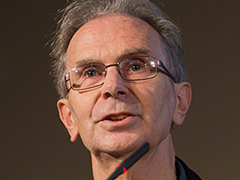

The director of the Centre for Mobilities Research at Lancaster University, John Urry, who is considered to be one of the most influential sociologists today, questions the short-term viability of the automobile as a means of urban transport.

On 24 November 2014, the British sociologist John Urry, who is considered to be one of the most influential in the field today, gave a lecture titled “Urban Planet: Mobility in Cities of the Future” at the Centre of Contemporary Culture of Barcelona (CCCB). Urry, director of the Centre for Mobilities Research at Lancaster University, used the occasion to review the historical evolution of the different forms of urban transport and also considered future prospects. In his view, the generalised motorisation of movement in the mid-twentieth century represented a conquest of individual freedom for the middle classes and the capitalist system in general. Moreover, the ubiquitous presence of the private vehicle reinforced two thriving industries: the automobile industry and the oil industry, together with the production of energy derivatives. This entailed a concomitant significant rise in road safety problems – in terms of both accidents and people being hit by cars – and an exponential increase in greenhouse gas emissions resulting from the use of fossil fuels, which is leading to ecological collapse and an energy crisis. Faced with this situation, some public administrations and private companies have begun to adopt solutions that not only turn out to be deficient since they do not resolve the problem as a whole but, worse, can even bring about adverse effects. Among the former type is the introduction of large-scale road infrastructure, which very soon becomes overloaded and obsolete, even during the planning phase before it is put into operation. Among the latter are conflicts deriving from the struggle for public space after traffic calming measures, pedestrian zones or bike lanes are introduced in some streets.

Finally, Urry holds that the mobility problem is global in scale and a matter that should be of concern to everyone. It should therefore be approached with joint leadership and the participation of all the agents concerned, including the administration, citizens and companies. He can only see four possible scenarios. First, would be the “highly technologised city” which would permit permanent real-time monitorisation of data pertaining to movement. Second, would be something like the “fortified city”, a battlefield of privatisation and competition for resources. A third variant would be the “digital city” in which physical movement would be radically circumscribed. The fourth and most desirable scenario would be the “habitable city”, which cuts down present-day scales of economic growth and urban development. In keeping with this last possibility, Urry upholds the need for a new kind of urban planning, which would favour a return of easily identifiable cities on a human scale instead of the megalopolis, which is spreading all over the globe. The new urban planning should favour the recovery of shared spaces and services which are now occupied and privatised by the automobile. New social practices should also be encouraged in terms of interpersonal relations, consumption and use of time. Some cities, Helsinki for example, are now considering these issues as medium-term (2025) projects by means of encouraging initiatives such as low-demand mobility. In any case, Urry warns that, sooner or later, cities will be obliged to take firm but generally agreed upon decisions on matters such as lowering individual income, cutting back consumption, reducing inequalities and, in brief, a major transformation of present-day social models.