Previous state

On the Adriatic coast of the Dalmatia region, the city of Zadar is familiarly known to its inhabitants as the 'stone vessel' because it occupies a small elongated peninsula. During the Second World War the city became the headquarters of a German garrison and was bombed seventy-two times by British and American planes.

When the war ended the chaotic reconstruction of the city resolved the north-western seafront of the peninsula, the prow of the ‘stone vessel', with an indifferent concrete wall that did not correct its neglected state. In spite of the superb sunset over the Adriatic Sea–described by Alfred Hitchcock as ‘the most beautiful in the world’–the spot was hardly visited by the citizens of Zadar.

Aim of the intervention

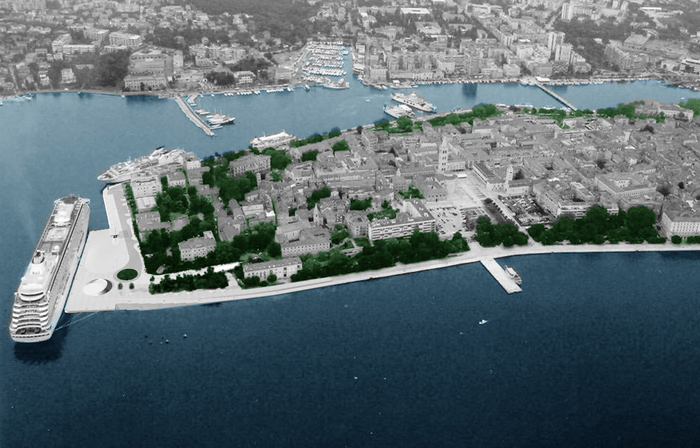

In 2004, given the incipient tourist activity in Croatia, the Zadar Port Authority, with the support of the Municipal Government, decided to undertake the reconstruction of that segment of the seafront and equip it as an arrival jetty for the cruise ships. And so the 'stone vessel' would be rescued from negligent municipal oblivion and become the gateway to the city.

This new arrival point made clear the need for a marine parade that would resolve the route to the city. But the place would not have a merely vestibular function, exclusively aimed at receiving tourists; the citizens of Zadar had to definitively make it theirs.

Description

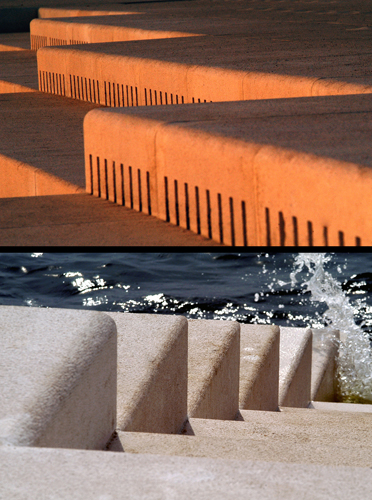

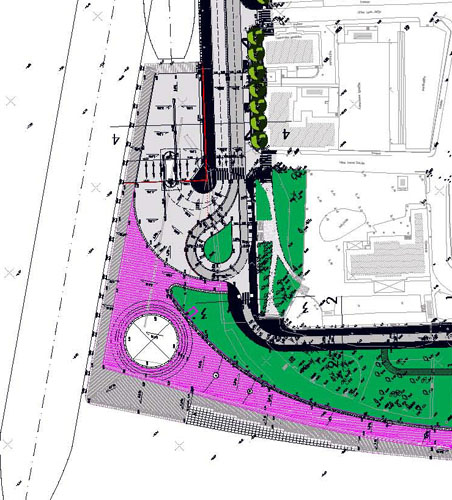

Finished in 2005, the new arrival jetty for the cruise ships occupies the far north-western tip of the peninsula with a large corner platform where the marine parade that follows the south-western shore begins. It is at the confluence of the platform and the parade that the sea organ extends along a seventy metre front. The solution adopted consists of resolving the meeting with the water gradually, by means of a flight of broad white marble steps that go down beneath the waves.

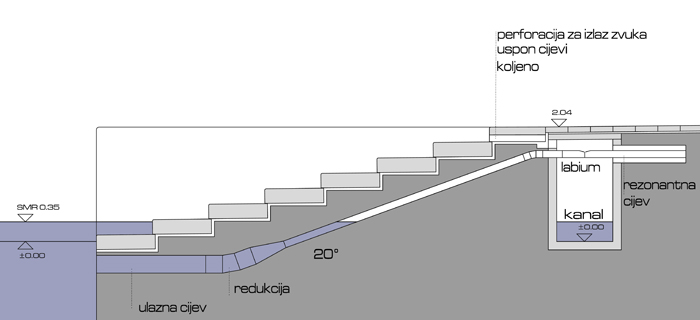

The steps are made up of seven parallel flights, each one ten metres wide. The seven flights are juxtaposed in such a way that at each change of flight there is a difference of one step; that means that the steps both at the junction with the parade and at the water's edge the flights present a staggered silhouette. The first three are the longest; they consist of six steps and descend about two metres, which is the highest level of the cruise ship arrival platform. From the fourth flight, the height of the parade gently approaches the water level, so that each new flight loses one step. The last flight, which has reached the definitive level of the parade, has only two steps above the water.

But the proper adaptation to the topography of the parade is not the only explanation for the variations in the dimensions of the flights of steps. There is another which establishes a clear formal analogy with the variations in dimension and arrangement of the parts of a musical instrument. A series of polyethylene tubes of different diameters run along the inside surface of each flight of steps, connecting the submerged part with a gallery that runs along beneath the parade. With the variable force of the waves, the water penetrates the lower end of the tubes and is carried into the subterranean gallery, which collects it and returns it to the sea. In this process the air of the interior of the conduits is pushed to orifices that connect the gallery with the surface of the parade, generating sound vibrations which, given the variations in the diameter and length of the tubes, cover a broad range of musical tones.

Assessment

Despite the existence of a previous sea organ, built in 1986 in San Francisco Bay by Peter Richards, the Zadar sea organ excels for its formal simplicity. Avoiding the abruptness of the common jetty, understood as a rectilinear platform elevated above the water level, the Zadar steps allow the dissolution of the border between land and water and preserve a dilated transit space between the two. In that way the jetty is no longer an unexpected barrier that protects but distances man from the sea; it summons, like a beach, the coming and going of the waves. The section of the flight of steps makes it a perfect grandstand for watching the sunset over the sea and the outline of the neighbouring island of Ugljan, while listening to the musical compositions played by the sea itself. Inevitably these two great attractions have not passed unnoticed by the citizens of Zadar, who have now really appropriated this public space with general devotion.

David Bravo Bordas, architect

[Last update: 05/09/2024]