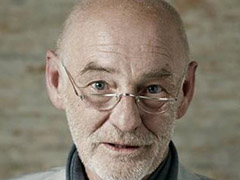

We mourn the death of Dietmar Steiner, director of the Architekturzentrum Wien from 1993 until 2016 and an old friend of the European Prize for Urban Public Space. This sensitive architect, aware of the complexity of the urban fact was the most veteran member of the international jury of the Prize.

The Austrian architect Dietmar Steiner, director of the Architekturzentrum Wien from 1993 until 2016, has died. An old friend of the European Prize for Urban Public Space, he worked tirelessly with the Centre of Contemporary Culture of Barcelona in order to make the award possible. He became involved with the Prize in 2002 when he agreed to join the international jury, although he was then wondering whether the democratic quality of squares and streets was still an incipient adventure or, at least, not very prominent. He remained faithful to his commitment until 2016 when he ceased to be director of the AzW, but not before paving the way to ensure that his successors would keep believing in the Prize. In all these years, he became the jury’s most seasoned member and, to a great extent, contributed to the recognition achieved by the Prize and the fact that it came to occupy its present place on the map of Europe. Always affable, he eloquently defended his views and enriched the jury’s debates with anecdotes of an inquiring, well-read, and well-travelled man.

Dietmar Steiner loved Barcelona. He loved it critically, without being totally beguiled and never overlooking its defects. During his visits to the CCCB, he never missed a chance to go off and wander the streets of the Raval neighbourhood. The time it took to have a cigarette or a beer was sufficient for him to come up with some sagacious observation. Sometimes he criticised the city for not sufficiently valuing its own reserves of richness, which is manifested, he said, in the spontaneity of an intense, diverse landscape. On other occasions, he accused it of excessive formality, of being too dressed up for visitors. In any case, he always expressed the view that, in Europe, Barcelona is a privileged observatory when it comes to recognising the strengths and weaknesses of urban space. True to the spirit of the Prize, he enjoyed pondering the European idea of the city. What distinguishes it? What remains of it? What does it lack?

He never tired of repeating that, if the European city has one distinguishing property it is the fact that it “is made for pedestrians”. Perhaps this is why he emphatically supported giving an award to the project of pedestrianising Exhibition Road in London (Special Mention in 2012), which understood the street as a “shared surface” where drivers have to slow down and be attentive to people who are cycling or walking. He was also very much in favour of presenting an award to the project of refurbishing the banks of the River Ljubljanica (Ljubljana, ex aequo Prize in the 2012 award) in which the riverside spaces were taken from cars and restored to pedestrians.

Aware that the “city of pedestrians” is only possible under certain morphological conditions, he upheld compactness in urban fabric and density in social fabric and, opposing the urban sprawl that thins out American suburbs, he wanted a Europe of compact cities. Opposing social and functional specialisation of large urban sectors, he advocated a Europe of mixed, diverse cities: big, small, or middle-sized cities, but always mixed and compact. This was his idea of the European city, one that was both urban and attentive to the rural landscape which, he said, modern architecture had not known how to respect. Maybe this was why he obsessively yearned for a renaissance in architecture. Against tabula rasa or blank page architecture, he wanted an architecture that was sensitive to the pre-existing bounty that so enriches Europe. And, as always, he had an anecdote to enliven his thesis. In his view, Blade Runner taught us that the city of the future is already constructed, and that we shall never again see utopias built from nothing but, rather, we can only have those resulting from negotiations with decisions our forebears made long before we appeared.

An admirer of the harmony of the classical European square, he argued that the main risk for public space is that it could change its form. Nevertheless, he showed that he was willing to accept that the “new architecture”—the coming architecture—should explore its own formal solutions. After all, he said, the quality of public space goes beyond materiality. It also depends on certain political conditions, like ownership, representativeness, freedom of access, and abuse of power. After discussing the matter with Manuel de Solà-Morales, president of the jury for the 2008 award—who died some years ago—he was willing to accept that a football stadium or a shopping mall could come to be understood as public space even if they charged an admittance fee or their monitoring was not subject to democratic control. Space is not public because its owner says it is but because the people who gather there consider that it is. This might be why he expressed such a liking for public and private buildings that present their roofs to the city as accessible or transit spaces, for example the Oslo Opera House (ex aequo winner of the 2010 award), which he defended despite his misgivings about big-name architects, among whom feature the authors of this project.

Dietmar Steiner had his doubts about the star system that gave such allure to the architecture of the 1990s. He was critical of the notion that architects are artists. “Once upon a time, the building was in the foreground and the architect in the background” but “at the end of the eighties, the positions were reversed”, he protested. This might be why he yearned for a new architecture. An architecture with a social conscience. A profession that would share out opportunities among young and outsider architects. Sensitive, bold architects who are aware of the complexity of the urban fact. Architects like you, our friend, Dietmar Steiner.