Previous state

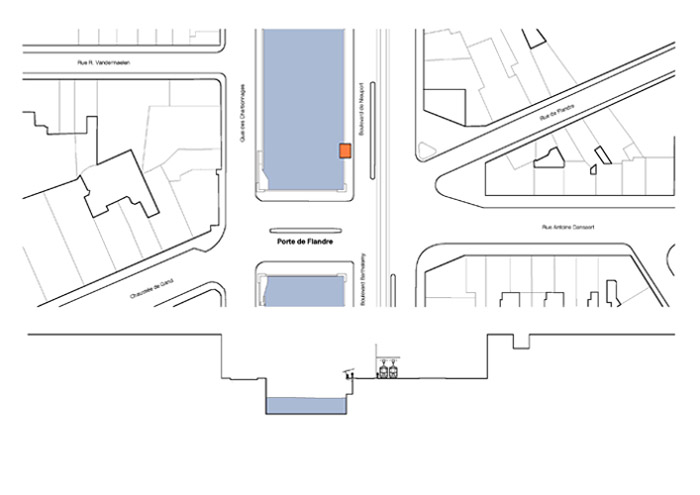

Built in the fourteenth century, the second wall of Brussels traced a five-sided polygonal perimeter around the present-day historic city centre which, accordingly, is popularly known as the “Pentagone”. Today the pentagonal outline is occupied by the “Petite Ceinture”, a ring-route of several lanes in each direction and considerable density of traffic. With excessively narrow pavements, this road cuts off the city centre from the River Senne, which flows at a tangent to the north-western edge of the “Pentagone”, constituting a barrier that is very difficult to cross for pedestrians while also thwarting a proper relationship between the city and the riverfront.Here, the main road from Ghent crosses the river and goes through the old wall at the Porte de Flandre Bridge, just after it crosses the Molenbeek-Saint Jean neighbourhood and before it becomes Antoine Dansaert Street, which comes to an end at the centre of the Grote Markt, the city’s biggest square. Next to the bridge, a rather remarkable construction that dates back to the beginning of the twentieth century, there is a stop of the line-81 tram route. Given the narrowness of the footpath, which makes it not possible to install a conventional shelter, the stop was unroofed until recently and was indicated with a simple vertical panel. People waiting for the tram, stranded between the river and the traffic, had no shelter on the many rainy days in Brussels.

Aim of the intervention

In 2004, the City Council and the Transport Ministry allocated a budget of just over two thousand euros for the installation of a specially-designed tram-stop shelter. However, beyond offering a solution to a merely functional problem, this small intervention was also more ambitious in its aims. Pending a project that definitively proposes a large-scale recovery of the riverfront, the shelter was to contribute towards the reconciliation between the “Pentagone” and the River Senne.Description

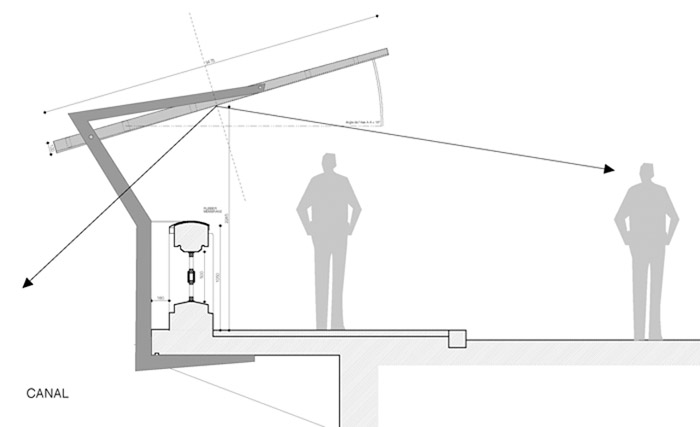

The new Porte de Flandre tram-stop shelter consists of two steel structural branches and a slanted roof of twelve square metres. The structural arms, two struts of 20 mm thick in the form of the letter sigma, are anchored on the lower side of the overhang formed by the wharf section. A horizontal brace consisting of a curved steel plate rests on a soft strip of neoprene placed on the wharf balustrade and supports the two middle angles of the arms so that the structure does not tip. The structure is therefore both solid and highly respectful of the extant wharf structure. It inflicts no physical change on the balustrade and can be easily dismantled without leaving any trace of its presence. The roof is a panel of 120 mm thick, fixed at four points to the steel arms. It slopes at an angle of 16º to the horizontal, which enables it to drain rainwater off into the Senne, while its lower face, covered in a mirror, reflects the surface of the river back into the centre of the “Petite Ceinture” roadway, and vice-versa.Assessment

The most strictly functional objects that populate urban space, whether they are street-furniture, signposting, or lighting elements, are industrialised products that optimise solutions of use and fabrication from a generic standpoint. In most cases and for obvious reasons, they are not conceived of as a response, from a more specific approach, to the particular features of the sites in which they are eventually located. Constituting an exception to this rule is the most relevant aspect of the Porte de Flandre tram shelter.The shelter’s particularity, which makes of it an almost crafted object, is its direct response to a precise problem – the narrowness of the pavement – which did not allow the use of a standard shelter. If it is true that its immediate functions of shelter and indication of a tram stop are fairly conventional, the form of its structure is so highly determined by the particular section of the Senne wharf that it could not be installed in any other place.

Yet this affinity with context goes beyond the scale of the industrial design to establish if not a definitive solution then certainly a valuable contribution towards reconciling the city with the river. As if a window had been opened in a blank wall, the roof mirror that reflects the waters of the river has re-established visual contact between both parties, awakening each one’s interest in the other, and calling for reunification. Surprisingly, the slope of the roof thus acquires a twofold sense. While its upper face drains the rainwater off to flow downriver, its lower face returns the river water reflected back up to the level of the city. In this illusory cycle of water, the people waiting for the tram are framed and dignified beneath a canopy that attracts gazes from all around. In some sense, the prosaic functions of a tram stop have acquired the transcendence of urban poetry: signposting has become an appeal and a simple shelter a noble canopy.

David Bravo Bordas, architect

[Last update: 02/05/2018]