After Barcelona, the exhibition Pasolini Rome will travel to Paris, Rome and Berlin on a cosmopolitan route in which steadfast urbanites can enjoy a true story of love for a city.

The exhibition Pasolini Rome fits neatly into a tradition that has come to be a feature of the Centre of Contemporary Culture of Barcelona – that of portraying internationally renowned authors through their own cities. Such mixture of the universal and the local, a good example of urbanite cosmopolitanism, is also expressed in the diversity of its curators - Alain Bergala from France, Jordi Balló from Figueres and Gianni Borgna from Rome – as well as in the scheduled path of the exhibition. After leaving Barcelona, it will open in the three other European cities in which the co-producing cultural institutions are based. Hence, it will be shown in January 2014 in the Cinémathèque Française in Paris, from March to June 2014 in the Palazzo delle Esposizioni in Rome and, finally, in the Martin-Gropius-Bau of Berlin, its venue until the beginning of 2015.

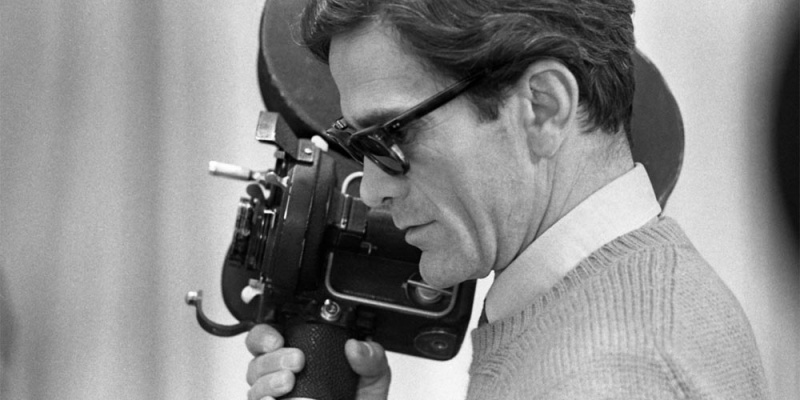

Apart from its production aspects, the exhibition is, in itself, a cosmopolitan manifesto which declares to veterans and novices alike the urbanite’s most deep conviction: the most universal city is the specific one. The true city is one that is trodden, is tangible and made up of real people, lived-in places, scruffy corners and edge dialects. It is a promiscuous, elusive city that shuns the completed form, is exclusive to no one, spills beyond any brand or postcard and doesn’t even fit within the idea it has of itself. The exhibition is a declaration of love to the city. Not a platonic, idealist or chauvinist love, but the carnal, ferocious and gross one with which Pasolini disrobed the imperial and Vatican city, laying it bare and making it revel in its most recondite ignominy. Moment by moment, neighbourhood by neighbourhood, the passion of the poet and of Rome is portrayed in a convoluted story full of wild flare-ups, disenchantment, distancing and re-encounters in which they were both transformed. Rome made Pasolini but Pasolini re-founded Rome.

Like so many other newcomers who fuel cities and make them what they are, the Pasolini who arrives at Rome’s Termini railway station in January 1950 does so as an impoverished, uprooted outsider. He had benn expelled from the village of Ramuscello in his native Friuli region, where homosexuality was still confused with pedophilia. He is immediately captivated, overwhelmed by the idea that “Rome is divine”. But transcendence can be very mundane in the eyes of a poet or in those of someone who has everything to do and with nothing to lose. Pasolini comes virgin but armed with a privileged gaze with which he sees the extraordinary in what others find ordinary. The exhibition shows how, in the neighbourhood where he settles in the surrounds of Rebibbia prison, he discovers the underground world of the borgate [shantytowns]. He wallows in their uninhibited argot, violent subculture and unhampered sexuality, sources of the inspiration which, following the publication of his first novel Ragazzi di vita (1955), opens the doors to recognition by Rome’s intellectual circles. The periphery, formerly held in contempt by official culture, is the key with which Pasolini conquers hardcore Rome.

However, once inside, he doesn’t opt for comfort. A headstrong free thinker, the eternal rover, he flees complacency and spurns certainties. He never stops prodding the city to discover itself, to recognize itself as it is. If his first work introduces whores and hustlers into Italian literature, in the trilogy with which he made his debut as a filmmaker – Accattone (1961), Mamma Roma (1962) and La ricotta (1962) ─ mixed neighbourhoods like Testaccio, Pigneto, Tuscolana or Parco degli Acquedotti find their place in Italian cinema. Pasolini never sees Rome as a mere backdrop, a set to sweeten his stories so they are easier to swallow. Streets, squares, motorways and vacant blocks are the raw material of his work. The exhibition shows, step by step, how Pasolini changes districts, working in the remote Campino, leaving Rebibbia to go to the crowded neighbourhood of Monteverde, in the Gianicolense area, with de Berrtoluci family as neighbors and, eventually, to the fascist landscape EUR residential district.

The whole of Rome is home to him and, even so, it gets sometimes too small. He gets into his car and, equipped with camera and microphone, escapes from Milan to Palermo, through Modena, Bologna, Florence and Naples and to check out the sexuality of his countrymen. In Uccellacci e uccellini (1965-1966), he absconds from the centre in the company of Totò and Ninetto Davoli ─ his human love ─ to explore the periphery and ascertain what is left of the Roman countryside. Beyond that, he confirms that, apart from indomitable Neapolitans, Italy’s old class structure is crumbling and the whole country is turning bourgeois. The real marginal culture on which his work is based is falling apart and being absorbed. Pasolini’s worst fears are confirmed: true fascism is the consumer society and this time it is finally taking over Italy.

Let down by Rome, he flies to other lovers. India and Africa, Paris and New York, keep him entertained for a while but he ends up coming home, resigned to keeping a distant proximity. At this point, a shock, he betrays the city – and perhaps himself – by outdoing the bourgeois fantasy of having a second home. He builds up two houses an hour away from Rome. One is in the country, to the north, between Orte and Viterbo, while the other is to the south in the coastal town of Sabaudia. The fact is that Rome has never been a faithful, unconditional mate for him. If, at first sight, the city succumbs to the seduction of the poet’s provocations, it also acts offended and is hypocritically scandalized, constantly accusing him and scolding him for his excesses. Even putting him through a calvary of thirty-three trials, Roman justice never managed to gag Pasolini. On the contrary, it was Rome that remained too mute after 2 November 1975 when the poet was murdered in still-murky circumstances, in a wasteland near the port of Ostia. He died in the periphery - one might say, making love - in the pat he had always preferred on his beloved’s body.

David Bravo │ Translation by Julie Wark