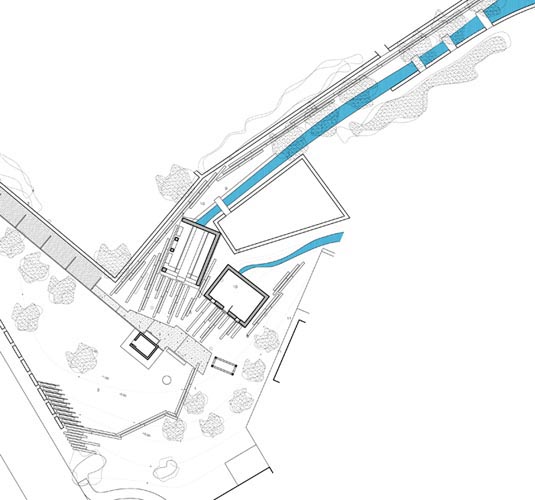

The natural space separating the old village centre from the new group of paired houses covers less than a thousand square metres. A bank with long steps made of concrete slabs leads down from the road to a small grassy level area next to the steam. New examples have been added to the trees surrounding this space and more concrete slabs have been distributed over the grass to define the area presided over by the fountain, the public washing area and the cattle crush.These three items have been restored. The fountain was formerly housed inside a bare-brickwork shed with a tiled roof, which has now been replaced with a less ostentatious construction, finished in wood-fibre panels and cement. The wooden structure of the cattle crush has also been set on new foundations, while the drainage around the edge of the laundry trough has been improved.

A new compacted gravel path leads from the flat grassy area in to the centre of the village, and a walk along the bank of the stream also starts here. The leafy stream-side vegetation has been slightly tidied, while more long concrete slabs have been set into the ground to mark the route and to facilitate accessibility and maintenance of the path. A series of gabions filled with white limestone separate the path from the streambed. They are both elements of protection and markers of the watercourse and, since they are not very high, they can be used as benches.

Assessment

Resides restoring the medieval remains, the intervention has recovered a neglected and impassable space, making it publicly accessible and identifying. It has done so with a minimum possible introduction of artificial elements in order to respect its natural character to the maximum extent possible. The subtle treatment at ground level where the concrete slabs and the limestone-filled gabions have been carefully positioned facilitates use of the space without dispelling this character.It is true that it would be optimistic to consider the result as definitive. Depending on what happens with the Alfoz de Burgos territorial planning, the natural space could, in the medium term, become a markedly urban park in the midst of built-up land. If this were the case, the intervention would have served to preserve the link between the old town centre and the green space. The direct contact would then give an explanation of the morphological genesis of Rubena and this, along with the presence of the restored elements as witnesses to its medieval past, would be a valuable contribution to the representation of its collective memory. For the moment, however, the intervention is postulated as an argument in defence of this memory and as an example to be followed in many other parts of the region.

David Bravo Bordas, architect

[Last update: 02/05/2018]