Previous state

Nørrebro is Copenhagen’s most restive district. On several occasions from the 1980s its streets have seen the biggest riots in Denmark’s recent history. The violence of the clashes between police and demonstrators, who were protesting over issues ranging from Denmark’s joining the European Union to the eviction of an occupied cultural centre, has remained engraved in the minds of Danish television viewers, thus contributing towards the stigmatisation of the neighbourhood.

Apart from the media flurry around these particular events, everyday life in Nørrebro is to a great extent determined by the challenges raised by the tremendous cultural diversity of its seventy thousand inhabitants who come from more than sixty different countries. Turks, Pakistanis, Bosnians, Somalis, or Albanians share an urban setting in which small private houses coexist with cooperative housing blocks, local bars with public schools, and main roads with quiet tucked-away corners.

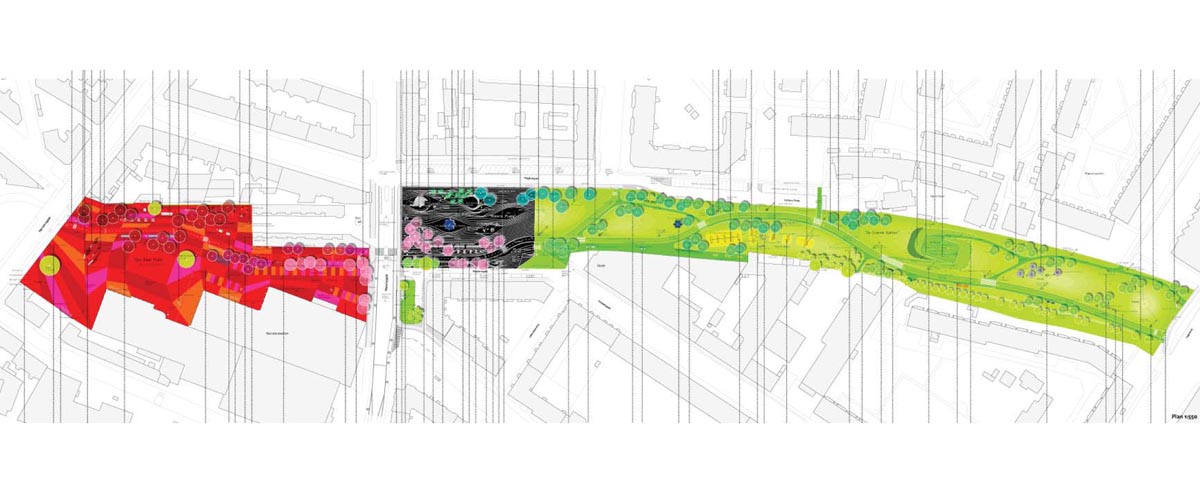

The latter situation was the case of a strip of land of some eight hundred metres in length which, unused for several decades, ran in a north-south direction, slashing through the urban fabric of the neighbourhood like a giant scar. Once the railway line that had previously taken this route was dismantled, this land remained as a forsaken, locked-away space populated only by undergrowth. The adjoining buildings faced away from it, hidden away behind trees and fences. Only dimly lit by a few street lights next to a path, it was a gloomy, dark place at night. Nevertheless, the land was bounded at either end by Nørrebrogade and Tagensvejdues streets, both of which are bustling shopping zones, full of shops and restaurants from all over the world.

Aim of the intervention

In 2008, the Copenhagen City Council joined forces with an association of real-estate businesses engaged in a non-profit-making project of transforming built-up areas and they managed to raise a sum of almost eight million euros to transform the space into a park that was to be named “Superkilen” (Big Wedge). The intervention aimed to take the neighbourhood’s cultural diversity not just as a starting point but also as a quality to cherish and celebrate, a factor that would inspire all the spaces of the park and bring the local residents together around ethnic, cultural and linguistic references with origins in many parts of the world.

In order to achieve this, it was necessary to understand the project as an open, collective creation based on exotic imaginaries contributed by the residents of Nørrebro as well as the joint multidisciplinary work of architects, landscapers and artists. In brief, the new park might inspire many other cities as an example of how to approach the cultural diversity of their neighbourhoods.

Description

The “Superkilen” has been planned as a world’s fair of elements of street furniture, leisure and sports facilities, art installations and plant species from all around the world. Many of these components were suggested by the residents themselves. Apart from connoting the space itself, the great majority of these elements perform the same functions for which they were originally conceived. Some have been imported from their countries of origin and, when this proved to be impossible, others have been produced as exact copies.

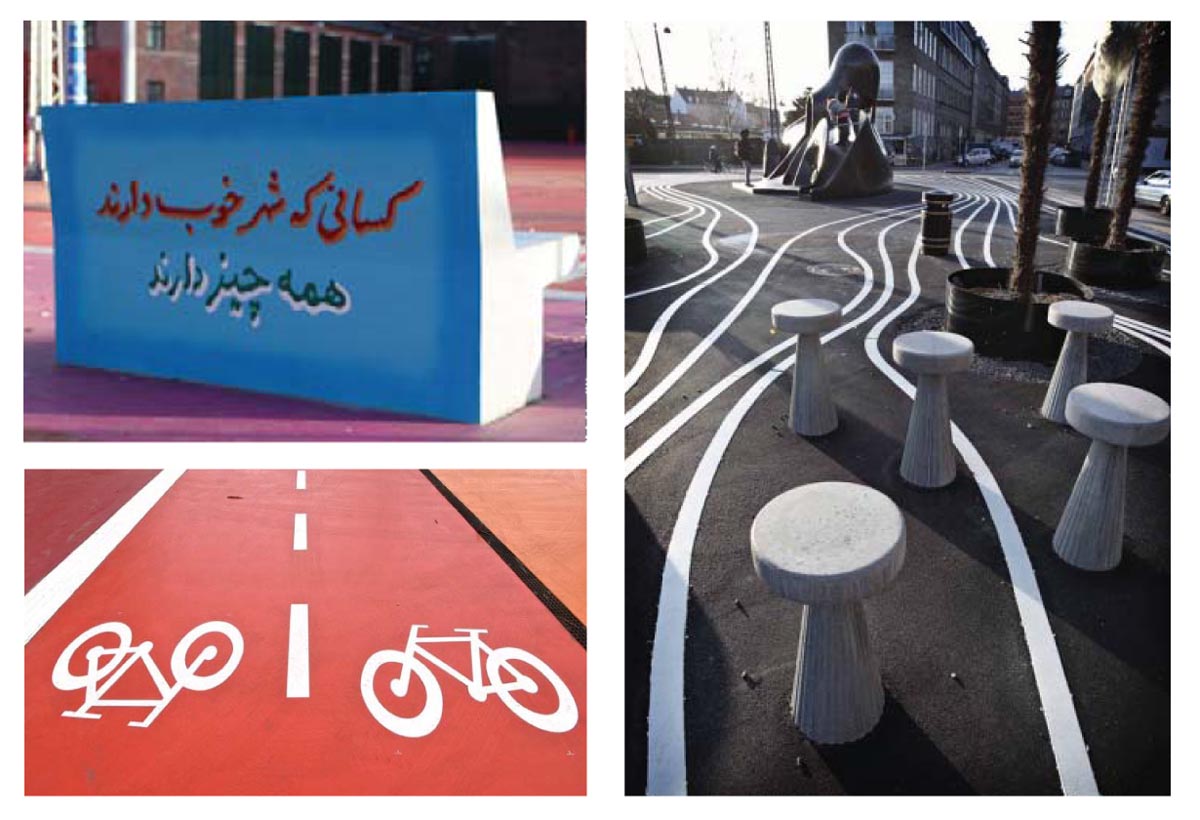

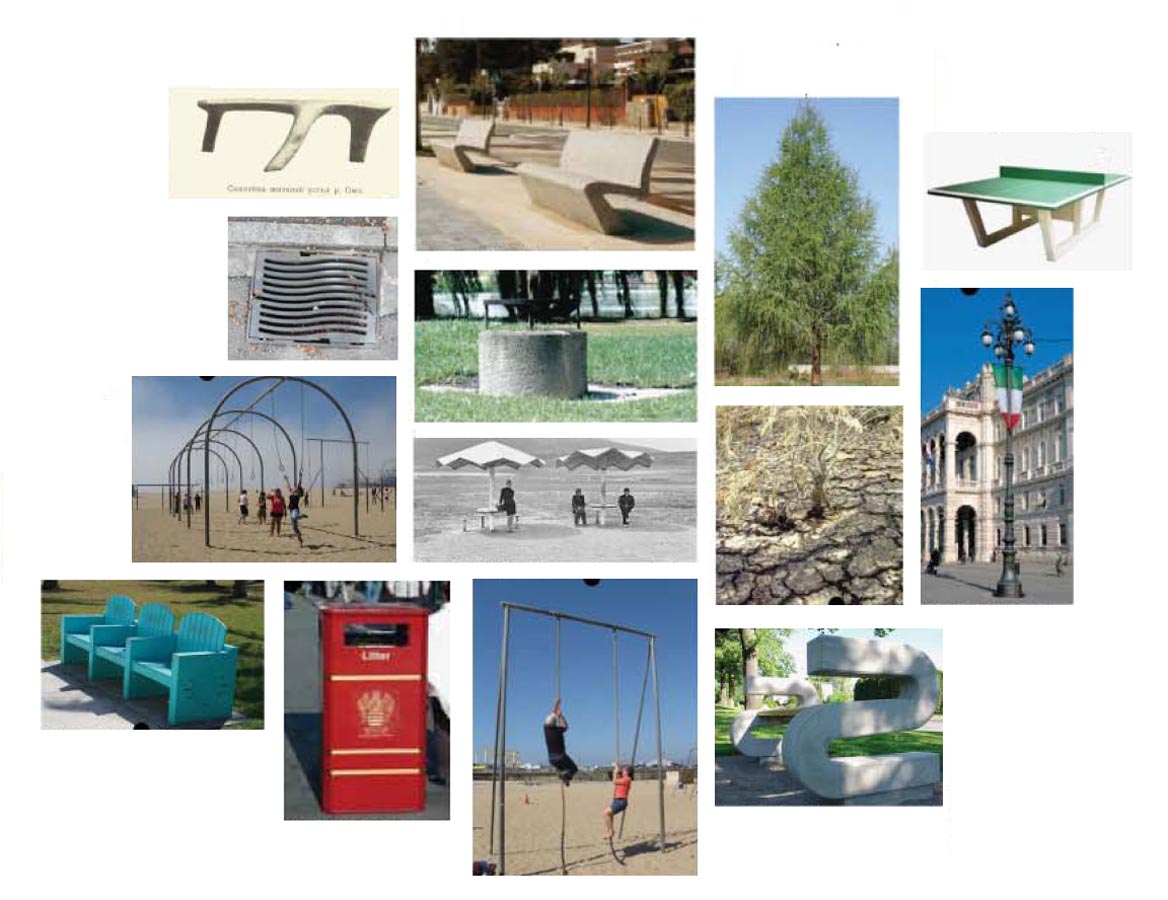

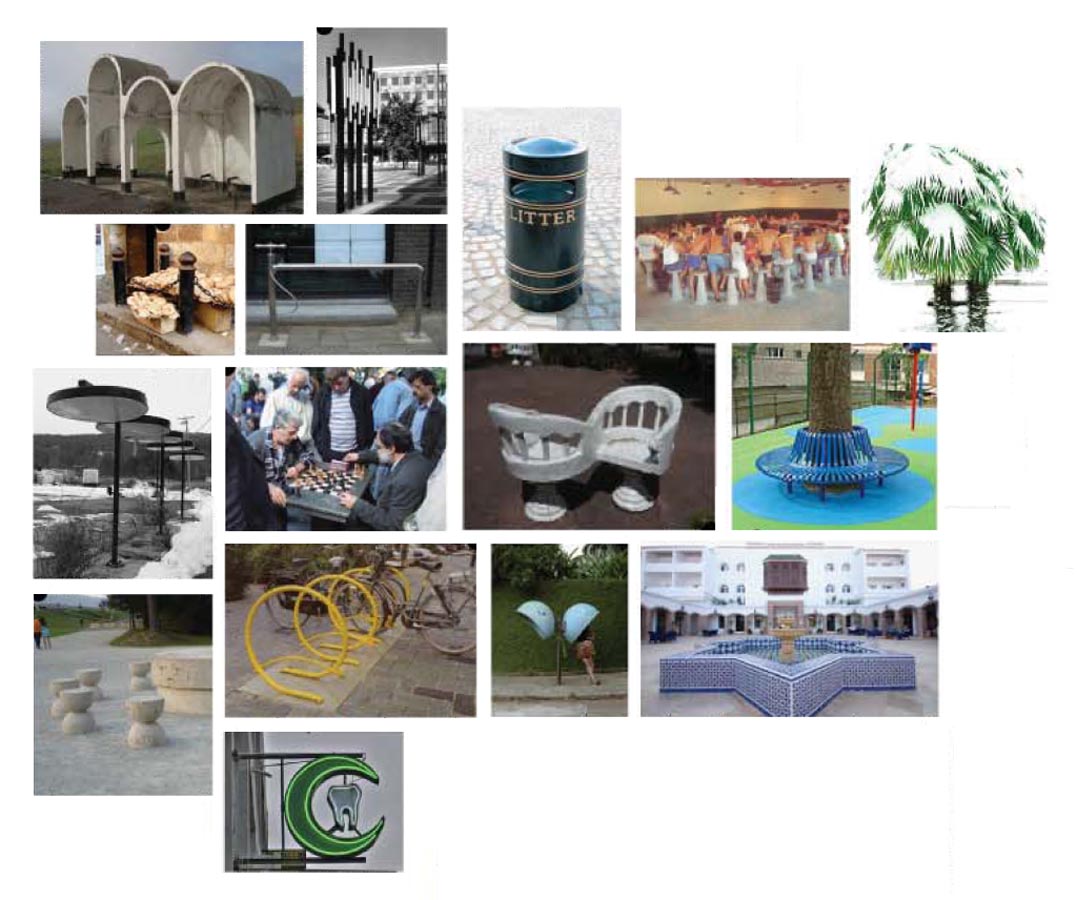

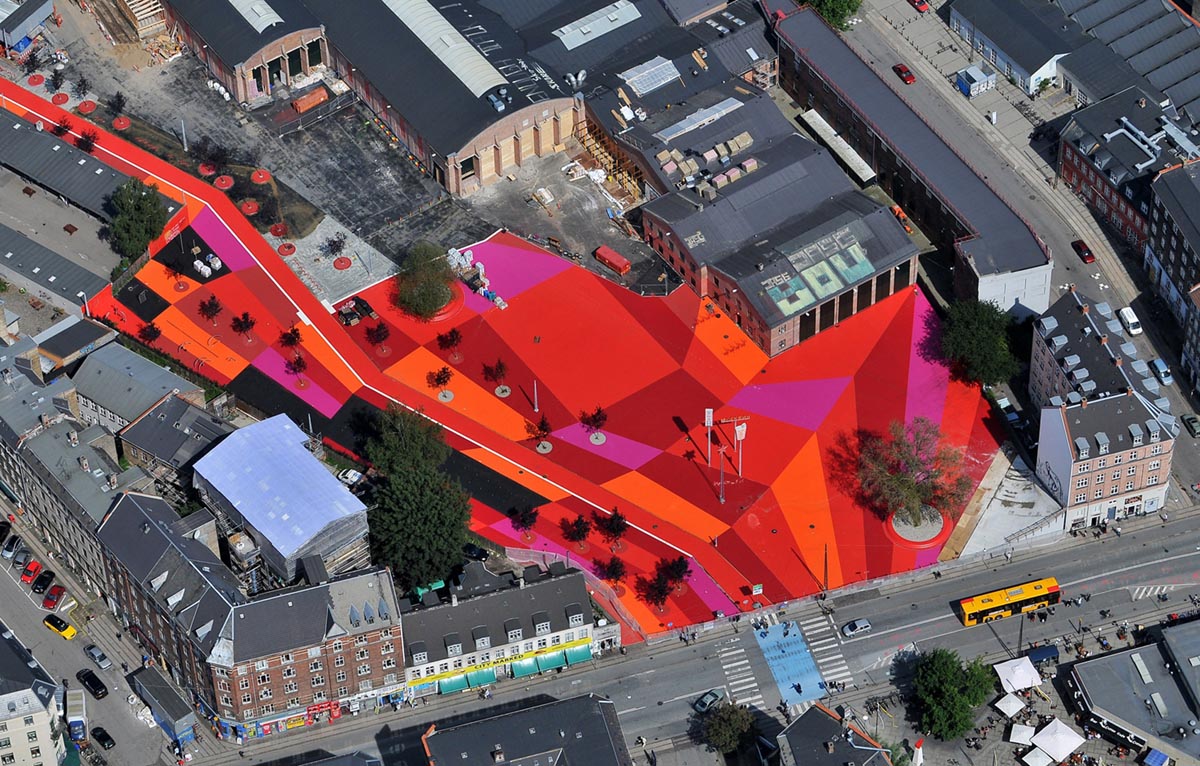

A path for pedestrians and cyclists winds from one end to the other of the park through its three main sections, which are defined by different treatments used on the ground. The southernmost third, adjoining Nørrebrogade Street, is occupied by a “Red Square” covered in an asphalt layer in tones of red, pink and orange. This section is notable for its abundance of artistic installations with cultural references, for example the wall devoted to the Chilean president Salvador Allende, a sound system offering Jamaican music, boards from the red Square in Moscow and neon signs in Russian and Chinese. Trees, including a Japanese cherry and a Norway maple, are scattered here and there among Iranian, Cuban and Swiss benches, several Belisha beacons ─an amber-coloured globe on a black and white pole and typical of some Anglo-Saxon countries─, Thai boxing bags, Indonesian swings, British litter bins, bollards painted with the Ghanaian flag and Irish manhole covers.

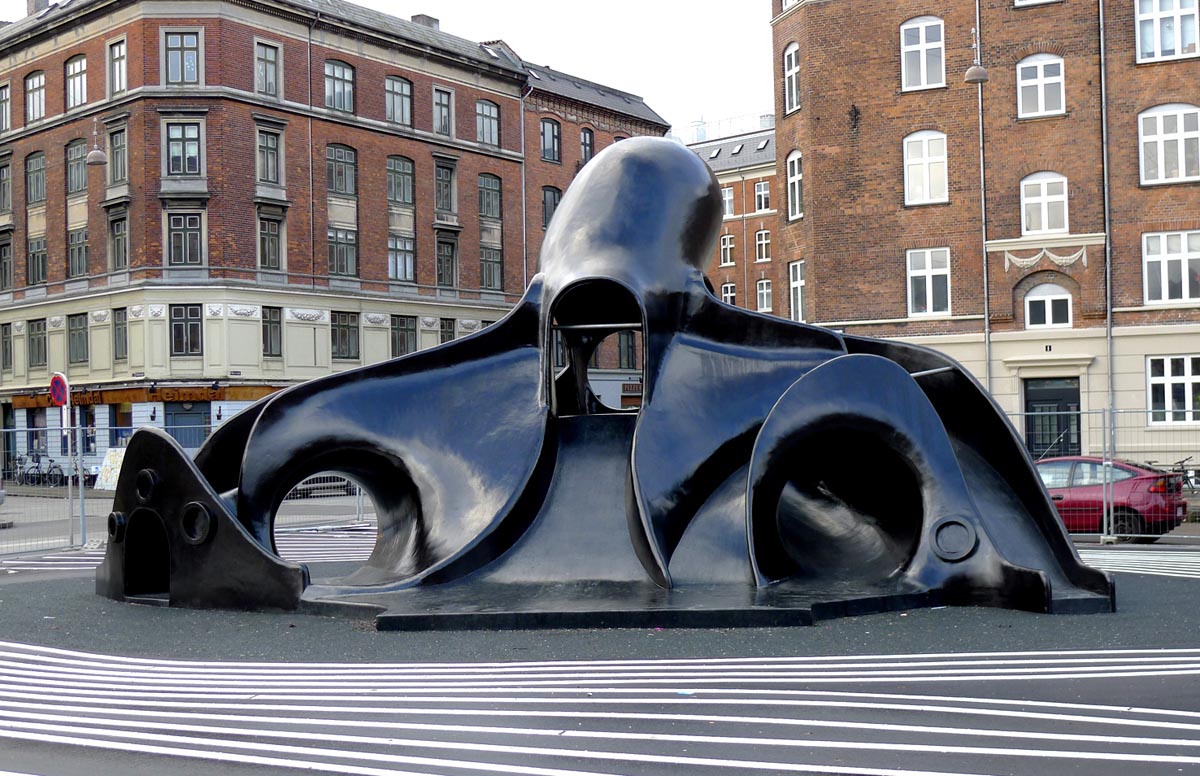

The central part of the park, the “Black Market”, is the smallest and most built-like. The only plants here are a cluster of Chinese windmill palms (Trachycarpus fortunei). This section is also covered with asphalt, now black decorated with sinuous white lines. Its most prominent feature is a large Moroccan fountain, which acts as a meeting point. Another landmark is a Japanese playground slide in the form of a giant calamari. In addition, there are Brazilian phone boxes, Rumanian chess tables, ultraviolet lamps from the United States, Carioca bar stools and a dentist’s sign from Qatar.

The northern and largest part of the park has complied with the residents’ desire for a greener neighbourhood. It extends to Tagensvejdues Street and is called “Green Park”. This whole stretch is green, from the large grassy parterres planted with Lebanese cedar trees and Central European larches, to the zones covered in painted asphalt. Here, benches from Slovenia, Ethiopia, Portugal, Miami, Prague and Porto cohabit with Swiss hammocks, German picnic tables, Kabul swings and Spanish ping-pong tables. A parterre filled with parched soil from Palestine and a typically American three-dimensional donut provide artistic references.

Assessment

“Superkilen” runs ethical and aesthetic risks when it gets close to the frivolity of a theme park concept or to a kitsch mishmash of some kind of bad-taste act of homage. The light-hearted, heterodox and complex-free cheerfulness with which it goes about its project would most probably come from the security arising from the fact that it is all in a good cause. Re-creating distant, exotic places is no novelty in the gardening and landscaping traditions. Here, however, the exotic touches help to bring users closer to homes that are now far away or, depending on the point of view, to make a new home out of the distant place in which they are now living.

The project not only responds to the typical demands of residents openly and without nuances, for example having more green zones or open-air leisure spaces. It also takes their imaginaries as its chief ingredient in moulding them into a sum of different identities in order to create new collective meanings. Instead of perpetuating an image of a homogeneous Denmark, and far from purifying the space with an aseptic and officially approved design, the park, which has been planned so that different kinds of people can enjoy it together, is a cosmopolitan celebration of the richness produced by mixture.

David Bravo │ Translation by Julie Wark

[Last update: 04/07/2022]