Previous state

Like many other European cities, Copenhagen underwent a process of deindustrialisation in the last quarter of the twentieth century. The port, one of the most important in the Baltic Sea, gradually divested itself of its heavy and manufacturing industry installations in order to specialise in container transport and cruises. Hence, abandoned factory infrastructure and installations came to be a predominant feature in the port setting that had traditionally nourished the city’s public, productive and commercial life.New tertiary-sector companies have begun to repopulate the run-down landscape with office buildings, clean industries and shopping centres. However, these premises have often been put up quickly, without much forethought, and tend to be too inward looking. In such a swift transformation there has been no time for quality public spaces to take shape. Constructed with cars in mind, the new port is not an inviting area, and it also presents many difficulties for pedestrians and cyclists who may wish to circulate there.

Aim of the intervention

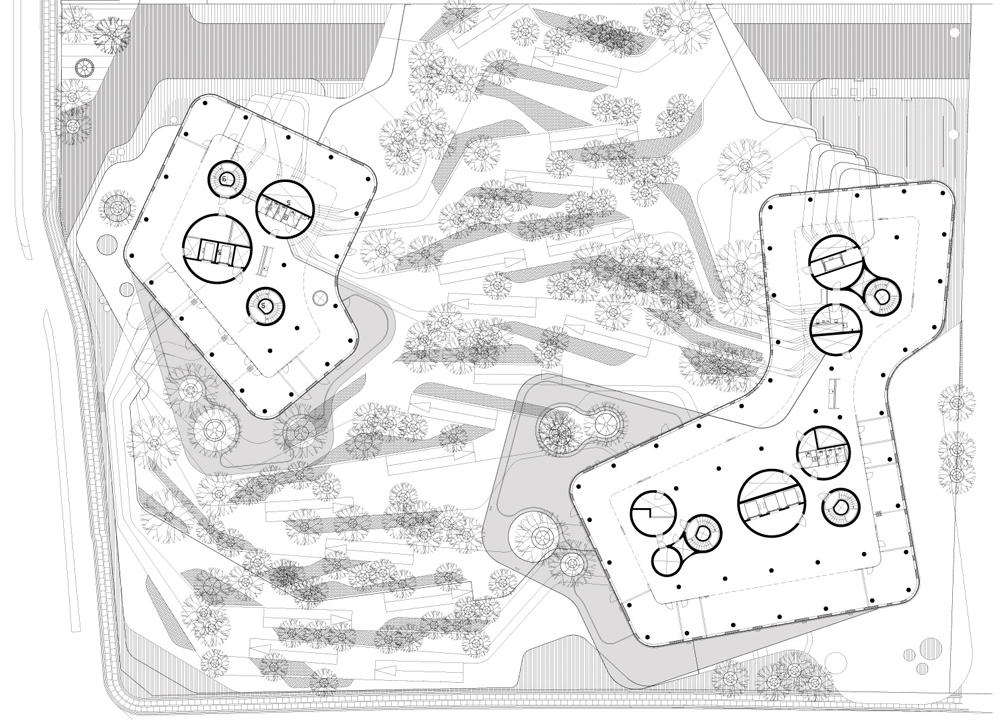

In 2005, a Swedish bank decided to establish its Danish headquarters on the northern shore of the port, next to the post office and the Copenhagen Central Station. The architectural project envisaged two free-standing towers, each one of some ten storeys, on a more-or-less square corner plot that had once been used as an open-air parking lot. The positioning of the towers freed a good part of the more than seven thousand square metres of land they occupy and it was decided that, although this was private property, the residual space would be opened up to the city. By making a contribution towards improving the quality of urban space in the new port zone, the bank was seeking to enhance its corporate image. With this aim in mind, it offered Copenhagen a new garden called “Bymilen” (Urban Dune), which was designed as a fully accessible hillock of uneven contours respecting the values of sustainability.Description

The “Urban Dune” consists of a serpentine series of white concrete plaques, terraced at different levels and interspersed with green strips where trees and bushes are planted. The whole area, covering an underground car park, rises up to seven metres above the level of the streets around its perimeter and offers different leisure-time areas for bank workers and visitors. The paved paths are adapted for people with reduced mobility. All the surfaces drain into two large underground tanks, which store rainwater to be used for irrigating the planted areas. The tanks also supply water for a hundred and ten atomisers that produce clouds of vapour to cool the atmosphere in the hottest part of summer.Assessment

When the “Urban Dune” is presented as a statement in favour of the democratisation and sustainability of public spaces, it is quite likely to arouse suspicion. First, the fact that the space is private property owned precisely by a finance corporation does not make it easy to accept that it has great affinity with the notions of either “public” or democracy. Moreover, the contention that this garden ─so full of concrete and, indeed, the roof of a car park─ has an ecological mission is not very plausible.For all that, nobody can say that ─like the other tertiary sector areas in the new port─ this space is inward-looking or that it has been cobbled together in a hurry. Whether it is democratic and sustainable or not, it is a pleasant, accessible garden where office workers can enjoy a break and where people meeting informally in the open air mingle with strolling pensioners, and adolescents who make good use of its quirky geometry for skateboarding. Moreover, if the fact of its providing a space for different kinds of people to enjoy weren’t sufficient, its goal of improving the landscape in the inhospitable urban context in which it is set must also be emphasised. This aspiration is a reminder of the extent to which private spaces come to determine the quality of the public space they demarcate.

David Bravo Bordas, architect

[Last update: 02/05/2018]