Previous state

The Paris banlieue is perhaps one of the settings which most emphatically demonstrates that the claims of modern urban planning are open to question. While prices are rising in the nineteenth-century neighbourhoods of the densely-populated centre because they are deemed desirable, the less privileged sectors of society are piled up in tower blocks in the more recently occupied peripheral zones. Promising democratisation of access to green zones, fresh air and sunlight, these free-standing constructions in fact are a drift in public space which is too big and hence bleak, unsafe and difficult to maintain.Colombes, eight kilometres to the northwest of the Eiffel Tower is no exception to the gloomy rule. Its urban landscape reflects the blight of social exclusion, academic failure, rampant unemployment, xenophobia and criminality. Yet, this municipality of more than eighty thousand residents enjoys a vibrant and solidary associative life. Through a network of more than 450 local associations, civil society is battling marginality with a tenacity and degree of commitment that would be difficult to find in the inner-city neighbourhoods of Paris.

Aim of the intervention

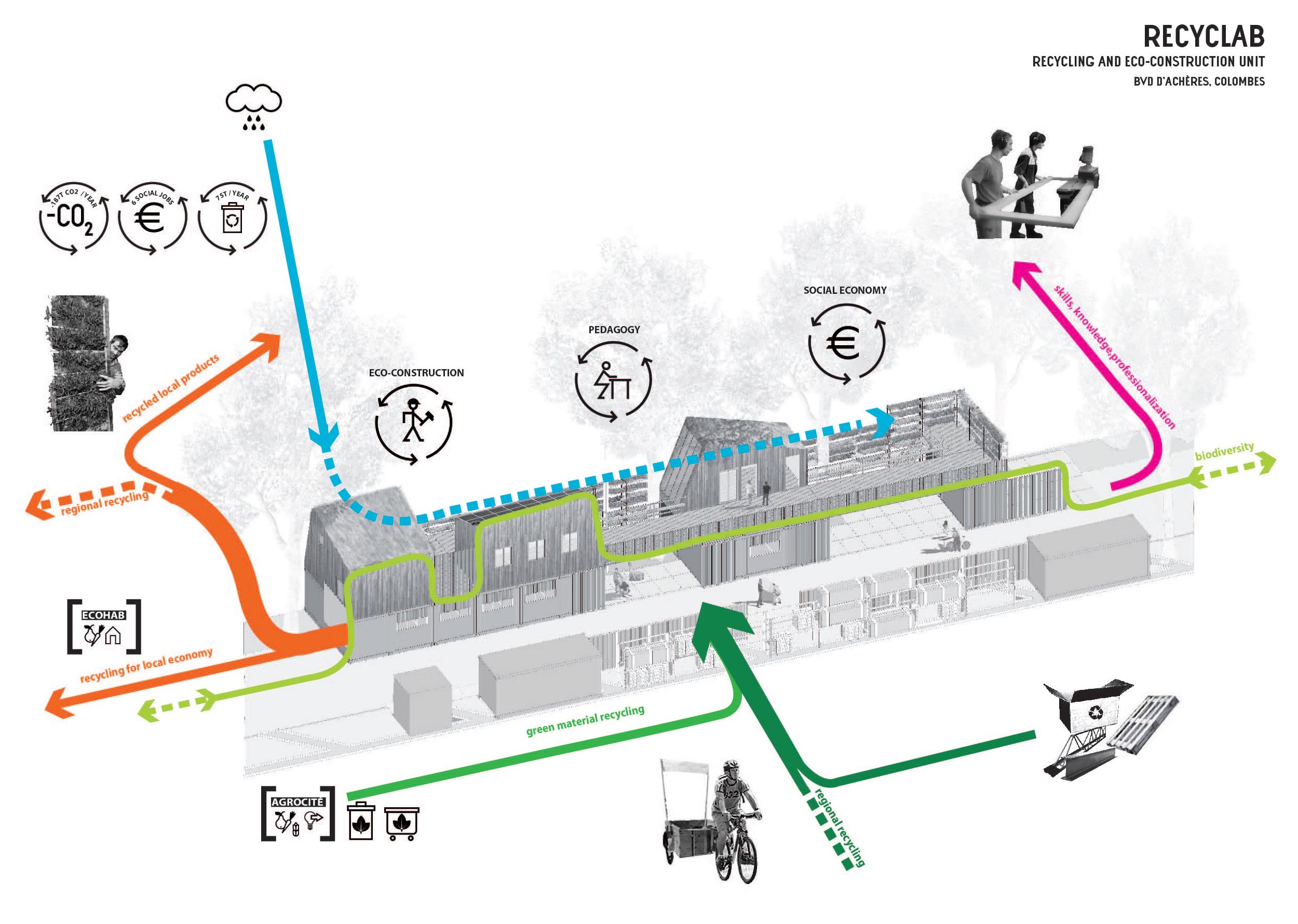

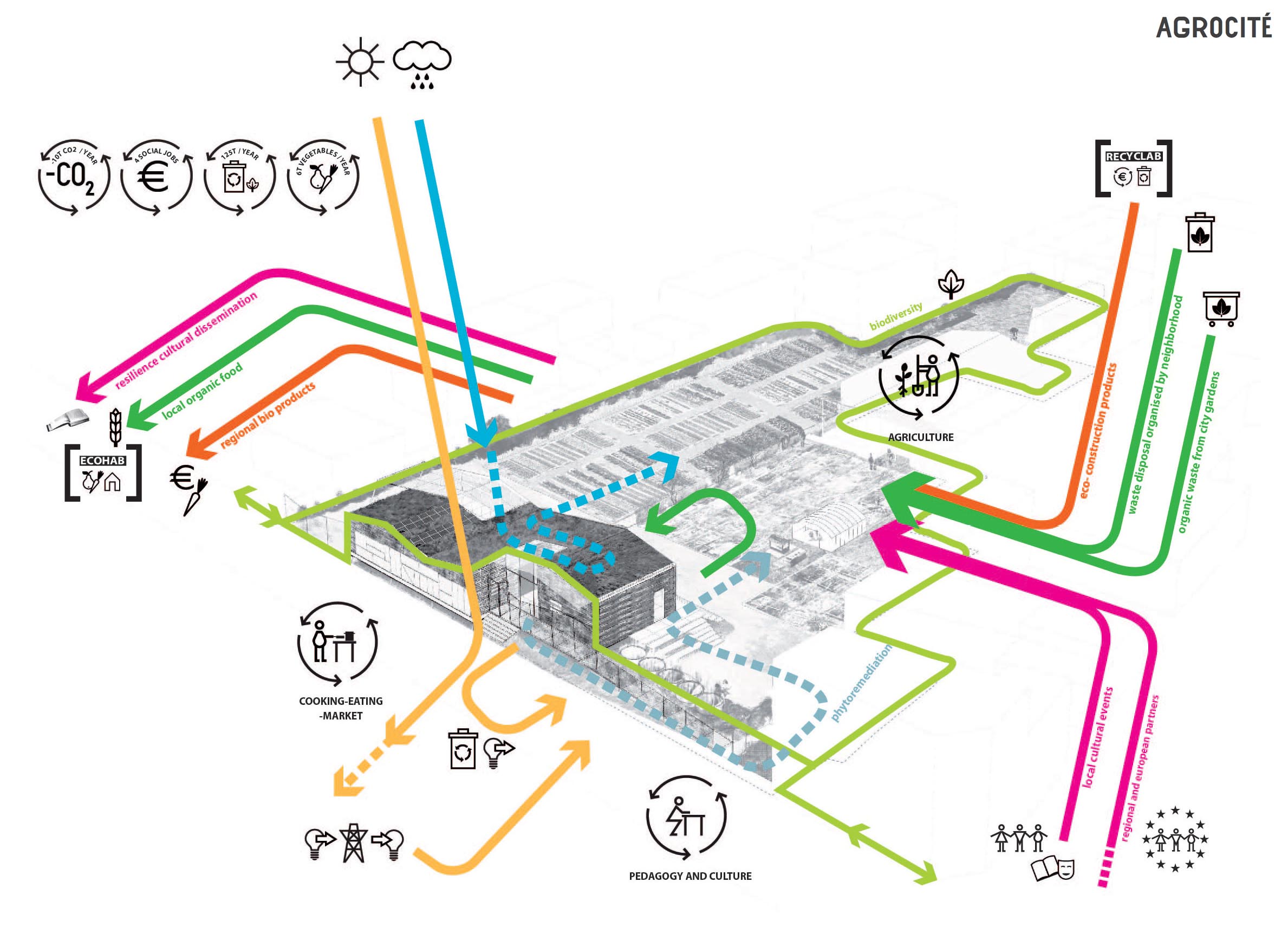

In 2011, a number of these groups organised in order to carry out in spaces ceded by the Colombes Municipal Council a strategy named “R-Urban”. The initiative, which received a European Union grant of one and a half million euros from the LIFE programme for environmental management, planned to create three self-managed community facilities, aiming at the social, economic and ecological transformation of the neighbourhood. One of these, called “Agrocité”, would be devoted to producing ecological crops. Another, “Recyclab”, would recycle recovered materials for sustainable construction, while a third, “Ecohab”, would work to produce accessible, environmentally friendly housing.Description

In 2014, by the time the first phase of the “R-Urban” strategy had been completed, two of the envisaged projects, “Agrocité” and “Recyclab”, were underway. The former is an agricultural hub occupying an area of municipal land of 3,000 square metres in the heart of a housing estate. Most of the land has been used for a food garden, which was planted after the ground had been decontaminated by means of bioremediation, which is to say the use of biological microorganisms to break down and consume pollutants. “Agrocité” is also equipped with experimental devices combining aquaculture —the cultivation of aquatic plants— with hydroponics, whereby plants are grown in nutrient-enriched water without the need for soil. Moreover, a compost plant processing dead leaves and wood from municipal parks contributes seventy-five tons of biomass every year for a generator which produces heating foe the buildings.“Agrocité” has a wooden pavilion with classrooms, a cafeteria, a cooperative store for responsible consumption, a small vegetable market, a greenhouse, and a farm with hives for apiculture. The “Recyclab” is a pavilion of four hundred square metres, also made of wood, which houses storage space for recycled materials and workshops where they are transformed into elements of construction. It is estimated that this centre recycles and reuses about a hundred tons of rubble collected from the surrounding areas. This pavilion also has co-working rooms for designers and local craftspeople which also double as spaces —open to all local residents— for holding repair and restoration workshops, cooperative design and assisted self-construction. Both buildings are revertible because they have been constructed with temporary land-use permits. Accordingly, they are made of reusable components which are easy to dismantle, including containers, woodwork and plank moulding panels. They are equipped with rainwater collection systems and photovoltaic cells for solar power.

Assessment

Unfortunately, the temporary nature of the complex, which was used to justify the takeover of public spaces that were not to be used for construction, has turned out to be its Achilles’ heel. It would seem that the new government installed after municipal elections does not approve of the project and, before the “R-Urban” network could be completed with the construction of the third node “Ecohab”, plans were made to dismantle “Agrocité” in order to make way for a municipal car park. Some local residents have organised demonstrations and petitions in protest at this decision. Meanwhile, the welcoming, human-scale architecture of the two completed pavilions contrasts with the heavy greyness of their environs. Their presence and the greenness of the community gardens have contributed towards breathing life and fertility into two once-barren spaces.However, the improvement which justifies the presence of the complex in the Colombes landscape is not only based on the physical transformation of the urban fabric but, also and especially, activation of the social fabric. Besides the twenty jobs contributed to the municipality with its everyday functioning, the more than five hundred residents who participate every year in the workshops, talks, and assemblies held in this productive, self-managed centre have emerged from frustration and isolation to participate in a shared project. As well as acquiring individual skills, teamwork abilities and ecological awareness, the residents have become citizens who contribute to the co-production of their own neighbourhood. Fortunately, while waiting to see whether the complex will survive or not, other municipalities in the Metropolitan Area of Paris, as Bagneux, Gennevilliers or Montreuil, have shown interest in embracing more nodes of the “R-Urban” network. The “R-Urban Cooperative Society of Collective Interest” is presently being created to this end. This has taken the form of a platform of coordinated associations which wish to extend their model of governance inspired in self-management and solidarity.

David Bravo │ Translation by Julie Wark

[Last update: 18/06/2018]