Estat previ

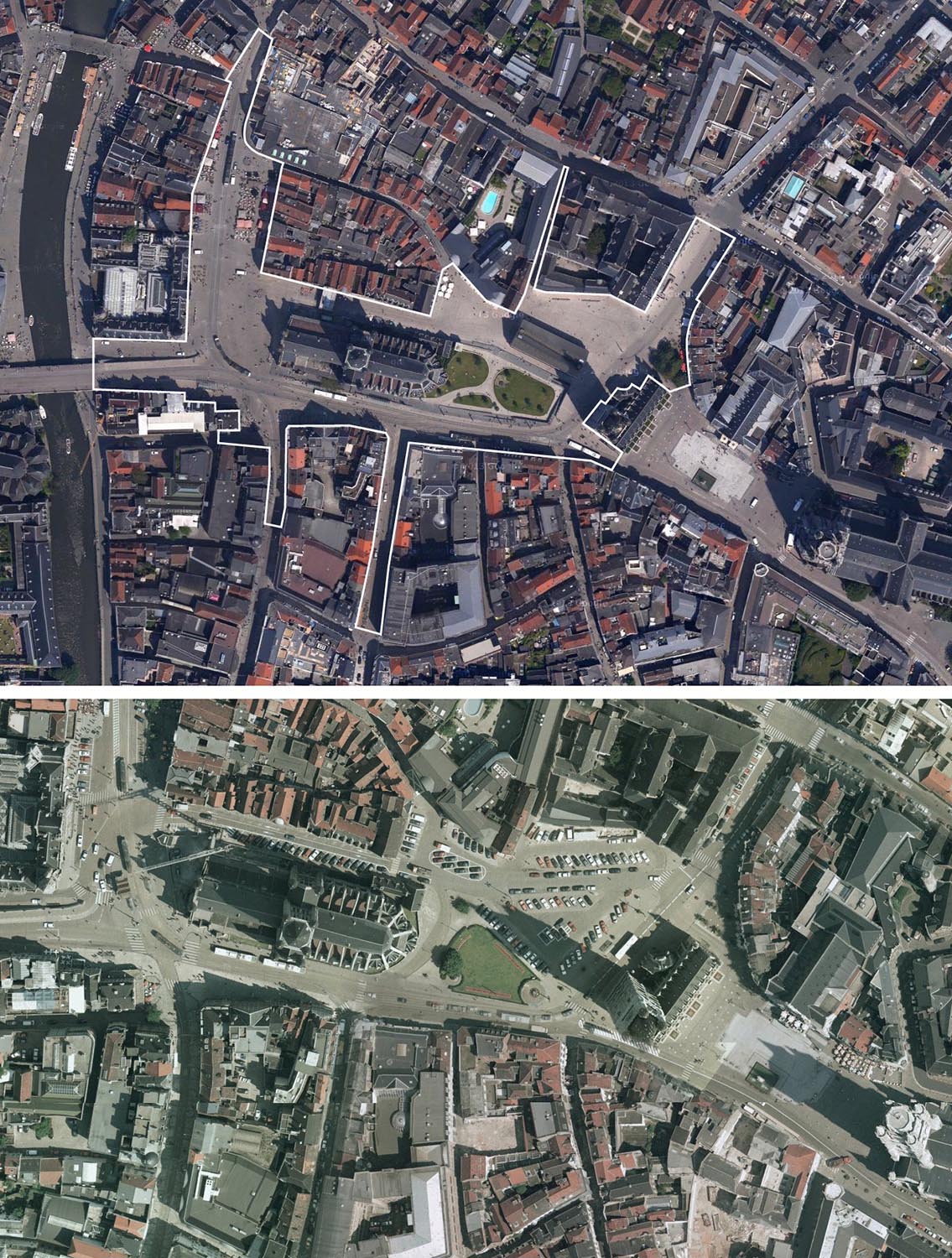

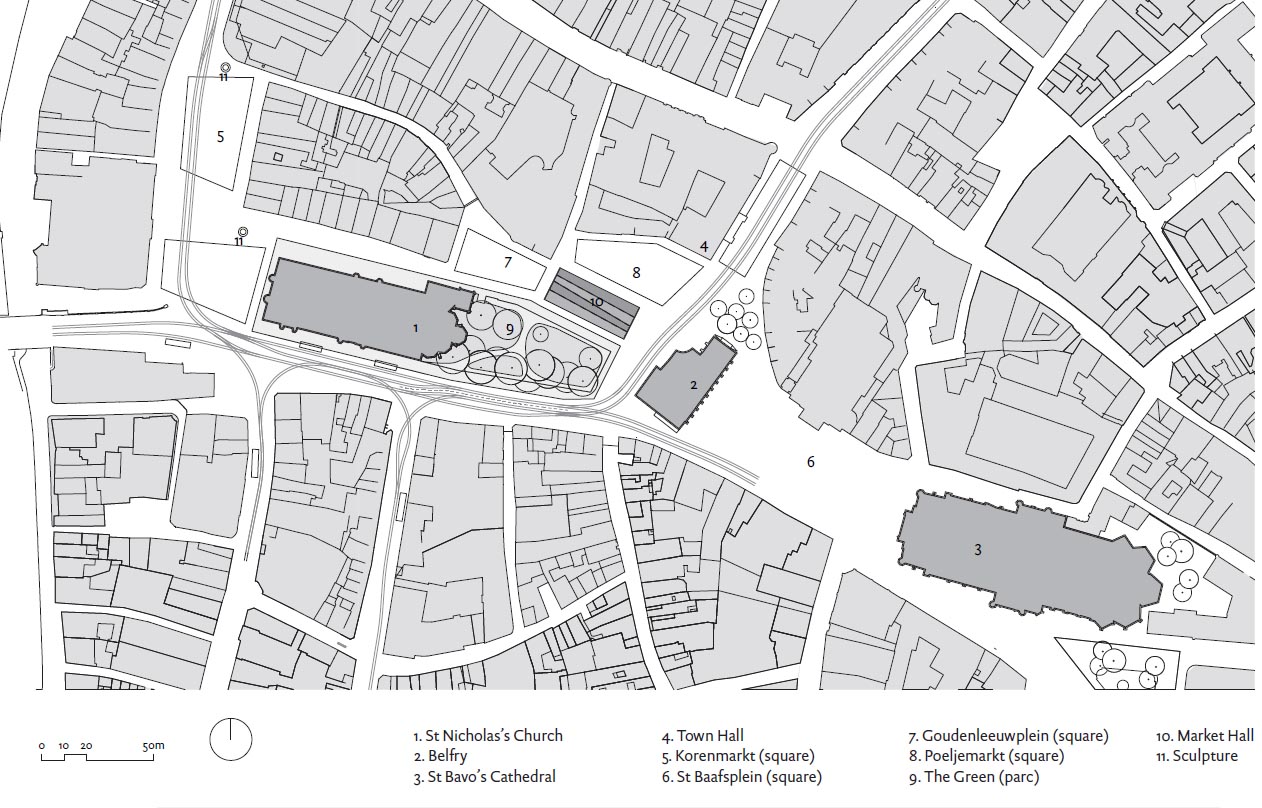

A més de ser l’àrea urbana lliure de cotxes més extensa de tot Bèlgica, el centre històric de Gant destaca per la profusió en arquitectures medievals excepcionalment ben preservades. D’entre elles es distingeixen, per la seva alçada, tres campanars gòtics que donen testimoni de l’esplendor viscuda durant el segle XIV, quan Gant era la segona ciutat més gran d’Europa, només superada per París. Alineades i amb prou feines separades dos-cents metres l’una de l’altra, les tres torres corresponen a l’església de Sant Nicolau, a ponent, la seu de l’Ajuntament, al centre, i la catedral de Sant Bavó, a llevant.Amb motiu de l’Exposició Universal del 1913, el consistori va voler donar èmfasi a la monumentalitat de les tres fites i va emprendre una dràstica campanya d’enderrocs que van obrir noves perspectives alliberant-les d’edificacions adjacents. Els seus volums van quedar exempts, però es va esvair la densitat característica del paisatge medieval que les envoltava. La dilució es va agreujar als anys seixanta, quan es va enderrocar una illa de cases entre la catedral i l’Ajuntament. Les tres placetes que l’envoltaven es van fondre en una sola esplanada massa homogènia i dilatada, bona part de la qual servia com a aparcament en superfície a l’entrada del centre històric. Tot i així, es van mantenir els topònims dels tres buits primigenis, de manera que la placeta d’Emile Braun quedava al sud com una àrea enjardinada i la Poeljemarkt (plaça del Mercat) i la Goudenleeuwplein (plaça del Lleó d’or) a est i oest, respectivament.

Objecte de la intervenció

El 1996, les autoritats municipals van convocar un concurs per reformar l’esplanada i construir-hi un aparcament soterrat. Amb el convenciment que una dotació per al vehicle privat era la darrera cosa que necessitava el centre històric de Gant, un dels equips participants va contradir les bases de la convocatòria proposant un programa alternatiu. Es tractava del «Stadshal», un gran porxo cívic que restituïa el volum de l’illa de cases enderrocada i retornava a les tres places les proporcions perdudes. La proposta va quedar desqualificada, però, un any més tard, va ser la premissa del concurs de construir un aparcament el que seria refusat per la ciutadania en un plebiscit. L’esplanada romandria intacta fins al cap de deu anys, quan l’Ajuntament va convocar un altre concurs per reformar-la. Aquest cop, el projecte del «Stadshal», revisat i complementat amb una proposta de millora del transport públic als voltants, va guanyar la convocatòria.Descripció

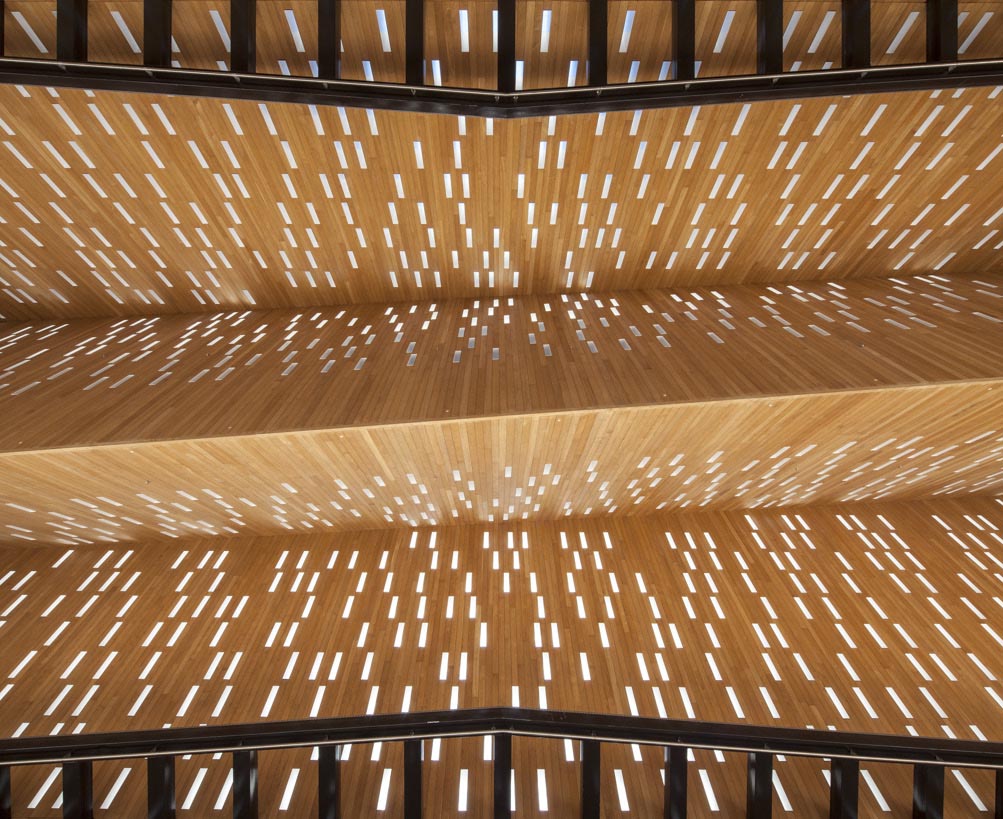

El «Stadshal» és un porxo obert que protegeix els vianants de la pluja i el sol. Eventualment, també serveix d’aixopluc representatiu en concerts, trobades o mercats setmanals. La superfície coberta pel porxo es troba al mateix nivell que la Poeljemarkt i la Goudenleeuwplein i està pavimentada amb les mateixes llambordes. El costat meridional, en canvi, està tancat amb una barana i s’aboca sobre els jardins de la placeta d’Emile Braun, que queda lleugerament enclotada. Aquest canvi de rasant permet il·luminar el semisoterrani, on hi ha serveis públics, un aparcament de bicicletes i una cafeteria.El porxo té quaranta metres de llargada i una alçada intermèdia entre la de l’Ajuntament i la dels edificis propers. Consta d’un parell de cobertes paral•leles, a dues aigües, amb pendents molt pronunciats, com les de les edificacions gòtiques que l’envolten. Estan fetes de panells de fusta recoberts amb teules de vidre i les travessen mil sis-centes lluernes que deixen passar la claror natural del dia mentre que, de nit, converteixen el conjunt en una gran llanterna que emet llum cap a l’exterior. Les dues cobertes reposen sobre quatre grans nuclis de formigó situats a les cantonades. Dos d’ells contenen xemeneies que permeten encendre grans llars de foc al nivell de la plaça. Als altres dos hi ha ascensors i escales que porten al semisoterrani.

Valoració

Els setze anys que van transcórrer des que la proposta del porxo va ser desqualificada fins a la seva inauguració no han estat exempts de controvèrsies entre representants polítics, ciutadans, arquitectes i mitjans de comunicació. No va ser fàcil per a tothom acceptar la irrupció d’una peça arquitectònica amb un llenguatge tan rabiosament contemporani en un lloc tan carregat de sentit històric. A més, la decisió de retirar els cotxes de l’esplanada sense oferir com a alternativa el nou aparcament soterrat no va plaure a tothom.En tot cas, el valor del «Stadshal» és molt més evident al carrer que sobre el paper. Sense caure en el mimetisme o la submissió, la contemporaneïtat de la seva forma manté amb el context històric un diàleg respectuós però suggeridor. En efecte, les cobertes inclinades del porxo s’adiuen amb les veïnes sense pretendre confondre-s’hi. A més, la presència del «Stadshal» contribueix a revertir els excessius esponjaments que va patir la part vella de Gant. El seu volum densifica un teixit on els espais buits sempre havien estat intensos perquè escassejaven. Més enllà de les formes, la intensitat del carrer també surt reforçada amb l’aposta per la bicicleta o el transport públic com a sistemes de mobilitat molt més adients per a un centre històric. En definitiva, la intervenció entén l’espai públic com quelcom més que un lloc de pas o un mer aparcament i convida la gent a quedar-s’hi i sentir-s’hi com a casa a través d’elements ben propis del refugi domèstic, com són el sostre o la llar de foc.

David Bravo

[Darrera actualització: 05/09/2024]