Previous state

Reality undermined the expansion plan designed by the engineer and hygienist Ildefons Cerdà for Barcelona in 1860 when the city walls were demolished. Despite the radical nature of his utopian proposal which, by means of its gridiron design, promised to democratise access to sunlight fresh air and vegetation, pressure from landowners and speculators ended up producing a substantially denser city than what was planned in the project, and a great number of spaces originally envisaged as green zones were used for construction. This undermining of Cerdà’s plan shaped Barcelona as one of Europe’s most compact cities which, paradoxically, has had very positive effects in terms of equitable, sustainable mobility since it allows the city to have a public transport network which stands out very favourably—also in terms of pricing—when compared with good systems in other European cities.

However, this compactness is deadly when too many licences are conceded to private vehicles. Barcelona today has a density of 7,000 vehicles per square kilometre—by comparison with 3,000 in Madrid, 1,500 in Paris, and 1,200 in London—which has dire effects on spatial justice and health. More than 60% of public space is given over to cars, even though they are only used for 20% of movements around the city, and the average occupation per vehicle is just 1.2 people. Every year, more than 700 people die prematurely because of air pollution which, well above the limits set by the WHO, makes Barcelona the second most contaminated large city in the European Union.

Aim of the intervention

For more than thirty years, different municipal governments have seen the “superblock”—an old concept of modern urban planning for freeing certain urban sectors from fast-moving traffic—as a structural solution to the problem. Over these years, the city has successfully applied the model in several historic nuclei of the most densely populated part of the city. Nevertheless, systematic application in the zone planned by Cerdà, an extension of more than seventeen square kilometres consisting of nearly a thousand square blocks of 113 metres each side and with streets twenty metres wide, was not seriously considered until the Urban Mobility Plan (2013-2018) was approved. One of the chief aims of this plan is to reduce the space occupied by the private vehicle so as to favour surface to be used by pedestrians, and to introduce a series of bicycle lanes, as well as an orthogonal network of fast bus lanes. These networks define some sectors where cars can continue circulating normally and large interstitial pedestrian areas where they can only move in a more restricted, slower, and more respectful fashion. With the “Superblocks Programme 2016-2019”, the City Council identified several areas in the Cerdà Plan zone that are to be successively pedestrianised. The first of these, designated the “Poblenou Superblock” is located in the Poblenou neighbourhood, of the Sant Martí district, a former industrial zone which, less densely populated than the rest of the grid, offered the terrain which seemed most suitable for a first pilot project.

Description

The “Poblenou Superblock” is an area of four hundred square metres, delineated by Badajoz, Pallars, La Llacuna and Tànger streets. It is comprised by what would be nine archetypical blocks of Cerdà’s design if not for the fact that three of them are crossed at an angle by carrer de Pere IV. The inner streets of the “superblock”, which are twenty metres wide, previously allowed five metres either side for footpaths and ten metres of road—three lanes and parking space—for cars. After the intervention, motorised traffic has only one lane and is obliged to make a ninety-degree turn at each crossroads. This means that, in each street section, 75% of the surface, once occupied by cars, has been freed and, at each crossroads, typically with 45º chamfered corners, the surface gained is 2,000 square metres. The plan allows guaranteed access for vehicles to all the buildings within the pedestrianised zone but they will be obliged to move more slowly and taking a more roundabout route.

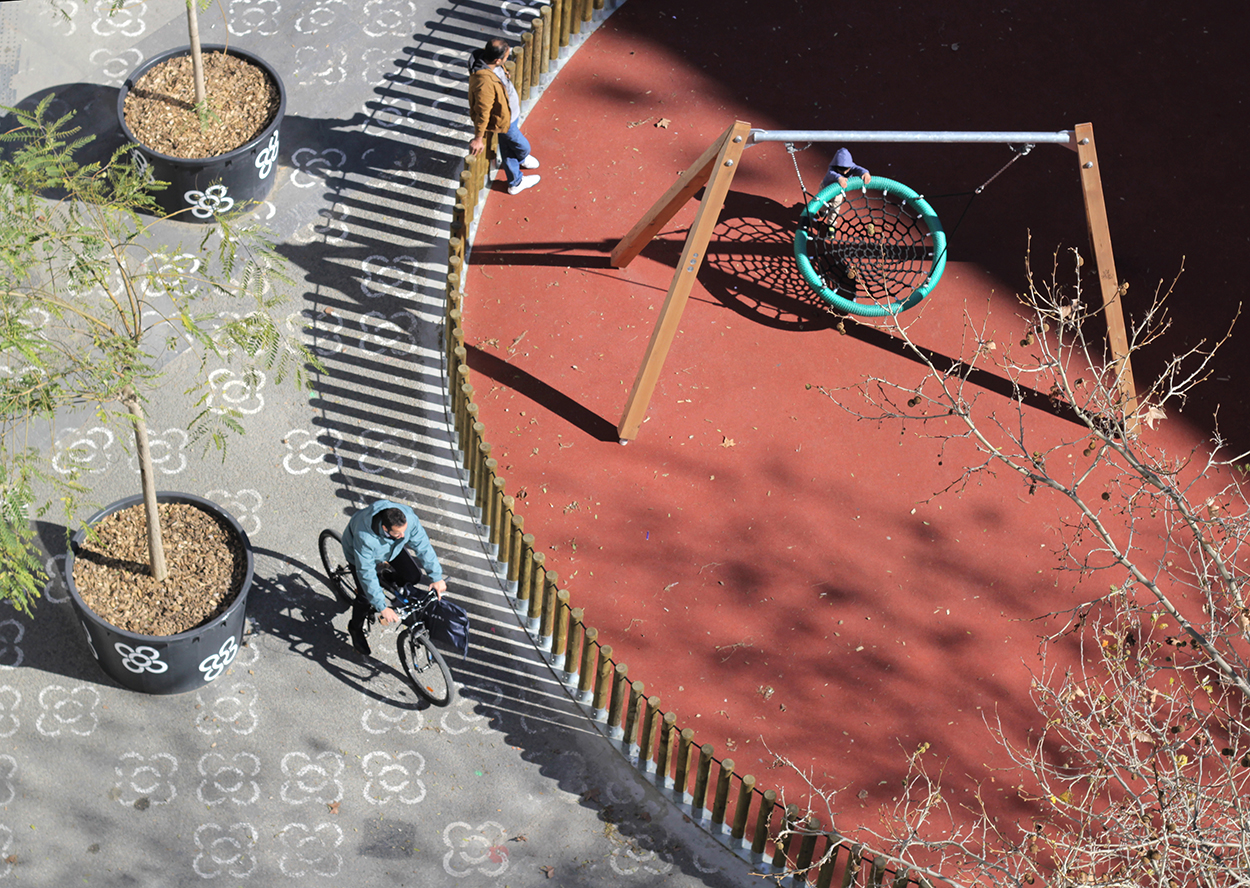

This change in the distribution of public space has been carried out in two successive stages. The first has been implemented on the basis of “tactical urbanism” solutions, conceived by students at several schools of architecture, for example the reversible application of signs painted on the ground, the temporary installation of elements of street furniture, and placement of trees planted in mobile containers. The provisional nature of these solutions has speeded up the work of introducing the changes and has cut expenditures to one tenth of what a conventional project would have cost. However, more than anything else, it has enabled the introduction of modifications in accordance with results of a participative process with local residents. These have given rise to children’s playgrounds, sports areas, picnic and ping-pong tables, meeting spaces, literary tours and temporary markets. Now that the spaces have been empirically and pedagogically submitted to a series of trials assessing uses, the second phase, initiated in autumn 2017, has consisted in consolidating the intervention on a permanent basis by means of conventional civil engineering work.

Assessment

Thirty years before the car was invented, Ildefons Cerdà predicted that Barcelona residents would move in “private locomotives”. What this visionary engineer did not foresee was that the congestion caused by these lethal machines would jeopardise his hygienist’s vision of a greener, healthier city. After a century and a half, the strategy of extending “superblocks” the length and breadth of his gridiron plan promises to revive his dream. In total, the “Poblenou Superblock” has increased public space for pedestrians by 13,350 square metres. Although traffic in the four roads around the perimeter has increased by 2.6%, the number of vehicles circulating in the inner streets has dropped by 58%. In these streets which once exceeded the WHO’s noise exposure limits, daytime noise levels have dropped by an average of five decibels. More than three hundred benches have been installed, 212 new trees planted, and open-air cultural activities have multiplied.

However, the Poblenou pilot project has confirmed that despite abundant scientific evidence demonstrating the pernicious effects of cars in cities, the population is not yet fully aware of this. A few days after the first phase was implemented, a media storm was whipped up. This was an unprecedented phenomenon in Barcelona’s urban planning in recent decades. A not inconsiderable number of local residents and businesspeople started a wave of continuous vociferous protests in not a few branches of the media despite the fact that many residents working in nearby offices and children attending the public school had soon demonstrated that, with cars removed from the streets, a magical renaissance of urban life has taken place. All in all, it would seem that the battle to pedestrianise the streets of Cerdà’s grid will be long and tough. In any case, the controversy should not necessarily be read as a failure which diminishes the value of the intervention. More than a conventional urban regeneration project, the “Poblenou Superblock” can be understood as a cultural product which has brought to light the need to make a commitment to more equitable and sustainable mobility as a way of combatting such serious but often overlooked emergencies as spatial injustice, poor air quality, and climate change. In this regard, the first pilot trial has helped to pave the way to the next “superblocks” in the Barcelona of the Cerdà plan.

David Bravo

PUBLIC SPACE / Poblenou “Superblock” (Barcelona). Special Mention. European Prize for Urban Public Space 2018. (Enlish with Catalan Subtitles) from CCCB

[Last update: 19/05/2023]